These programs could serve as a model for other states with a growing tally of landlocked hunting and fishing areas

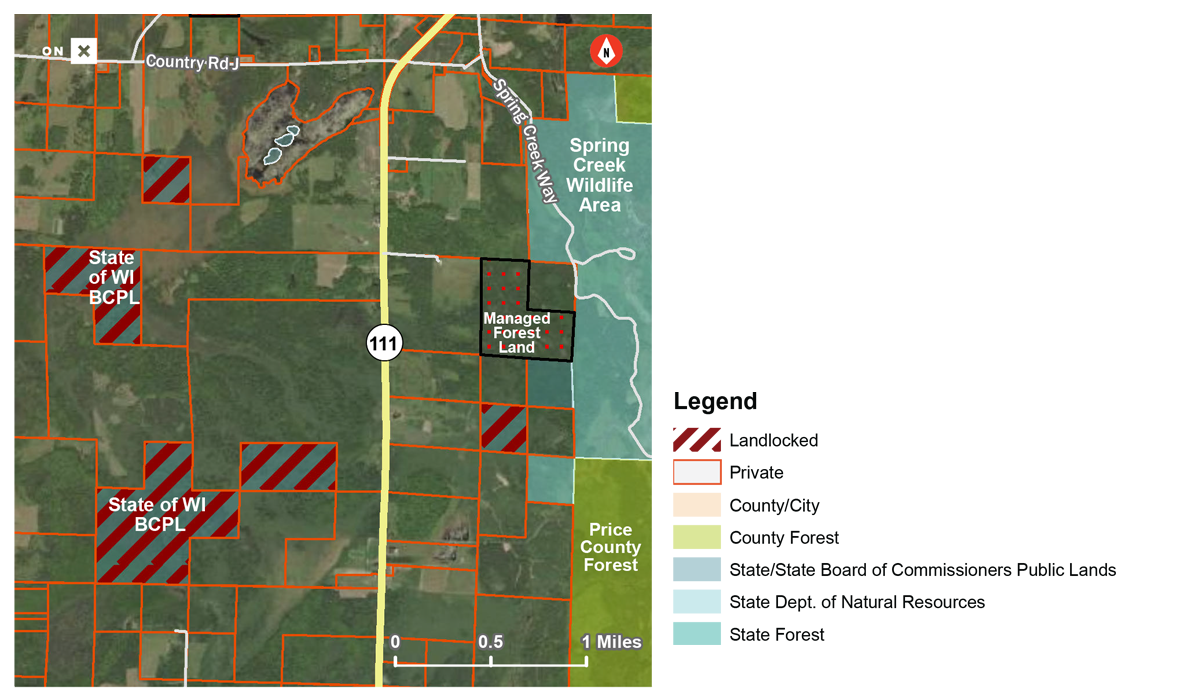

These days, thanks to GPS technology, anyone with a smartphone can take advantage of the hunting and fishing opportunities offered by even the smallest parcel of public lands. But what if you stumble across something like this, where there doesn’t seem to be any legal access to reach it?

You might think it’s a mistake, but there are actually more than 300,000 acres of these landlocked public lands in Minnesota and Wisconsin alone. Across the West, there are nearly 16 million landlocked acres.

Sure, you could knock on a few doors and request permission to cross private land into those crosshatched areas. But if access to public lands like these remains exclusive or temporary, we’re tying one hand behind our backs when it comes to recruiting and retaining the participation of new hunters and anglers.

For a Midwestern hunter looking to hang a treestand for whitetails, set up an ambush for turkeys, or work a woodlot for grouse—especially for the first time—a small or overlooked public parcel could be a game-changer. And easy access to a lake shore or riverbank might give a parent the only place they’re be able to teach their kids to fish for walleye, pike, or smallmouth bass.

Strategically unlocking as little as a few dozen inaccessible acres at a time could mean the difference between a young person having a place to hunt or not. A lifelong passion for fishing—and the conservation funding raised by those license purchases—could hang in the balance.

So how are Midwestern states unlocking inaccessible public lands?

Landlocked public lands are best made accessible through cooperative agreements with private landowners that result in land exchanges, acquisitions, and easements, but this critical work cannot be facilitated by land trusts, conservation organizations, and public agencies without funding.

When thinking about opening inaccessible public lands, even small projects can offer big benefits. Here are three programs that support these efforts.

The Land and Water Conservation Fund

The federal LWCF remains the most powerful tool available for establishing and expanding access to public lands and waters. And it just got more powerful, with the recent passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, a bill that fully funds the program at $900 million annually in support of wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation, including $27 million that is dedicated to public access. Importantly, the LWCF is not just limited to federal projects—at least 40 percent of the program must be used for state-driven projects, making it available to help open state- and county-owned lands for public recreation.

Minnesota’s Lessard Sams Outdoor Heritage Fund

Established by the voters of Minnesota in 2008, the Outdoor Heritage Fund is supported through the state sales tax. This program empowers projects that protect, enhance, or restore prairies, wetlands, forests, or other habitat, and—when it meets those primary goals—can also be used to open or expand access to inaccessible wildlife management areas managed by Minnesota DNR’s Fish and Wildlife Division. With an estimated $100 million available in 2022, the Outdoor Heritage Fund is a heavy hitter in support of conservation and access.

Wisconsin’s Knowles Nelson Stewardship Program

Created in 1989, this program exists to preserve valuable natural areas and wildlife habitat, protect water quality and fisheries, and expand opportunities for outdoor recreation. With a budget of $33 million in 2019, Knowles Nelson is a major program that, among other things, can help unlock Wisconsin’s state parks, wildlife and fisheries areas and state natural areas. Knowles Nelson is set to expire in 2022 and will need to be renewed by the state legislature. State decision makers need to know the importance of this program for wildlife habitat and public access.

What Sportsmen and Women Can Do

Both Minnesota and Wisconsin have innovative state programs for conserving habitat and improving access that should serve as valuable models for other states looking to do the same. Support local ballot initiatives and state legislation to set aside these dedicated funds where you live.

To dig into the data we’ve uncovered on inaccessible public lands across the country, click here.

I absolutely want to know about landlocked land that my tax dollars are supporting but I am blocked from using. These areas appear to amount to public lands held accessible only to those that border it, perhaps intentionally setup this way.

Are you familiar with public footpaths in the UK? I assume that when speaking about access it is by automobile. I wonder if private property owners might be more open to the idea of a footpath. In the UK, the farmer (for instance) must mow or not plant in a registered public footpath. Many public paths are hundreds of years old. This might be a more amenable way to entice landowners to consider an easement if no motors were aloud; much like a small lake.

Hi Kimberly,

That’s a great question. Access easements specify how they can be used and by whom. It is true that we often refer to easements in the context of roads and motor vehicles, but many easements that allow access to public lands restrict use to, for instance, a designated footpath. And you’re absolutely right–there are many situations in which an easement providing non-motorized public access might be more agreeable to a landowner than one that allows for motorized travel.

Thanks!

In NY are national Forest is located on the Delaware River I had friends and campers that were accessing camping zones along the river that can sides with the national Forest and they told me I was trespassing on boy scout property