Meet the winner of our #PublicLandsPup photo contest and learn what her family loves about hunting and fishing on public lands

We’re excited to announce the winner of our #PublicLandsPup photo contest: Allison Carolan and her Labrador retriever Beau!

With hundreds of photo submissions to choose from, you guys didn’t make it easy for us to pick just one winner. But this lucky pup will receive a new dog bed from Orvis to rest up for her next public-lands adventure.

We talked with the winning #publiclandsproud photographer, Allison Carolan, and asked her to tell us more about the photo, her dog, and what public lands mean to both of them.

TRCP: Congrats on winning the #publiclandspup contest, Alli! Where were you when you took this amazing photo?

CAROLAN: I took this photo in December in the Nemadji River bottoms on public land near Wrenshall, Minnesota. My husband, Andrew, and our 7-year-old Labrador retriever, Beau, and I were looking for grouse at the time, and we had just walked some single tracks for an hour or so before pausing to take in the sunrise over the Nemadji River valley.

It was about three degrees that morning, and everything was covered with hoarfrost in the valley. The frost was so heavy that some of the crystals were blowing off the trees and shimmering in the air in a crazy, otherworldly sort of way. We stopped to stare at the scene and didn’t even care that we hadn’t flushed a single bird yet. It was actually so cold that some of my breath distorted the light just slightly in the photo.

TRCP: It made for a truly amazing shot. How does Beau like to enjoy public lands?

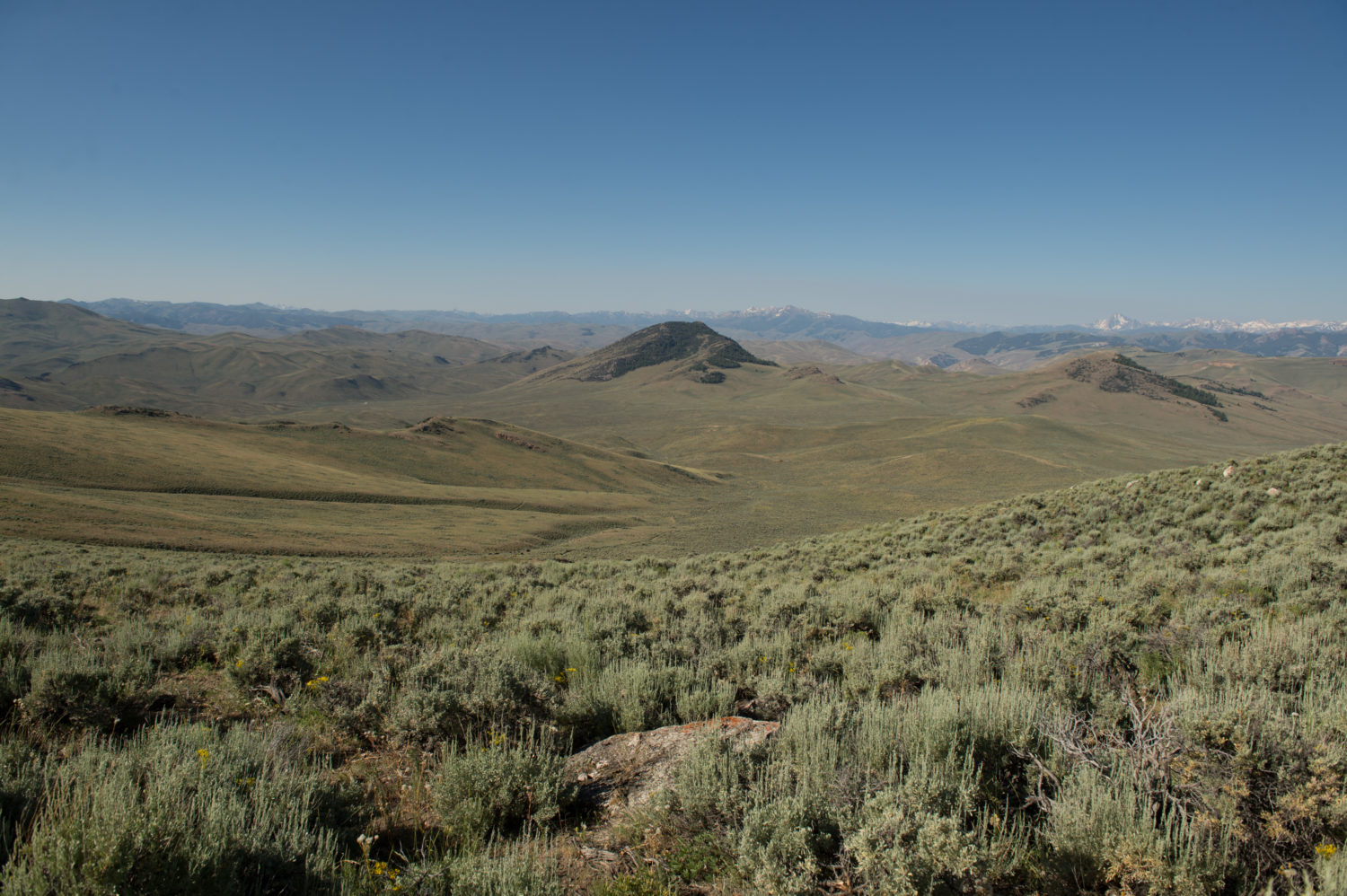

CAROLAN: Beau loves to hunt, especially pheasants, Hungarian partridge, and sharptails. She specializes in long, challenging retrieves on the big grasslands of western Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and central Montana. In fact, at this very moment, Beau is with my husband at a base-camp on public land outside of Lewiston, Mont., on the Pheasants Forever Rooster Road Trip. (You can follow along with the adventure here.)

Beau is a wild bird snob, loves an authentic hunting experience, and we really only take her to hunt on public lands. You can tell she loves the challenge of flushing late-season roosters that are holding tight in thick cover, the ones that other dogs might have missed.

TRCP: What about you? What attracts you to our public lands?

CAROLAN: As for me, I just completed my hunter safety course, but haven’t completed my field day training yet. For now, I’m content to walk along, watch Beau work, take photos, and contribute to the wild game dinners afterward. I am, however, an extreme frequenter of public lands. I’m an ultra-marathon runner and wilderness canoeist, so I spend the vast majority of my free time seeking out and training on all kinds of public lands. I’ve run on the backcountry ATV trails of western Montana, in countless national parks and forests, and around portage trails in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. In general, the wilder the place, the more I like it. Since I cover a lot of ground in my training, I’m a decent scout for everything from morel mushrooms to rare plants to birdy-looking areas. I sneak up on a lot of grouse during trail runs and take note of good future hunting locations when I find them.

I also grew up trout fishing in the Driftless Area of northeast Iowa and have spent many hours fishing on public lands in that region and out West.

TRCP: Knowing all this, it seems like Beau truly is a #publiclandspup and well deserving of a new bed from Orvis.

CAROLAN: For sure! Beau will absolutely love the new Orvis bed, and I’ll be putting it in her favorite place in the house—right in front of the fireplace. I’m sure she’ll appreciate it after putting in some hard work this week.

Below are some of our other favorite #PublicLandPup captures shared with us during the campaign.

Labs rock! Pheasant hunting behind my lab is heaven on earth.

State pubic lands not federal should be the rule.

Where in the Constitution does it discuss our Federal government holding vast amounts of land? It doesn’t.

Lands within a state should belong to that state.

My two cents.