Whether you’re headed out on the road or straight for your couch, pass the time by getting informed on some of the most pressing conservation issues affecting hunters and anglers

Top photo by Larry George II on Unsplash

Top photo by Larry George II on Unsplash

Highlights success stories in four Western states and offers guidance to NGOs looking to adopt a new approach to community engagement

The Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and Heart of the Rockies Initiative today released a report on how conservation and outdoor recreation missions align with supporting the well-being of rural communities across the United States.

The report features projects in four Western states where conservation organizations and outdoor recreation groups engaged with rural communities in ways that recognize mutual values and benefits, as well as the intersection of conservation, recreational opportunities, and community economic development. The case studies featured in the report include Aberdeen, South Dakota; Lincoln, Montana; Montrose, Colorado; and Southeast Alaska.

“Quite simply, rural communities with strong economies are more likely to be in a position to support conservation and recreation, including policies that benefit fish and wildlife habitat,” said Joel Webster, Vice President of Western Conservation with the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “This report showcases what can be accomplished when conservation organizations and outdoor recreation groups adopt the belief that community well-being is critical to the success of their work.”

The report points out that in recent years, a number of conservation organizations have recognized that “rural community revitalization and economic opportunities are important values; that resource conservation and outdoor access can be aligned with those values; and that hunting and fishing organizations, land trusts, and other recreation and conservation groups can provide meaningful support for community-led development priorities in ways that are consistent with a conservation organization’s core mission.”

In the community of Lincoln, Montana, conservation organizations have worked to augment community capacity and to implement the community’s Envision Lincoln plan, including applying for federal and state grants and bringing together people and resources to support community goals.

“After losing our primary industries–logging and mining–we had to reinvent ourselves. Outdoor recreation offers the opportunity for our businesses to keep their doors open and thrive in an every changing economy,” said Laurie Richards, former President of the Lincoln Chamber of Commerce and owner of the Wheel Inn restaurant.

In Southeast Alaska, where local communities were hit hard by the Covid pandemic, the Sitka Conservation Society pivoted capacity and programs to support urgent community needs in ways that helped create genuine and long-term trust-based relationships.

“Sitka Conservation Society’s Community Conservation Corps program gave us experience with how nonprofits can leverage coronavirus relief funding to employ local residents and subcontractors and spread these funds to local businesses, while investing in projects that have benefits for locals as well as our recreation and visitor industry,” said Katie Riley, Policy Director for the Sitka Conservation Society.

“The Heart of the Rockies Rural Development Program was developed on the premise that the success and sustainability of conservation in the Rocky Mountain West is inextricably linked to rural community vitality and economic well-being,” said Gary Burnett, Executive Director of the Heart of the Rockies Initiative. “In highlighting these four case studies, this report illustrates what can be accomplished when stakeholders recognize the alignment between these interconnected priorities.”

Click here to download a copy of the report.

Photo: @NickMKE via Flickr

The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee has unanimously passed a historic compromise to invest in wildlife crossings, disaster prevention, climate resilience, and public access as part of a major infrastructure package, sending the bill to the full Senate for a vote.

The Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act, commonly called the Highway Bill, invests $350 million over five years in a competitive grant program dedicated to the construction of wildlife crossing structures, including over and under passes. These crossing structures help connect otherwise unavailable habitats that benefit pronghorn antelope, mule deer, and black bears.

“This remarkable agreement will preserve wildlife and human life by reducing vehicle-wildlife collisions,” said Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “Our highway system has historically fragmented big game habitat and migration corridors, but this bill recognizes that we can create jobs, maintain modern infrastructure, and improve our natural systems. The bill also builds climate resilience as we grapple with the impacts of weather events and improves public access to hunting, fishing, and other recreational opportunities. We want to thank Chairman Carper and Ranking Member Capito for leading the effort to ensure this transportation bill keeps wildlife habitat connected.”

This investment is the first of its kind in a national wildlife crossings initiative. The TRCP began working on this issue back in February 2019 by hosting a workshop with biologists, planners, and engineers from multiple state and federal agencies to discuss the issue of wildlife-vehicle collisions and how to safeguard migrating wildlife. Since that time, the TRCP has spearheaded the legislative and grassroots effort with many partner organizations and more than 12,000 hunters and anglers who have asked lawmakers to invest in wildlife crossings.

Other important provisions in the Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act include:

Hunters, ranchers, and land managers partner for the benefit of wildlife and working lands

As snow recedes in the Centennial Mountains along the Idaho-Mountain border and in the high country of Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, big game animals are on the move.

Following the spring green-up that comes with snow’s retreat, roughly 10,000 deer, elk, moose, and pronghorn are leaving the Sand Creek winter range—located roughly 50 miles northeast of my home in Idaho Falls— and heading primarily north and east to the high-country headwaters from Camas Creek east toward Yellowstone’s Boundary Creek and Falls River.

The seasonal movements of these animals are one of the wonders of the West, especially considering the challenges presented by habitat lost to severe wildfire, the proliferation of fences and other barriers, and the near-constant encroachment of more second homes, roads, and major highways. With Idaho’s rapid growth in recent years, keeping this migration route intact will be a major challenge.

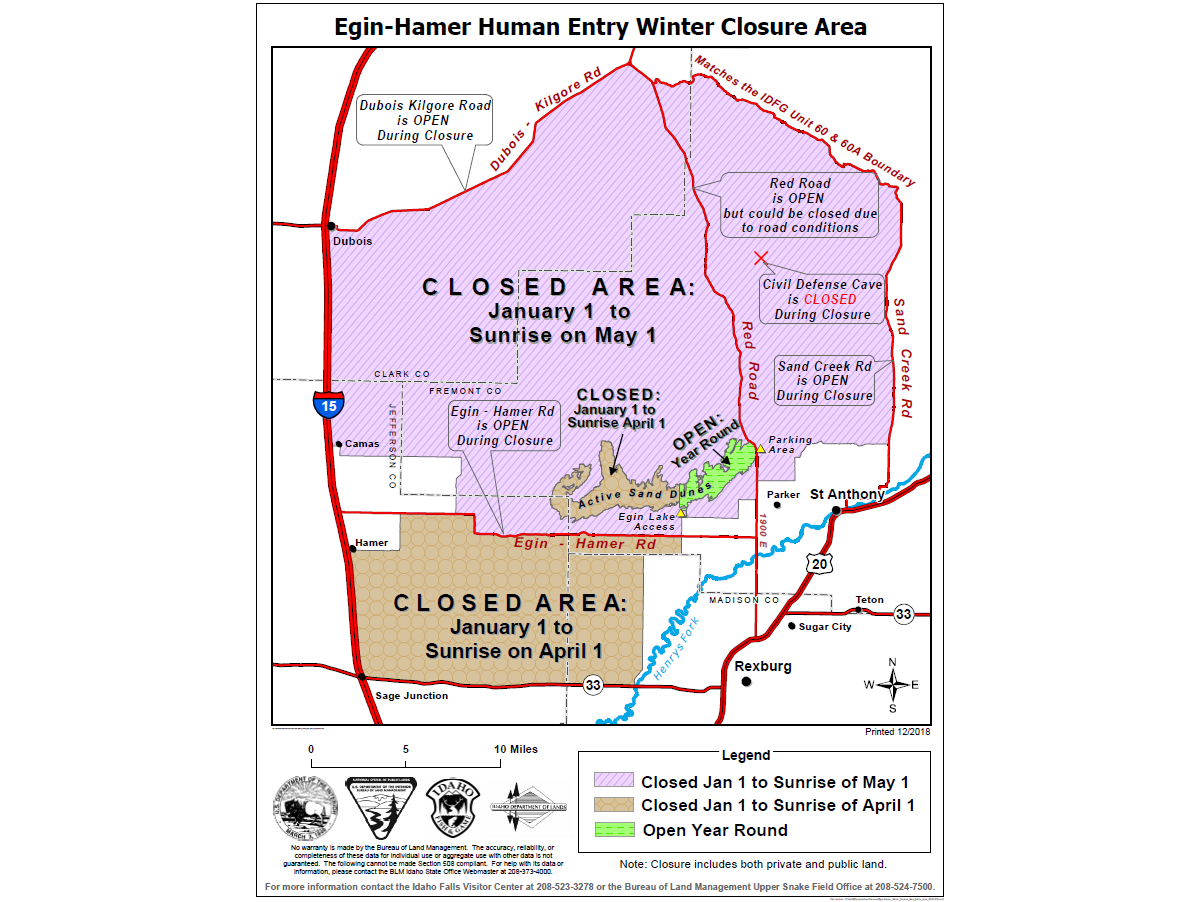

Fortunately, a blueprint for success has been developed at the wintertime terminus of this major migration, the Sand Creek desert, which sits between the towns of St. Anthony and Dubois in eastern Idaho’s Fremont and Clark counties. The winter range is a 500,000-acre patchwork of Bureau of Land Management public lands, endowment lands managed by the Idaho Department of Lands, and private property.

Despite the differences in priorities of the various stakeholders, these agencies and landowners have teamed together to conserve the winter range while also allowing the local ranching industry to thrive.

The partnership began in the 1970s when local ranchers applied to have 4,000 acres of big game winter range converted to cultivation for potato farming. The BLM rejected the proposal, but the ensuing dialogue resulted in the Sand Creek Habitat Management Plan, adopted by the BLM, Idaho Department of Lands, and Idaho Department of Fish and Game, which outlined a cooperative management approach to enhance the elk winter habitat in the BLM’s Sands Habitat Management Plan. One of the plan’s main goals was to help a fledgling herd of elk that was first identified in the area in 1947, and, in the late 40s or early 1950, the Fremont County Sportsmen Association also transplanted 12 elk to the area from Yellowstone National Park.

The partnership was tested in the 1980s when local ranchers and the counties asked the BLM to turn the Egin-Hamer Road into a year-round, farm-to-market road. Again, the local landowners lost their request at first, but cooperation won out in the end. In exchange for converting the road into a year-round thoroughfare, all of the interested parties agreed in 1987 to an annual closure for the winter range that limited all human entry from Jan. 1 to May 1, preventing human disturbances to big game animals already stressed by harsh seasonal conditions. It is a model of conservation that came to pass because of cooperation and negotiation.

More than 30 years later, the group of agencies, landowners, and sportsmen that created the wintertime closure are back at the table, working for the best interests of wildlife and the local ranching community. Mobilized by a 2019 wildfire that burned roughly 20 percent of the winter range, conservationists, sportsmen, landowners, state biologists, and federal land managers have joined forces yet again. This time, the priority is to build firebreaks to protect the remaining healthy winter range and design vegetation treatments to restore the overgrown stands of aging sagebrush. The goals of their collaboration are preventing large wildfires, improving wildlife habitat, and providing for a working landscape.

Already this spring, deer, elk, moose, and pronghorn have largely left the Sand Creek Desert, riding the green wave of new forage to the high country of the Centennials and Yellowstone. There they will calve and fawn. They will fatten over the summer and fall until deep snow pushes them back down from the mountains. The winter range will be waiting, protected by meaningful conservation safeguards, and in the good hands of Idahoans who are working together.

Sand Creek is a template for how to manage challenges facing winter ranges and other valuable wildlife habitats. More importantly, it is a model of the type of cooperation that has been at the heart of our country’s greatest conservation successes. That same collaborative spirit will be needed on future BLM and Forest Service planning efforts as we continue our work to ensure the West’s big game herds can move between the seasonal habitats they need to thrive.

This video is the last in a five-part series detailing conservation projects powered by Pennsylvania’s Keystone Recreation, Park & Conservation Fund, which has provided state-level matching dollars for land acquisition, river conservation, and trail work since 1993. This series is the result of a collaboration between the TRCP and Trout Unlimited where the goal is simply to celebrate conservation success stories that make us all proud to be able to hunt and fish in Pennsylvania. To view other videos in the series, visit our YouTube playlist. For more information on the Keystone Fund, you can visit: https://keystonefund.org

It is no secret that the pandemic has generated a renaissance in outdoor recreation. Hunting, fishing, and boating were all important parts of this growth here in Pennsylvania. In 2020, hunting license sales increased by 5 percent, fishing licenses were up 20 percent, and boat registrations climbed an impressive 40 percent. The growing number of hunters, anglers, and boaters in 2020 and 2021 will only help to boost a robust $26.9-billion outdoor recreation economy in Pennsylvania.

Increased interest in the outdoors shines a spotlight on the conservation challenges we face, but it also creates an opportunity to showcase what Pennsylvania has already done right by funding habitat and public land improvements and protecting water quality.

It is easy to see why water-centric activities grew intensely across the commonwealth in 2020—with 86,000+ miles of rivers and streams, Pennsylvania is a water-rich state. Many state parks and forests saw 100- to 200-percent increases in visitation, but parks with large water features, like the reservoir in Beltzville State Park outside of Jim Thorpe, saw as much as a 400-percent increase in foot traffic.

The revenue generated from water-based recreation recognizes just a portion of the return on our investments into these resources. As many sportsmen and sportswomen mention in our videos, these rivers and streams facilitate connection—with nature and with each other—and represent our ability to sustain uniquely American outdoor traditions for generations to come. With about 30 percent, or at least 25,000 miles, of streams in Pennsylvania impaired for one or more uses, plenty more investment is needed to realize the full potential of our waters.

This is why dedicated conservation funding matters to hunters and anglers in Pennsylvania. For the last video in our series on conservation successes, we look back at the individual projects featured on Valley Creek, Monocacy Creek, Brodhead Creek, and the Lehigh River to drive home what’s at stake if we lose conservation funding sources like the Keystone Recreation, Park & Conservation Fund and Environmental Stewardship Fund.

It’s clear that whether flyfishing fabled waters steeped in the roots of American history, hunting waterfowl on newly minted public game land, or chasing wild trout through some of the most densely populated regions on the east coast, one thing is true: Water connects us all.

Theodore Roosevelt’s experiences hunting and fishing certainly fueled his passion for conservation, but it seems that a passion for coffee may have powered his mornings. In fact, Roosevelt’s son once said that his father’s coffee cup was “more in the nature of a bathtub.” TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to bring together his two loves: a strong morning brew and a dedication to conservation. With your purchase, you’ll not only enjoy waking up to the rich aroma of this bolder roast—you’ll be supporting the important work of preserving hunting and fishing opportunities for all.

Learn More