Planning For Habitat

The Lolo and Bitterroot National Forests stretch across approximately 3.5 million acres in western Montana and provide important wildlife habitat, coldwater fisheries, and recreational opportunities that support thousands of jobs in the region. But the land-use plans that guide the U.S. Forest Service’s management of these vast public lands were written 35 years ago and need updating to address modern challenges.

In recent years, a seemingly limitless demand for outdoor recreation opportunities, the presence of noxious weeds, and the impacts of decades of fire suppression combined with warming conditions are putting greater pressures on wildlife and habitat in western Montana. Simultaneously, incessant exurban development continues to fragment winter and transitional ranges for elk and deer on neighboring private lands. The Lolo and Bitterroot National Forests’ land-use plans must be updated to conserve the wildlife values of these public lands.

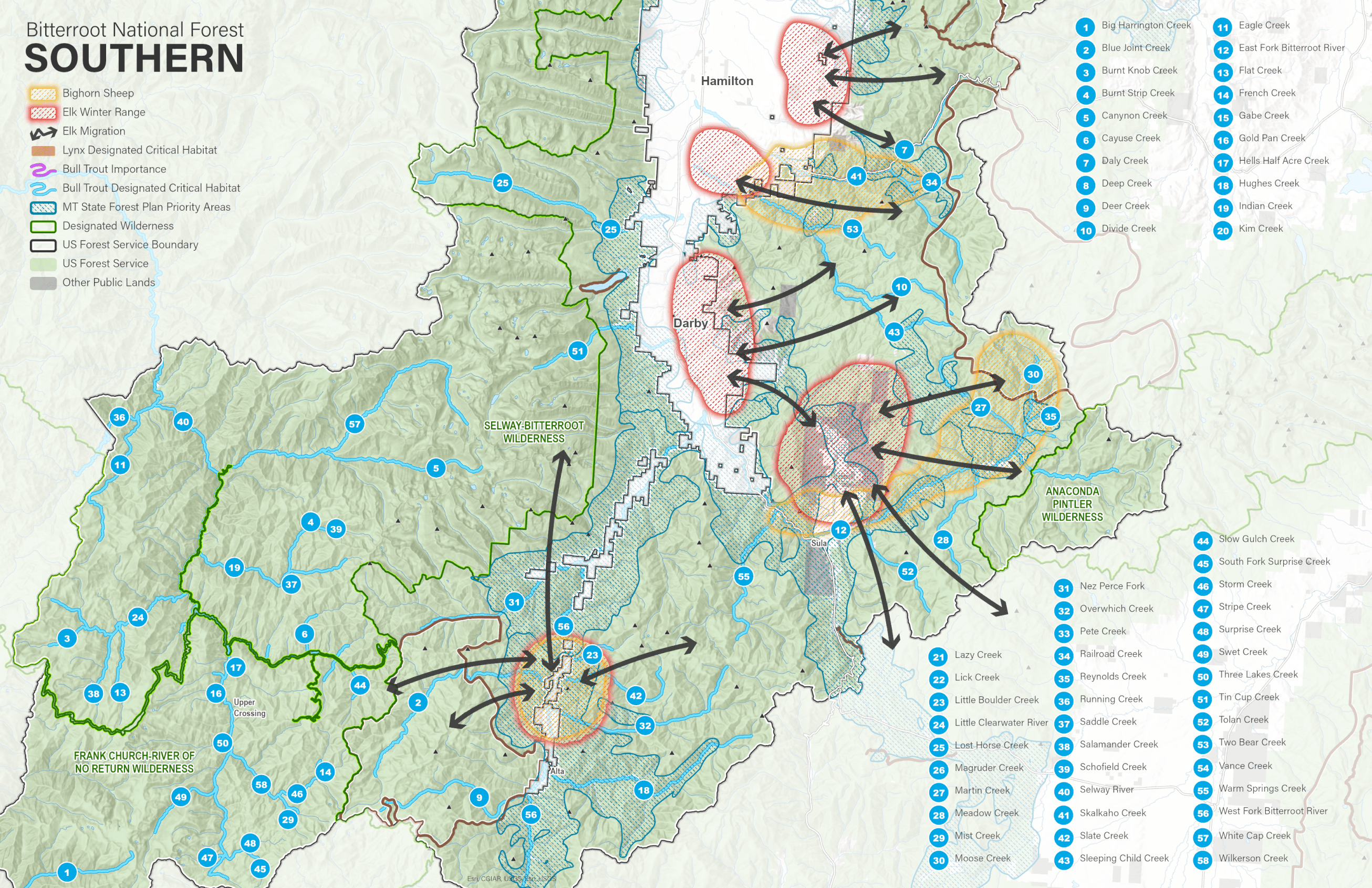

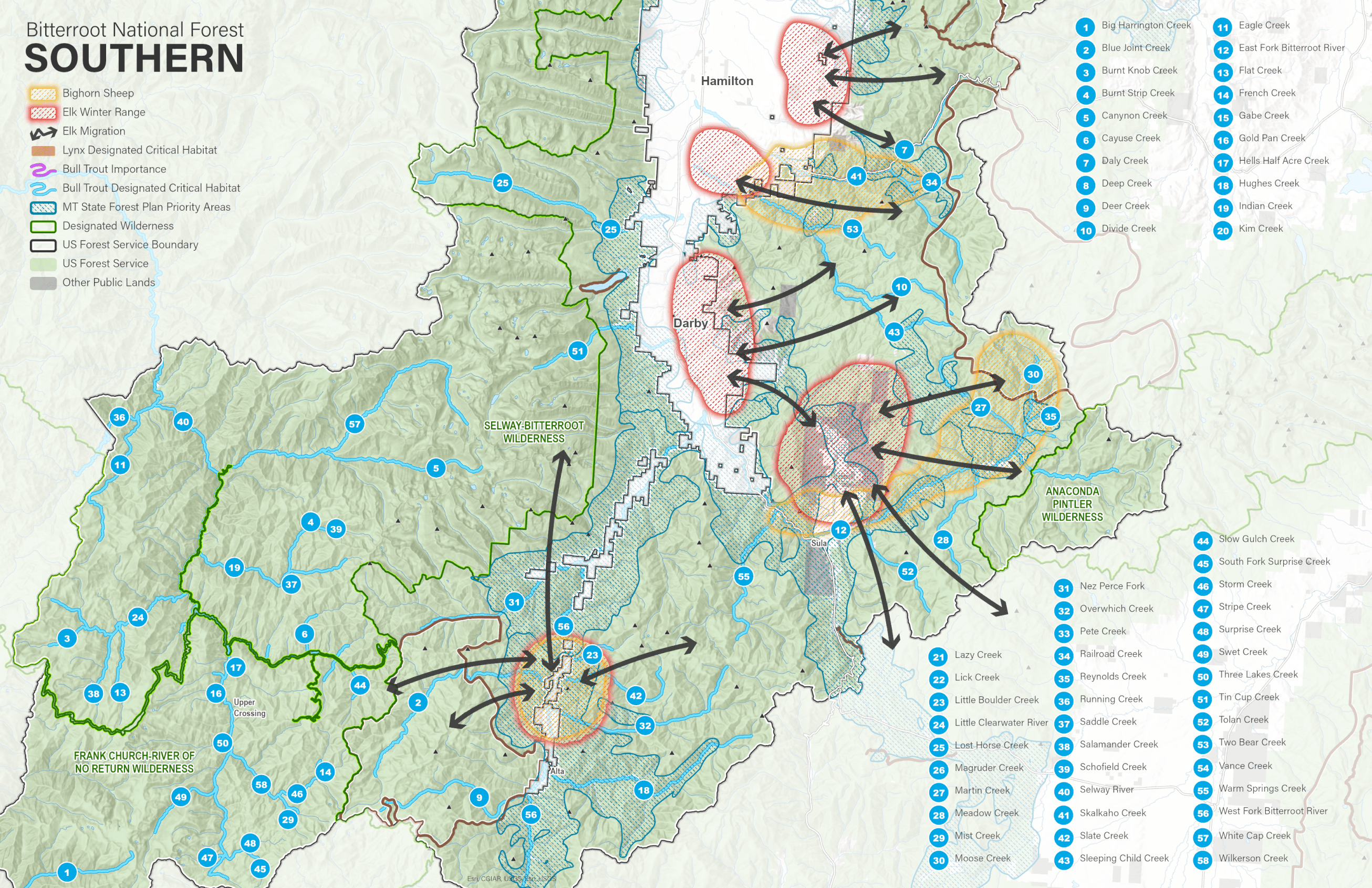

The Bitterroot and Lolo National Forests are home to several important big game migrations and winter ranges for elk, mule deer, and bighorn sheep in western Montana. In the decades since the existing forest plans were finalized, new information about wildlife migrations has been collected in a vast research effort. The Forest Service must incorporate the latest science, utilize the best-available conservation tools, and prioritize coordination with other stakeholders to safeguard big game as the agency initiates the forest plan revision process for these public lands.

Below are six key policy recommendations to ensure that the revised forest plans for the Bitterroot and Lolo National Forests conserve these migration routes, winter ranges, and Montana’s renowned big game populations.

Utilize GPS collar data and credible anecdotal information about big game movement across the forests—including high-priority migration routes and winter range—and establish management areas to provide consistent management direction and conservation for these habitats across the planning area.

Develop standards and guidelines to manage open road and trail densities at or below determined levels to maintain habitat function, manage for invasive species, and require the addition of wildlife passages or wildlife-friendly design components for existing and new infrastructure. This includes establishing seasonal restrictions on certain uses of the land to avoid impacts on big game at key stages in their lifecycles, as well as actively managing both motorized and non-motorized recreation.

Collaborate with other federal and state agencies, tribes, and local governments when developing plan components for habitat used by big game species. Specifically, the USFS should work with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks and reference the agency’s mule deer and sheep management plans, as well as its elk management plan currently under revision.

Prioritize strategic land acquisitions that connect and conserve seasonal habitats, reduce habitat fragmentation, and consolidate management—in conjunction with private, county, state, and tribal land conservation efforts—to protect important winter ranges that are threatened by development.

Prioritize vegetation treatments to improve forage quality and reduce conifer encroachment on open grassland meadows, brush fields, and winter ranges. In addition, the plan should specify that livestock grazing in known bighorn sheep ranges should be managed to prioritize maintenance of overwinter forage for bighorn sheep.

Establish management areas for backcountry conservation to protect habitat security for big game in large blocks of summer range and transitional ranges and to provide for semi-primitive non-motorized recreation—including hunting and fishing. Incompatible development activities should be restricted, and active habitat restoration should be directed to restore wildlife habitat and ecosystem function and processes, while facilitating climate resilience and adaptation.

Theodore Roosevelt’s experiences hunting and fishing certainly fueled his passion for conservation, but it seems that a passion for coffee may have powered his mornings. In fact, Roosevelt’s son once said that his father’s coffee cup was “more in the nature of a bathtub.” TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to bring together his two loves: a strong morning brew and a dedication to conservation. With your purchase, you’ll not only enjoy waking up to the rich aroma of this bolder roast—you’ll be supporting the important work of preserving hunting and fishing opportunities for all.

Learn More