Legislation that requires federal agencies to digitize their public land access data would help us spend Land and Water Conservation Fund dollars more efficiently

Hunters and anglers are celebrating the passage of the Great American Outdoors Act in the House—and with good reason. Once it is signed by the president, the bill becomes law with major benefits for public land users and habitat.

In addition to providing $1.9 billion annually from 2021 to 2025 for much-needed public land maintenance projects, the Great American Outdoors Act will also secure $900 million annually for the most powerful tool we have to improve public lands habitat and access: the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

In a time of political tension and turmoil, it’s impressive that hunters and anglers are accomplishing so much to benefit our outdoor recreation opportunities. It shows that our issues resonate across party lines and with a broad spectrum of Americans. What would make the LWCF victory even sweeter, however, would be the subsequent passage of the bipartisan Modernizing Access to our Public Land, or MAPLand, Act later this year.

Here is why this legislation effectively super-charges the impacts of the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

More Than the Minimum for Access

Utilizing receipts from offshore oil and gas development, the Land and Water Conservation Fund is designed to support conservation and outdoor recreation. In 2019, the fund was permanently reauthorized with the passage of S.47—the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act. A provision was included in that legislation requiring that three percent of the total, or a minimum of $15 million, be used each year to establish or improve access to public lands.

With passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, the public access provision increases to $27 million annually.

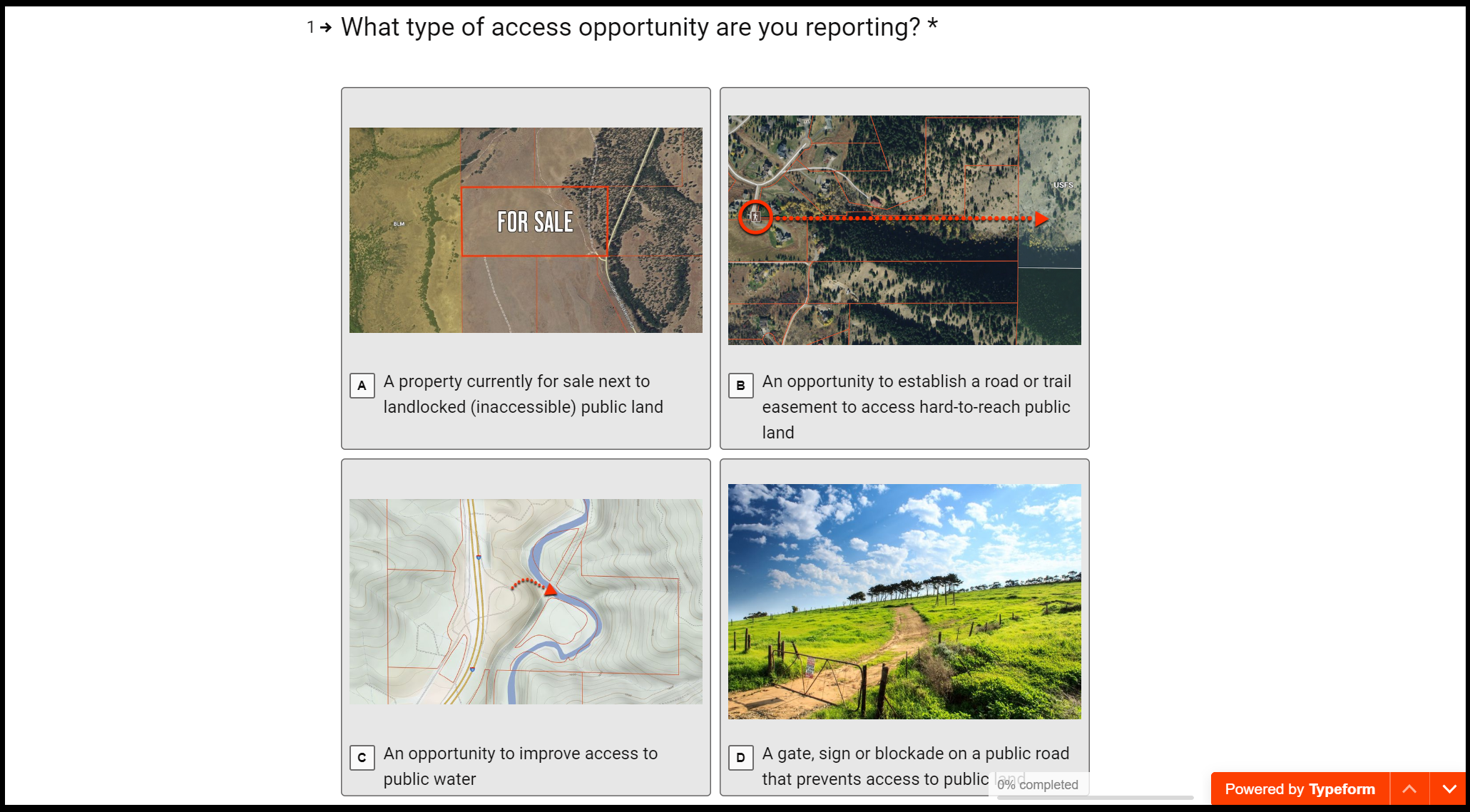

This access money is being made available because members of Congress realize that many public lands are landlocked and completely inaccessible or difficult to access. You may recall that over the last three years the TRCP has teamed up with onX to study and address this very problem. So far, we’ve found that 15.86 million acres of state and federal lands are landlocked across 13 Western states.

Landlocked public lands can be found in other regions of the U.S., as well. (More on that from us very soon!)

Having resources available through LWCF will be critical in addressing access challenges across the nation in the coming decades. Right now, there are commendable access projects being completed by land trusts and the federal agencies each year, however, these access dollars could be used even more strategically if everyone had a precise understanding of where public access routes exist and where they do not.

This is where the MAPLand Act comes in.

Welcome to the Digital Age

Over the past century, federal land management agencies—including the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management—have actively acquired access easements and established public roads and trails across private lands to unlock inaccessible public lands. These easements or “rights of way” constitute a permanent access right that is controlled by these federal agencies.

However, many of the agencies’ access easement records are still held on paper files at local offices and cannot be integrated into digital mapping systems that allow hunters and anglers to see where public access has been secured.

The U.S. Forest Service alone has an estimated 37,000 recorded easements, but only 5,000 have been digitized and uploaded into its electronic database.

If federal land management agencies are going to make the most of the $27 million in annual access dollars they will receive through a fully funded Land and Water Conservation Fund, they must digitize their access easements. Otherwise, they will not be able to efficiently see where they hold access across private lands or effectively prioritize future access acquisitions.

Truly Creating Access for All

Fortunately, the MAPLand Act would fix this challenge by providing resources and direction so that federal land management agencies can digitize their access easements within a three-year period and make that information available to the public.

When completed, everyone will easily be able to see where permanent public access has already been secured and where it has not, informing future land acquisition projects. This will also help the recreating public to understand where they have a legal right to use a road or trail and where they need to secure permission from a private landowner.

In addition, the MAPLand Act would require that rules related to recreational access on our public lands and waters is standardized and made available digitally. This would mean that smartphone applications and digital mapping systems, like onX Hunt, could reliably point to seasonal allowances and restrictions for vehicle use on public roads and trails, boundaries of areas where hunting or recreational shooting is regulated or closed, and portions of rivers and lakes on federal land that are closed to entry, closed to watercraft, or have horsepower limitations for watercraft.

Now that Congress has passed the Great American Outdoors Act and permanently committed to the maximum funding LWCF was meant to have, sportsmen and women need one more thing: Swift passage of the MAPLand Act to ensure that available access dollars can be used as effectively as possible to help you access your public lands.

Take action today to get your lawmakers on board.

Top photo by John Fowler via flickr.

I support your efforts fully

This would help make all of our public land accessible.

I’d also like to see funding dedicated to promote legislation at the state level making all creeks public as is done in Montana and elsewhere. Also requiring access to public lands vial the shortest distance. Like a 30 foot easement saving a 4 mile walk around. Ballot measures just like what was done to us with wolves.