Hunting & Fishing Access

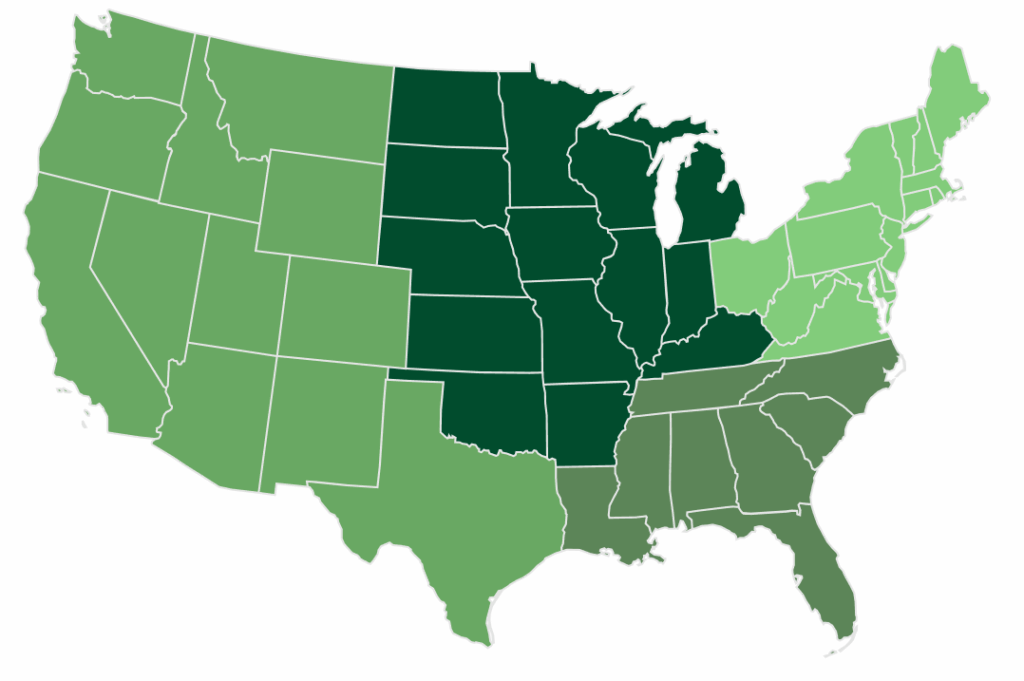

America’s 640 million acres of national public lands provide irreplaceable hunting and fishing opportunities to millions of Americans.

Learn More About AccessWe’re working to safeguard America’s public lands so hunters and anglers always have quality places to pursue their passions.

Brian Flynn, Two Wolf Foundation's Story

Following a distinguished career in the U.S. Army, lifelong outdoorsman Brian Flynn returned home from a deployment in Afghanistan and…