Upgrading wire fences with help from landowners and volunteers aids animal movement across the West

A video we posted on Instagram recently showed that just a single strand of barbed wire on a dilapidated fence was enough to stymie a six-point bull elk as it attempted to pass through. The bull hit the wire with his right front hoof, pulled his leg back, and got slightly startled at being tangled, but it managed to step away from the fence.

I’m pretty sure that old fence didn’t harm the bull or ultimately impede him getting to wherever he was going, but this is not always the case. Many of us have witnessed deer, elk, and pronghorn antelope nervously walking up and down a fence line or, worse yet, tangled up in a fence either dead or left to die. This also is a habitat connectivity issue—one that can create additional challenges for big game in areas where their migration routes are already fragmented by roads and other obstacles.

Wild critters frustrate many landowners by damaging fences, creating the extra work of mending them so that livestock does not escape. But there are alternatives for making fences more friendly to wildlife.

Barbed and Beyond

When asked about innovations of the 19th century, few people would likely name barbed wire, but its invention changed the American West almost overnight—and it has had consequences for wildlife ever since.

After the Civil War, Western rangelands were homesteaded and settled, but landowners needed a way to keep livestock within their property boundaries. This technology essentially ended the “open range” grazing era and changed the West forever.

Barbed wire is perhaps the most pervasive option in big game country, but of course it’s not the only style of fence with impacts for migrating animals. Woven wire fences are almost impossible for wildlife to pass through. When these are combined with a barbed top wire, it is a lethal and impenetrable combination considered the most detrimental to wildlife.

What Happens to Wildlife?

There are several rather obvious impacts of fencing on wildlife worth mentioning. First, our big game animals—like mule deer, pronghorns, and elk—did not evolve with fences across once open spaces, so traditional migration corridors of these animals have been interrupted and altered.

But animals can just jump over fences, right? Well, yes, or go under them. And most critters can clear a fence without issue. But many animals become entangled and die from either starvation, dehydration, hypothermia, or predation. Juveniles are especially vulnerable and make up a large percentage of big game animals killed by fences. Animals with horns or antlers sometimes get their headgear tangled up in fencing, and their fate may be the same as if they’d attempted to jump a fence.

It’s not just existing fencing that can cause trouble—dilapidated fences that are no longer being monitored, used, or maintained can be a real danger to critters, too.

According to the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Department’s “Fencing with Wildlife in Mind” brochure, fences incompatible with wildlife are those that:

- Are too high to jump.

- Are too low to crawl under.

- Have wires spaced too close together.

- Have wires that are too loose.

- Are difficult for fleeing animals to see.

- Create a complete movement barrier.

Where Fencing Works for Wildlife

On the other hand, strategically placed fencing can sometimes be a good thing for big game animals, because it funnels them to safety. One of the three most critical factors involved with placing an effective wildlife crossing over or under a roadway is to ensure that fencing guides the animals to the structure.

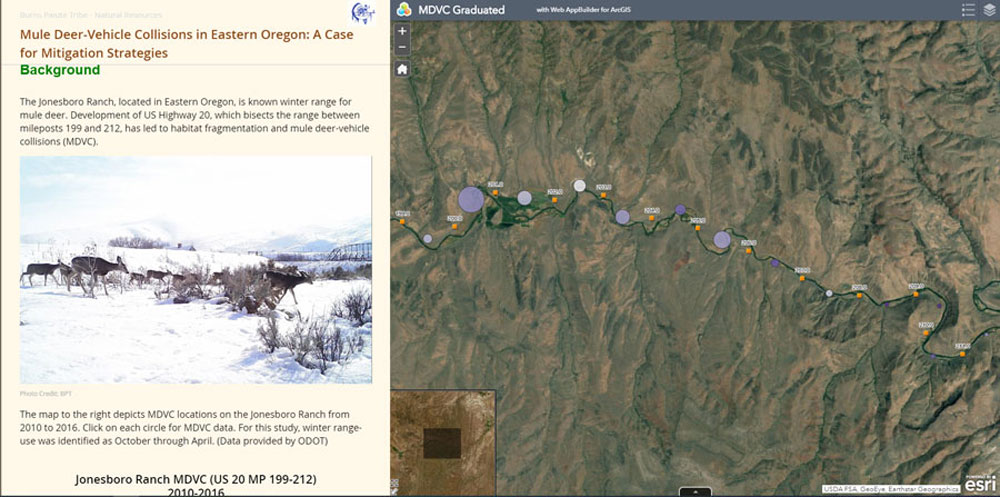

The Arizona Game and Fish Department found this out firsthand by retrofitting the fencing at an older and ineffective crossing structure on Interstate 17. Prior to the retrofit fencing project, an average of 20 elk per year collided with vehicles. After adequate fencing was installed, there was a whopping 97-percent reduction in vehicle collisions with elk.

Often, game-proof fencing, which is typically 8 feet or taller and made of woven wire, is needed to reduce damage to certain crops or other property. Such exclusion fences reduce unnecessary conflicts with humans and the need for damage control of problem animals or populations.

Mending Fences

Most state and federal agencies have guidelines for wildlife-compatible fencing, and there is certainly no shortage of recommendations available. Wildlife-friendly options should have:

- A smooth wire at the top no higher than 42 inches from the ground—on steep slopes, pinpointing where the animal would leap from helps to determine the effective fence height.

- A smooth wire at the bottom at least 18 inches above the ground.

- Built with no stays on the fence and posts at least 16 feet apart.

Many landowners have stepped up to help solve fencing problems for wildlife. Ruben Vasquez, a district conservationist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service in Wyoming, wrote about ranchers who realized that existing five- or six-wire barbed and woven wire fences prevented pronghorns, elk, and deer from moving freely across their lands. It was also expensive to continually repair fences damaged by wildlife attempting to cross.

With help from the Farm Bill’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program, many landowners have been able to replace their existing fences with more wildlife-friendly versions, and this is a win-win. In 2017, Vasquez reported that 29,000 feet, or roughly five and a half miles, of problem fences were replaced with wildlife-friendly fence on just one Wyoming ranch.

Landowners can also leave certain gates open or sections of fence where wildlife readily cross during their seasonal migrations. The key, of course, is knowing precisely when and where animals move and encounter the fences. But this is a good tactic to help facilitate seasonal movements across private lands during predictable time periods.

Getting to the Other Side

Of course, there can never be too much of a good thing, and thousands of miles of dangerous fencing remains across our landscapes. Federal land management agencies need to prioritize retrofitting incompatible fences that threaten wildlife across our public lands. Landowners are doing great work to help make fences wildlife-friendly, but more resources and technical support would help expand these efforts.

Adequate, long-term funding for Farm Bill conservation programs like EQIP and other resources will be needed to help retrofit unsafe fences across the West. But volunteers can help too. Old fences need to be pulled off the land either simply to remove the hazard or before new, safer fences can be installed.

In many areas, fence removal and replacement projects can be easily tackled by conservation volunteers in an afternoon or two. Others may take more time, resources, and skilled labor to complete, but projects like this help sportsmen and women get more involved in conservation and thinking about how game species use habitat on a landscape scale. Where migration corridors are fragmented and interrupted by development and other threats, installing the right fence can be a small price to pay to help knit together these important travel routes.

Top photo by Idaho Game and Fish Department.

Yes, this is great. My wife, Christine Paige, was involved in writing and editing some of the first state guides to wildlife friendly fences. She wondered at the time if the effort (and making a few thousand dollars) were going to actually make any difference. Now that the issue has been embraced by many organizations (some government agencies took a little more prompting than others) she continues to see the expansion of wildlife friendly fences continue to grow. As you said, there are still thousands of miles of poor fence, poor fence designs still getting built and unending education to go. But progress continues to be made – thanks for helping to spread the word.

Please start building overpasses and underpasses (bridges) for the animals. By fixing wire fencing is not the safest alternative to use. Too many animals have been killed by the wire fencing or once over the wire fencing, there is a possibility the animals can get killed by fast moving vehicles. Please start thinking about the overpasses and underpasses (bridges) for animals.

I love this and always hated fences this is great

Thanks for writing about making fences friendlier for wildlife! I’ve been working on this issue for 12+ years, and wrote the wildlife friendly fence handbooks for Montana, Wyoming, and Alberta, which many other states have used as a foundation for their own guides. It is incredibly gratifying to see the paradigm shift in the last decade — landholders and land managers across western North America and beyond are re-thinking how we use the landscape, and are removing and modifying fences to create easier passage for wildlife. There are dozens of possible solutions for different situations. You can download a PDF of the second edition of the Wyoming Landowner’s Handbook to Fences and Wildlife here: https://wgfd.wyo.gov/WGFD/media/content/PDF/Habitat/Habitat%20Information/Grazing%20Management%20and%20Prescribed%20Burning/A-Wyoming-Landowner-s-Handbook-to-Fences-and-Wildlife_2nd-Edition_-lo-res.pdf