An in-depth look at four major restoration projects that have directly benefited anglers and hunters by improving coastal habitats using Deepwater Horizon penalties

INTRODUCTION

The explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig and the subsequent oil spill in the spring and summer of 2010 was the worst environmental disaster in American history.

In the decade since this tragedy, oil spill penalties have been invested in projects that directly address the damage, improving the outlook for the Gulf of Mexico’s coastal communities and fish and wildlife habitat. There is optimism that the Gulf can recover from the unprecedented ecological threats, but reversing the long-term decline of the region’s coastal ecosystems and water quality will continue for decades to come.

Oil Spill Hits Habitat Already in Crisis

From April 20, 2010 until nearly five months after, oil gushed from the Macondo Well, located a mile below the Gulf of Mexico’s surface and 50 miles from Louisiana’s coast. An estimated 210 million gallons of crude flowed into the Gulf, casting a long shadow of uncertainty on the future of some of the world’s most fertile fishing grounds.

In Louisiana, coastal communities were still struggling to recover from the devastation that Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Gustav, and Ike had wrought over the previous five years. Then, the Deepwater Horizon exploded, killing 11 men.

The state’s coastal habitats had been losing wetlands at a rate unmatched elsewhere in the nation, due to a combination of dams and levees cutting off sediment from the Mississippi River and the construction of thousands of miles of oil and gas canals and deep navigation channels. Suddenly, its coast faced a new threat that would certainly precipitate further habitat destruction.

Barrier islands, usually teeming with bird life and recreational fishermen in the spring and summer months, were among the areas hardest hit by the spill. Thick mats of weathered oil coated surf zones and cleanup crews scrambled to remove the tarred sands.

Bait and tackle shops and charter boat operations had done all they could to keep business going after the hurricanes, but they were shuttered once again. Anglers across the Gulf were anxious to hook up their boats and head to the coast, but oil coated their favorite shorelines and boat launches were crowded with cleanup crews.

There was no way to undo the damage caused by the negligence of those responsible for the disaster. Instead, the challenge for state, federal, and local leaders was to use the enormous penalties paid by BP, Transocean, Haliburton, and others to help fish, wildlife, and people recover from this unprecedented ecological and economic catastrophe and address the long-term ecological challenges that had been worsened by the spill.

The Numbers: From Fines to Fish Habitat

In 2015, BP—as the primary responsible party—agreed to pay $18.7 billion to the five Gulf of Mexico states for the ongoing environmental restoration efforts after the spill. Even earlier, BP had agreed to provide $1 billion in what was called “early restoration” funds to help the Gulf States begin addressing the damage to beaches, barrier islands, wetlands, and other habitats, while repairing lost access for recreational and commercial fishing. In all, BP has paid $54 billion for its part in causing the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Other settlements provided $2.4 billion to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund to help states restore and protect vital fish and wildlife habitat. In Louisiana, the GEBF is providing $1.2 billion for beach and barrier island restoration and the construction of sediment diversions along the Mississippi River.

In all, Louisiana alone is set to receive nearly $9 billion in fines and penalties over the next two decades—all of it committed to building reefs, enhancing coastal fisheries, and restoring vital wetland, beach, barrier island, and ridge habitats. To date, approximately $900 million has been spent on a variety of projects in the state, including the restoration of the state’s largest pelican rookery, extensive shoreline protection projects, and the largest beach and barrier island revival in state history.

The infusion of oil spill fines and penalties is a large part of the more than $3 billion that Louisiana coastal protection and restoration officials plan to spend from 2021 to 2023 on habitat restoration efforts that will improve the state’s fishing and hunting opportunities and protect coastal communities.

PROJECTS

This report focuses on four major projects built or planned using Deepwater Horizon penalties that have directly benefited anglers and hunters by improving coastal habitats.

All totaled, they represent an investment of more than $600 million in making Louisiana’s “Sportsman’s Paradise” a world-class hunting and fishing destination for decades to come.

Caminada Headlands A.K.A. Elmer’s Island

The restoration of the Caminada Headlands is the largest coastal restoration project in Louisiana and the largest single investment in the recovery of the Gulf Coast after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Known by locals as Elmer’s Island and Fourchon Beach, the Caminada Headlands is a 13-mile stretch of beaches, dunes, and marsh that extends from the mouth of Bayou Lafourche—called Belle Pass—all the way to Caminada Pass on the western tip of Grand Isle. This habitat was restored in two phases over five years using a combination of $145.9 million in oil spill fines from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund plus $40 million from the Coastal Impact Assistance Program and $30 million in state budget surpluses.

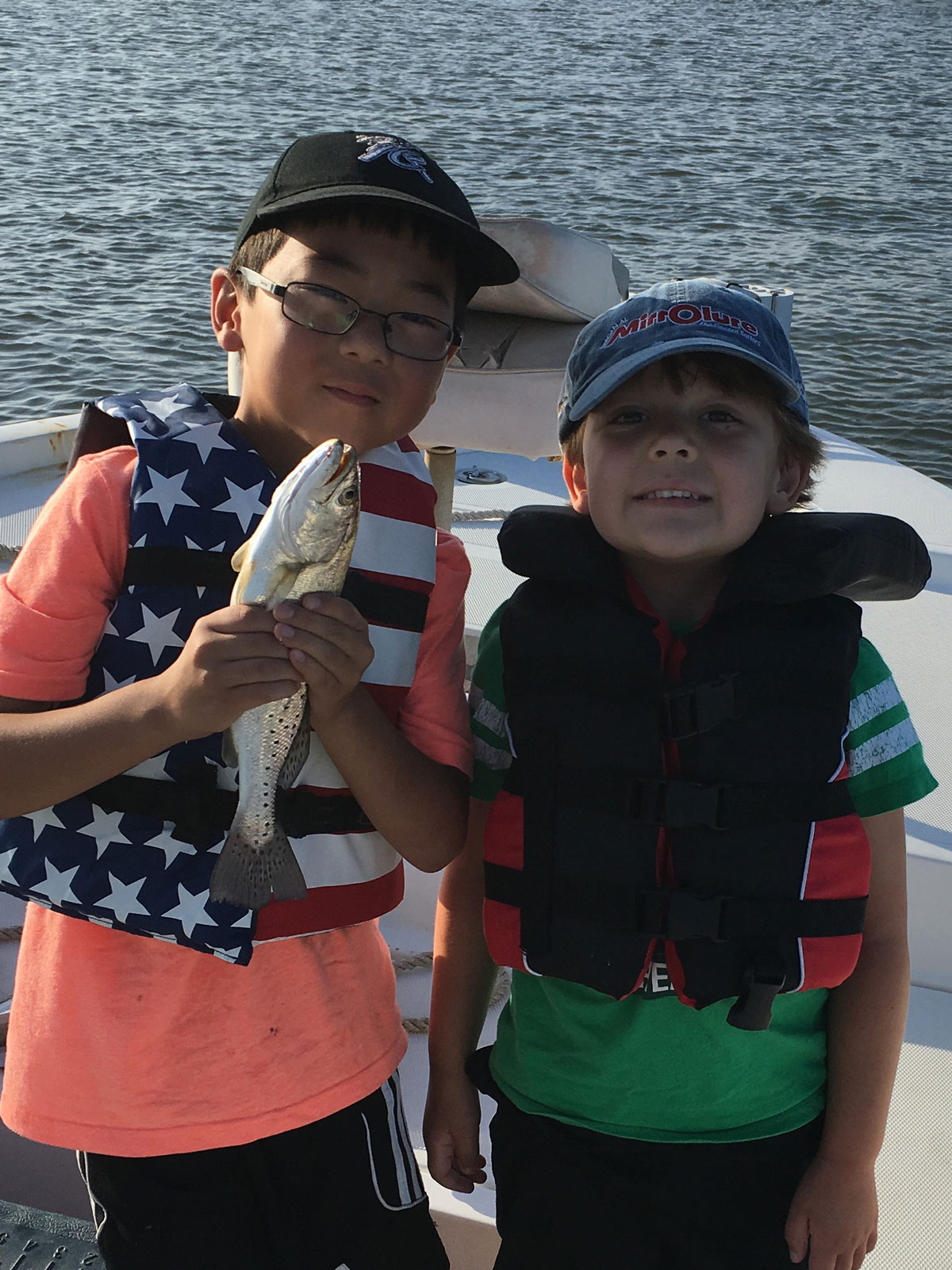

Without question, Caminada is Louisiana’s most popular summertime fishing destination. Its proximity to Grand Isle—Louisiana’s only inhabited barrier island—and Port Fourchon—one of the Gulf’s most popular angling jumping-off spots—means hundreds of thousands of anglers, crabbers, and beach combers visit Elmer’s and the Fourchon each year. The area is also home to Elmer’s Island Wildlife Refuge, a public recreation area overseen by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, which is popular among anglers and bird watchers.

For the last century, hurricanes, strong winter storms, subsidence, and tidal currents have eaten away at the headland, causing the beach to retreat about 35 feet per year. These conditions threaten the more fragile marshes to its north, not to mention the energy infrastructure of Port Fourchon and camps and homes on Grand Isle and the only access road, Highway 1.

In 2010, oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill coated this beach. Many of the iconic pictures circulated in the media coverage of the spill, showing sheets of sticky, rust-colored tar mats and brown pelicans coated with oil, were taken at Elmer’s Island and the Fourchon Beach. Wading wasn’t allowed for more than two years, as heavy equipment and cleaning crews scoured the sand for tar mats.

Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority were back with more heavy equipment and personnel in August 2013, this time to restore the beaches and dunes, rather than drag and sift them for oil. The project used about 8.4 million cubic yards of sand mined from an ancient submerged delta of the Mississippi River to extend the beach 500 feet into the Gulf of Mexico, rebuild dunes up to seven feet tall, and plant those dunes with native vegetation. An additional 200 acres of tidal marsh were rebuilt, as well.

Barges moved the sand from Ship Shoal to a staging area in Belle Pass where it was pumped onto the beach and then shaped with bulldozers. Sand fencing was placed along the beach to help capture wind-blown sand to rebuild dunes as well. By the summer of 2017, Elmer’s was opened completely to wade fishing, restoring a summertime tradition that dates back several generations.

Queen Bess Island

Nearly $19 million in fines from the Natural Resources Damage Assessment have been invested in Queen Bess Island, located just two miles east of Grand Isle in Barataria Bay, to repair decades of erosion and subsidence, as well as oil spill damage. While far smaller in scope compared to the Caminada project, this restoration work has had outsize impacts for anglers and Louisiana’s most iconic bird.

After DDT and other pesticides decimated pelicans in the 1950s and early 1960s, Louisiana was left without a native population of the bird emblazoned on its state flag. In 1971, biologists from Louisiana and Florida worked together to bring 750 young Brown Pelicans to the Barataria Basin, releasing them on Queen Bess, where 11 pairs originally built their nests.

By 2009, there were an estimated 80,000 or more Brown Pelicans in Louisiana and the bird was removed from the Endangered Species list. But only a year later, several thousand pelicans and critical habitat on Queen Bess Island were harmed by the Deepwater Horizon spill.

The island is now home to the largest population of brown pelicans in the Barataria Basin, and nesting habitat has grown from just five acres in the summer of 2019 to 36 acres upon completion of the project in late February 2020.

Queen Bess’s proximity to Grand Isle also means that it is visited by tens of thousands of anglers every year. The Barataria Basin was once dotted with small islands like Queen Bess, the remnants of old headlands and bayou banks once connected to the Mississippi River that erosion and subsidence has wiped from the landscape. This has meant less land to dampen waves and protect fish and fishermen, making the island even more important to anglers.

Construction for the Queen Bess project was compressed into a six-month period from late summer 2019 to late February 2020 to avoid interfering with pelican nesting season. It included ringing the island with limestone chunks up to three feet above sea level to give it additional capacity to withstand wave action, subsidence, and sea-level rise.

Rock breakwaters were also built on the southwest shoreline to provide calm water areas for pelicans and other birds. Then, more than 150,000 cubic yards of sediment dredged from the Mississippi River was transported about 25 miles to the island on barges. After the sediment was shaped by bulldozers, tidal sloughs were constructed to allow some water flow into the island and native vegetation was planted to enhance habitat and fight erosion.

The restoration project is expected to extend the life of the island for more than three decades, allowing brown pelicans to thrive where anglers can chase speckled trout, redfish, and sheepshead for years to come.

Whiskey Island

Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority has invested nearly $500 million in rebuilding more than 60 miles of beaches and barrier islands since 2007. It has also overseen construction of hundreds of acres of back-barrier marshes designed to enhance fisheries habitat and help retain the sand that has been pumped ashore by dredges to rebuild beaches and dunes.

Arguably, the most ambitious of these efforts, completed in 2018, is the restoration of the Caillou Lake Headlands in Terrebonne Parish, commonly known as Whiskey Island. It is one of three barrier islands that once comprised Isle Derniers, a massive 25-mile-long island that has been eaten away and fragmented over the last century by hurricanes and subsidence.

For more than a year, sand was pumped 10 miles to the island by a dredge from Ship Shoal, the massive sand deposit on the Gulf floor that also contributed to the restoration of Elmer’s Island. Gradually built up by the Mississippi River about 7,000 years ago, Ship Shoal will be tapped again in 2020 and 2021 for projects at West Belle Pass, Timbalier Island, and Trinity Island, which is immediately east of Whiskey Island.

All four projects are addressing the weaknesses in the barrier island shorelines of the Terrebonne Basin, fortifying protections for coastal communities and sustaining critical fish and wildlife habitat—all using funding from oil spill penalties.

The $117-million project at Whiskey Island has restored 1,000 acres of beaches and dunes and established another 160 acres of marsh platform. This builds upon the success of a 2009 project that created 300 acres of marsh on the island’s east end.

Anglers are particularly fortunate that Whiskey Island’s beaches and marshes, coated and stained by oil in 2010, have been renewed. The effort has helped to sustain and even enhance Terrebonne’s rich recreational and commercial fisheries and give coastal birds—like the brown pelican populations hit hard by the spill—a place to nest and feed for at least two more decades.

The project also demonstrates the broader scale of Louisiana’s coastal restoration efforts now that oil spill dollars have become available. Past barrier-island restoration efforts were pieced together over a decade or more. But with oil spill penalties committed by Louisiana and federal resource agencies like NOAA and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, larger and more comprehensive projects can be built all at once. This ultimately saves money and makes for a more resilient and productive island.

Without the consistent, and now increased, investment in the restoration of Terrebonne Parish’s barrier islands over the last 30 years, it’s likely those islands would be little more than sandbars and submerged humps today, instead of continuing to be fish and bird meccas and the first-line of defense against hurricanes.

Mississippi River Reintroduction at Maurepas Swamp

Looking ahead, the restoration of Maurepas Swamp is a unique opportunity for the CPRA to expand coastal habitat restoration and sustainability projects beyond rebuilding coastal marshes and barrier islands.

Maurepas Swamp is a massive area of old-growth cypress-tupelo swamp nestled between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that separates Lake Maurepas from the Mississippi River. The swamp was once connected to areas that were flooded annually by the Mississippi, but it was isolated by levees more than a century ago. The natural hydrology of the swamp has also been interrupted by roadbeds and spoil banks from oil and gas canals.

Without the annual floods from the Mississippi River allowing sheet water to flow over the swamp, the native trees have lost a vital source of nutrients and the fish and wildlife have suffered. What could be a great area for largemouth bass, catfish, crawfish, and crappies—what the locals call sac a lait—is only a marginal fishery that has declined steadily over the last half century.

Broad areas of low-oxygen water filled with invasive vegetation, like water hyacinth and Salvinia, have replaced healthy swamps full of native submerged vegetation and the oxygen-rich water needed to support healthy fisheries. The Salvinia has also hampered what was once a world-class duck hunting area.

To bring back some of the nutrients and increase water health, in 2022 the CPRA is planning to begin construction of a structure on the Mississippi River that will allow for a relatively small but vastly important flow of water at 2,000 cubic feet per second through the swamp. Approximately 45,000 acres of imperiled swamp will slowly come back to life, limiting the saltwater intrusion brought by hurricanes and improving fisheries. Hopefully, a boost to waterfowl hunting and migratory and native wildlife habitat will follow.

The bulk of the funding is coming from the RESTORE Council, a federal-state collaboration created by the 2012 law of the same name, which committed 80 percent of oil spill penalties back to the Gulf States to address habitat and economic damages. In February 2020, the RESTORE Council granted Louisiana $130 million for the Maurepas project, and state officials are working to secure another $70 million in oil spill penalties, as well.

An added benefit for sportsmen and women is that much of the positive impacts will be on public land managed by Louisiana’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. The Maurepas Swamp Wildlife Management Area is a massive 122,000-acre public hunting and fishing area, much of which is located within the diversion’s area of influence. A 2013 settlement between MOEX, one of the owners of the Deepwater Horizon’s Macondo Well, and the U.S. Justice Department provided Louisiana with $6.75 million to add 11,145 acres to the WMA to preserve the coastal cypress-tupelo forest.

Improving the health of the swamp will also increase its ability to help protect adjacent communities from hurricane winds and storm surges. The swamp stores storm surge waters during hurricanes. The diversion can operate post-storm to push out higher salinity water and protect the trees and fish from long-term damage. The trees also help to dampen wind, further protecting communities.

In all, the conservation of Maurepas Swamp using the restorative power of the Mississippi River may prove to be one of the wisest investments of oil spill penalties thus far, especially given the long-term benefits to hunters, anglers, and local communities. Allowing the swamp to continue to degrade would jeopardize the cultural value of fishing and hunting in the area and leave numerous towns in Southeast Louisiana more vulnerable to future hurricanes.

Feature photo by Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Nice to read factual information