Some states say sage grouse numbers are up, while others have been forced to close popular hunting units—so is it good news or bad news for this iconic gamebird?

As the leaves begin to change, some hunters will experience changes to their opportunities for pursuing sage grouse in parts of the West. Because of lost habitat and fewer birds on the landscape, several states have yet again adjusted their hunting seasons or closed some popular hunting units altogether.

In Colorado, hunters will not be pursuing sage grouse in two of the best units in the state because of lost habitat and fewer birds counted for three consecutive years. Nevada has reduced season lengths considerably across several of its hunt units, closed some due to fire, and offered 40 percent fewer special permits to hunt grouse on the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge.

Idaho, once a major stronghold for sage grouse offering liberal seasons and bag limits, now allows just one bird per day for either a 2- or 7-day season, depending on the unit. Some units have been closed completely. And the Gem State is contemplating moving to a draw system for limited sage grouse licenses, as Oregon and Utah already have.

Oregon recently reduced the number of limited permits available to hunters for the 2020 season. And sage grouse hunting remains closed in parts of Wyoming, the Dakotas, California, and Washington.

At the same time, if you follow such things closely, you would have seen news stories reporting that lek counts—or the number of males seen at breeding grounds that serves as an indication of the overall health of the population—of certain sage grouse populations are up in some places. So, how is a hunter to interpret these reports when facing season closures or changes? Is it good news or bad news for the birds?

Looking at the Long-Term Trend

It’s the difference between looking at a single moment in time, outside the context of weather and habitat conditions, and considering these numbers within the bigger picture.

In fact, 2020 sage grouse lek counts were mostly similar to 2019, with slight decreases and, yes, some gains across the region. Wyoming, which is home to the largest number of sage grouse, reported a 1.5-percent dip in males attending their leks, while Idaho saw their statewide counts increase by 2.5 percent compared to 2019. Montana was a bright spot in the West, having experienced mostly good habitat conditions, and it showed—more males showed up to the leks.

But most sage grouse totals remain well below 2016 levels. In fact, the long-term trend remains negative, indicating that sage grouse have not yet turned the corner and stabilized or started an increase. Since 1965, counts of males at leks continues to show an average 2-percent range-wide decline each year.

Keep in mind that the 2016 lek counts, which we’re using as the high bar here, would mark the lowest high-point of any on record—so, a spike on the chart, but at the bottom of a steep decline. The 63-percent increase recorded that year, the result of timely precipitation levels and good habitat conditions, was compared to the second-lowest count of lekking males EVER from 2013, when habitat was deep in a multiple-year drought.

The increase was great news at the time, and the 2015 and 2016 hunting seasons were rather spectacular. Personally, I was able to finish off my Wyoming 2-day possession limit of four sage grouse in very short order, give my oldest dog his last grouse retrieve, and do it all in habitat the likes of which I hadn’t seen in some time.

Changes to seasons and bag limits are necessary as a response to the habitat conditions and status of the birds this season, but it’s a letdown for many hunters who have memories, like this, of fantastic sage grouse hunting from their past and as recently as five years ago.

But dry conditions have returned once again to much of the West, and all Western states have recorded steep declines in sage grouse numbers, even if they are seeing a small rebound this year. From 2016 to 2019, there were 30 to 60 percent fewer male sage grouse dancing on their breeding grounds across the eleven states.

Managing the Harvest

We should talk a little about how wildlife managers make the call to cut bag limits or alter seasons. It has been many years since hunting was a primary threat to sage grouse populations at the beginning of the 20th century, but state wildlife agencies generally manage these birds cautiously. Here’s why.

A foundational principle of game bird management is that there are usually similar death rates whether they are hunted or not. The technical term used for this scenario is compensatory mortality, which means that regulated harvest of most game birds compensates for otherwise inevitable mortality from other sources.

Sage grouse are a little different though. They live longer, have much higher over-winter survival than most game birds, and can fly long distances to seek better habitat conditions, if necessary. But they also have a relatively low reproductive output compared to other game birds—most will readily re-nest after losing their first clutch of eggs, while sage grouse often do not. As such, harvest is not always compensatory and may add to other sources of mortality.

State wildlife agencies therefore continually adjust season lengths and bag limits to ensure that less than 10 percent of the estimated total population of sage grouse are harvested each fall.

This is a short-term consequence for hunters, but there are long-term challenges to consider.

Habitat Is the Cornerstone

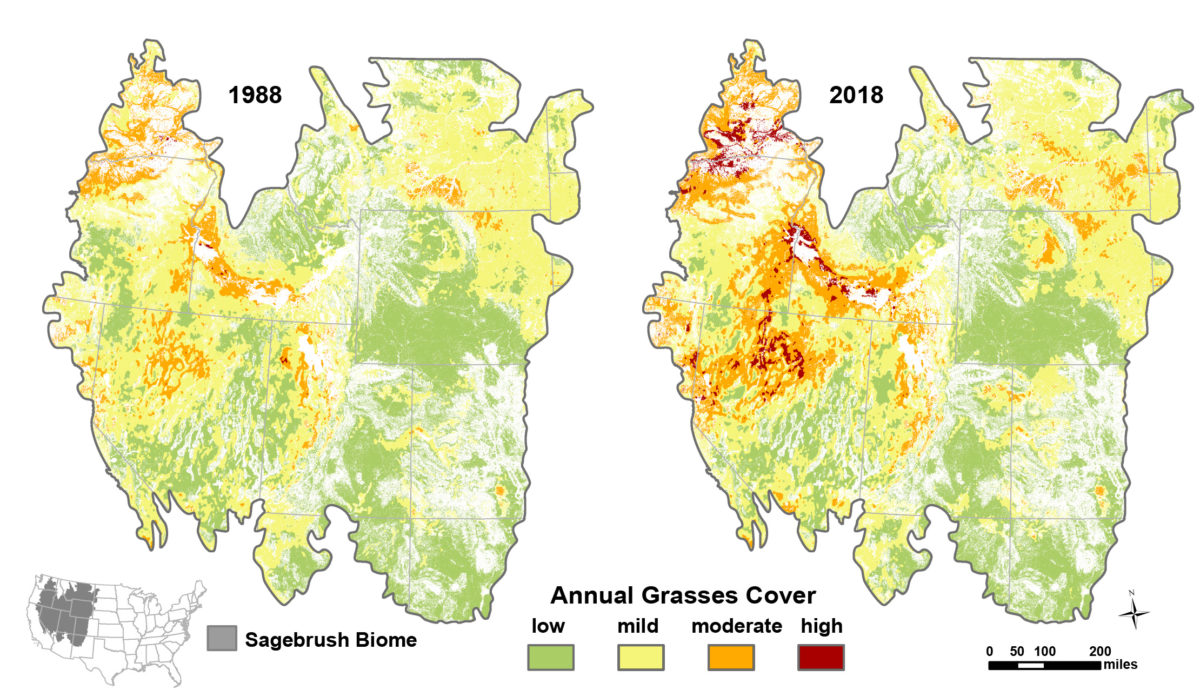

While weather conditions are the usual culprit of dramatic short-term fluctuations affecting sage grouse, long-term increases or declines are driven by changes in the amount and quality of habitat. Unfortunately for grouse—and hunters—prime sagebrush habitat continues to be lost at an alarming rate.

Wildfires, often fueled by invasive annual grasses, have consumed millions of acres of sage grouse habitat in recent years. Nevada, for example, has lost nearly 30 percent of its sage grouse habitat to fire over the past 20 years.

Worse yet, researchers estimate that if the current wildfire cycle continues, sage grouse populations could be cut nearly in half over the next 30 years.

According to recent information compiled by the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, wildfire is responsible for the loss of about 1 percent of sage grouse core habitat—the best of the best forage, cover, and nesting areas—each year from 2012 to 2019. This doesn’t even account for habitat lost due to energy development, urbanization, or other factors.

In addition to outright loss, some existing habitat is so degraded that it is no longer suitable for sage grouse, and habitat improvement is underfunded. And there remains a huge backlog of restoration needs across the West.

That lost habitat equals fewer birds, and fewer birds ultimately will mean hunters’ seasons may be cut short or perhaps eliminated—at least temporarily.

The Seasons Ahead

The crystal ball for sage grouse is somewhat murky, but the future is largely in our control. The question is do we want large expanses of healthy sagebrush habitat across the American West? Do we want to see a thriving sagebrush ecosystem that provides benefits to all – hunters, ranchers, hikers, and, yes, even developers?

Will all Western states ultimately be forced to employ a lottery draw system for sage grouse hunting or continue to close certain areas?

The answer will depend on how we choose the conserve the sagebrush ecosystem. We cannot control drought or harsh winters, but we can do something about improving habitat and ecosystem health.

Conservation is a long-term endeavor that requires commitment and funding to ensure problems are resolved, habitat restored, and populations recover to sustainable levels. For sage grouse, this means full implementation of all state and federal plans conservation strategies and continued incentive programs for private landowners. It means coordinated efforts to combat fire and invasive plants. And it means achieving balance with other uses of the land.

The long-term future of sage grouse and our opportunity to continue hunting them rests on habitat. If we can stop the continual loss of habitat and restore healthy conditions in the sagebrush ecosystem, sage grouse and hunters could see a brighter and more sustainable future.

I think that there needs to be some real communication with people that own land where sage grouse thrive. I own such land and would be willing to make a conservationist dream come true. I have tried to get interaction from other conservationist groups but the real story is that conservation groups want to make noise without real solutions. The real solutions are easy in principle but hard on the faint of heart.

Years ago an old friend told me about the WPA days and one of the things they did was to poison the Richardson’s ground squirrels in Colorado up in the Walden area. After that he said the flocks of sage grouse flying from the roosting areas would block out the sun twice a day. Those ground squirrels are notorious nest robbers. Something the scientists probably have not thought of. The other thing I can’t figure out is why anyone would want to eat a sage grouse. I have but don’t care for sage flavored liver and that is the best I could get out of them.

Scientists have “thought of it”. Video cameras on nests have demonstrated that while ground squirrels may try, their mouth gap is not large enough to break an egg. They will chew on hatched eggs leaving the impression (tooth marks) that they broke and consumed them. Relative to taste/texture, if a sage-grouse tastes or feels like liver, the hunter and cook mishandled it.

Dump Trump to save the habitat – we need leaders that care about hunters, not one that cares about gun sales & political donations

Didn’t Trump sign the Great Out Doors Act? Didn’t he stop the Pebble Mine and isn’t his son and adviser an avid Hunter? He has been listening to Conservation needs. Let’s not put all our problems on him.

Thanks for this articulate piece on what we need to support now and forever: habitat, habitat, habitat. Our legislators at state and federal levels need to be as articulate and supportive as we are.

Thanks for this analysis of sage-grouse consevation challenges. And thanks to TRCP for your advocacy for the scientific management of the sagebrush ecosystem.

I’ve hunted Sage Grouse in California [2 day season, 1 bird limit] and Oregon [lottery permit, 9 day season, 2 bird limit]. In the past I’ve seen many birds in the North Mono [CA] hunting zone. In Oregon I’ve hunted in 3 zones [1 of them 2 times]. In 2 of those 3 zones I did not see a feather, a dropping, or a track, nor a sighting of a bird at a distance. In the other I’ve encountered birds both times. It appears that vast seas of sage habitat are required w/ little fragmentation. In both states I’ve seen only very limited effort at habitat improvement. I’ve also seen widespread cattle grazing on the public lands. Thankfully, little mining, energy or other impactful activities. We can expect either further restriction or an end of hunting for the great bird.

Trumps illegal appointment of BLM William Pendlay has been a boon for get rich energy companies at the expense of our public lands and sage grouse. His denial of global warming is especially apparent in the West with drought and fires ravaging the landscape. 98% of the grouse are now gone because of politics and poor land management.

West.

Pendley was legally appointed as interim head of BLM. You may not like his policies but there is no need to lie about his appointment or Trump.

Hi Ed. Good article and good to see you are still out doing biology.