Explore some of the West’s most cherished backcountry landscapes through the lens of outdoor photographer Tony Bynum, and learn how you can take an active role in conserving these areas for future generations of hunters and anglers

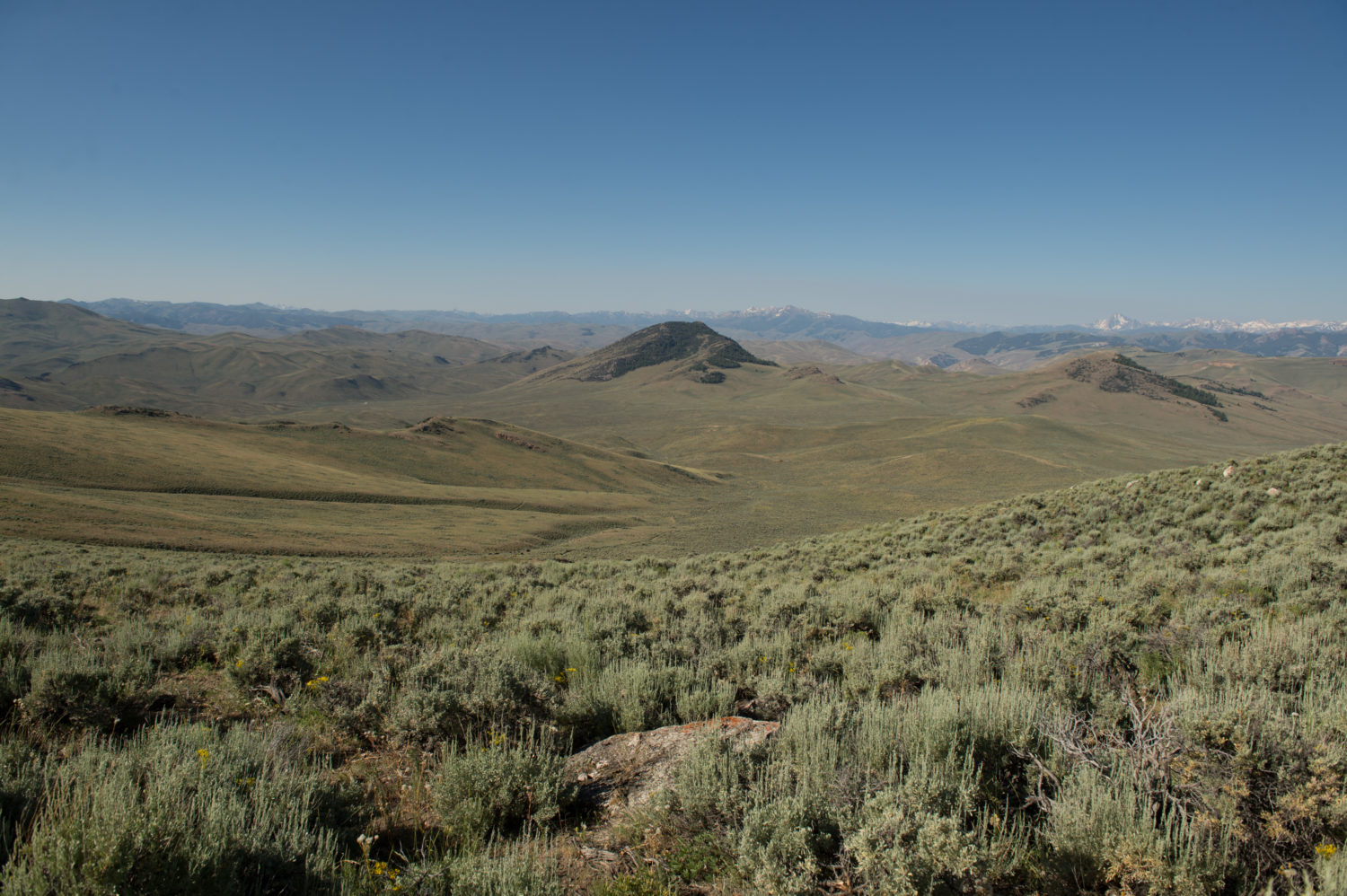

In Idaho’s High Divide, there exists 7.4 million acres of wildlife habitat and largely untamed public land. Three times the size of nearby Yellowstone National Park, the High Divide sees just a fraction of the use that the famed park does. Beginning this year, the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service are undertaking expansive planning efforts to guide the future of these lands, which represent 20 percent of the public ground in Idaho. I recently explored the area with photographer Tony Bynum to document some of the stunning and valuable landscapes at stake in this process. Here’s what we saw.

The High Divide planning area—comprised of both BLM and Forest Service land—is home to mule deer, whitetail deer, elk, pronghorn antelope, moose, mountain goats, and bighorn sheep. It is where half of Idaho’s mountain goat hunters and 73 percent of the state’s Rocky Mountain bighorn hunters draw tags. In 2016, more than 18,500 hunters spent 88,842 days within the Salmon-Challis National Forest and public lands overseen by the BLM’s Salmon and Challis field offices.

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game has recently discovered that the High Divide is also home to vast amounts of pronghorn antelope winter range and migration routes that stretch up to 80 miles. It also features the Sand Creek Desert, which is the wintertime home of more than 10,000 big game animals—elk, deer, moose, and pronghorns.

The BLM is in the first stage of rewriting its Resource Management Plans for 3.14 million acres of this area. The plans will set the direction for ranching, mining, and recreation for decades to come, so this is a critical opportunity for sportsmen and women to rally around the need for these lands to be managed for the benefit of hunting and fishing and the $887-billion outdoor economy we support.

The Salmon-Challis National Forest is also planning for the future of 4.3 million acres of public forest. Over the past nine months, the agency has assessed the health of the forest and explored its issues and future challenges. Forest officials will present alternatives for management over the next 12 months.

This is an important public process, and as citizens of Sportsmen’s Country—the public lands where the majority of hunters and anglers have the unique privilege of pursuing our outdoor traditions—it is critical that we all speak up.

Here’s what you can do.

In addition to commenting on the individual plans (when available), there are a number of ways you can act now to influence the management of our national public lands:

- Sign our new Sportsmen’s Country petition. Let decision makers know that it isn’t enough to simply pledge to keep public land public. We need responsible management of our public lands to ensure a positive future for hunting, fishing, and our way of life.

- Contact the TRCP’s Idaho Field Representative Rob Thornberry directly at rthornberry@trcp.org. He is tracking the plans closely and will make sure you have the opportunity to engage in the process when the time is right.

- Or, simply join the TRCP—it’s free! We’ll keep you posted on this and any other conservation issues affecting your ability to access quality places to hunt and fish.

Need some more public lands to daydream about? Check out other BLM landscapes worthy of conservation here and here.