What started as a washed out gravel road has become a naturally occurring sediment diversion that is helping to balance salinity levels and improve fish habitat south of New Orleans—to keep wetlands from disappearing, experts should keep Mardi Gras Pass and take control of its freshwater flows

The primary reason that nearly 2,000 square miles of prime fish and wildlife habitat have vanished along Louisiana’s coast is not erosion or development. It’s just that the land is constantly sinking, a phenomenon known as subsidence. While gradual, sea-level rise is already affecting coastal areas all over the world, and Louisiana is contending with rising water and sinking land.

Sediment delivered by annual flooding on the Mississippi River used to be the key to keeping coastal wetlands above the water line. But, when that sediment flow was cut off by flood-protection and navigation levees a century ago, wetlands started disappearing.

That’s why Louisiana’s coastal master plan calls for the construction of two major diversions, one east and one west of the river below New Orleans. Two control structures and canals will be built through the levees to deliver the sediment needed to help wetlands stay above the water line, serving as critical fish and wildlife habitat and better protecting coastal communities from storm surges.

Sediment delivery brings with it freshwater inundation, which will certainly change the makeup of the fisheries in the outfall areas. To minimize impacts to fisheries, the plan is to move water and sediment only when sediment loads are at their peak and cut back, or shut off, the diversions when river flows aren’t carrying as much sediment.

Extensive modeling has been conducted to try and predict the effects of the freshwater, but biologists have been careful to point out that there’s a degree of uncertainty considering river conditions, including sediment loads, water temperatures, and weather, in any given year.

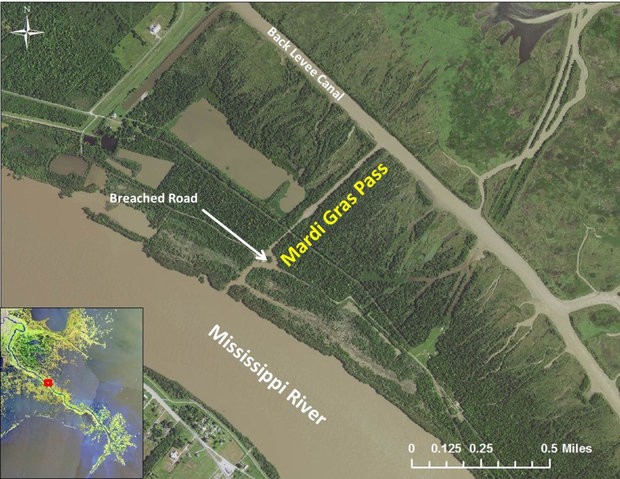

However, east of the river, near the small fishing community of Point a la Hache, hypotheticals can be replaced by a discussion of what is currently happening in the marshes, canals, bays, and lakes being inundated with freshwater and sediment from a break in the Mississippi River bank that has become known as Mardi Gras Pass.

Mardi Gras Pass earned its name because the first time it was observed flowing freely from the river and down an existing canal was on Mardi Gras in 2012, a year after record flooding reshaped many areas along the east side of the Mississippi below New Orleans. The force of the flood washed away a gravel road and cut the bank around an old control structure that once allowed a limited amount of river water to spill into the area, controlling salinity and improving oyster habitat. What started as a tree-snagged trickle of less than 5,000 cubic feet per second has turned into an uncontrolled diversion that is estimated to be moving about 35,000 cubic feet per second—coincidentally, the same rate of water flow is prescribed for the diversion Louisiana has planned.

John Lopez, director of the Coastal Sustainability Program at the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, is the one who gave the new cut its name and has been studying the impacts of the natural diversion very closely. Early on, he saw schools of shad bunched up in the flowing water and has since documented a drastic increase in sediment pouring into adjacent marshes and bays. Submerged vegetation aided by the fresh water now fills ponds and bays from near the mouth of the pass out to the edges of Black Bay.

Waterfowl habitat has also improved. Bass populations have exploded in the area, and it has also become popular among tournament anglers who are finding redfish feasting on bluegills, crabs, shrimp, mullet, and crawfish. White shrimp are also more plentiful. Speckled trout, Louisiana’s most popular saltwater sportfish, have reacted to the seasonal changes in salinity by moving away from Mardi Gras Pass when the Mississippi River is high, but returning to the area when the river drops.

As is the case with any discussion of diversions, either existing or planned, not everyone is happy with the changes in the area. Oyster harvests on public oyster beds near Mardi Gras pass are down about 85 percent over the last decade, though it has been noted by Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries biologists that this decline began before the cut opened. The state’s Oyster Task Force recently voted to commit $200,000 to examine closing Mardi Gras Pass.

While the indication of negative impacts to oysters in public harvest areas and shifts in fisheries to more freshwater and freshwater-tolerant species is undeniable, closing Mardi Gras Pass would be a mistake. Controlling it with gates to maximize sediment delivery and force freshwater into adjacent marshes would be an optimal solution, especially since that’s what is recommended by those examining diversions in the Master Plan.

Simply plugging the hole and not allowing the river to flow at all is short-sighted. The Mississippi River is supposed to be connected to its adjacent wetlands. Any connection provides benefits to a sediment-starved system.

Coastal estuaries should be managed for a diverse array of fish and wildlife, not just oysters and popular sportfish species like speckled trout. If one of the primary solutions for trying to fix Louisiana’s ailing coastal wetlands is to reconnect them to the river that once built them it sure doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to completely sever one of the few existing connections between river and marsh.

First image courtesy of LPBF.