In the last decade, more and more Farm Bill dollars have been invested to enhance habitat and watersheds through creative partnerships on landscape-scale projects, and TRCP partners are some of the most prolific collaborators

With approximately $5 billion a year in conservation funding to invest across nearly 70 percent of our country’s land mass, conservation programs in the Farm Bill affect all of us who hunt and fish on or near private lands. Many of these initiatives help landowners improve hunting and fishing conditions acre by acre and problem by problem, from boosting wildlife habitat to overhauling water quality and soil health.

The current Farm Bill is set to expire in September 2018, and our community has recommendations for ways to tactically improve the conservation section of this massive legislation. Some have to do with supporting a recent trend: Increasingly, the unprecedented restoration of iconic watersheds and ecosystems is being achieved collaboratively among conservation groups, government agencies, private landowners, and even universities and private companies.

Conserving Better Together

These partnerships are changing the face of conservation and growing a restoration economy that can benefit not only farmers and sportsmen but entire communities. Notable examples are in places with longstanding conservation challenges, like the Chesapeake Bay, Colorado River, Great Lakes, Everglades, Mississippi River Basin, Prairie Pothole Region, Puget Sound, and the longleaf pines of the Southeast. Millions of people live in these watersheds, and they offer significant opportunities to hunt and fish.

We’re especially proud to have many of the partners in our 24-member Agriculture and Wildlife Working Group at the helm of these locally led efforts, which look very different from place to place.

In the Driftless Area of lower Wisconsin, for example, Trout Unlimited is helping landowners restore streams a dozen miles at a time on farmland to improve overall water quality downstream—this has resulted in a billion-dollar economic boost to the region. To similarly reduce nutrient runoff into waterways, the Nature Conservancy has partnered with agribusinesses to sell conservation to farmers in the Great Lakes region. Meanwhile, local land trusts in Central Florida work with ranchers to protect the headwaters of the Everglades from overuse by cattle and improve water flows downstream. Joining forces at a local level is making a big difference for these watersheds.

These landscapes are literally changing with rapid improvements for wildlife, water, and the climate. Wildlife Mississippi has helped restore and permanently protect more than 700,000 acres of forest and wetland habitat, benefiting local communities, waterfowl, and threatened species, such as the Louisiana black bear. Ducks Unlimited works with rice growers to create long-term benefits for waterfowl and wetland health while improving working lands. And the National Wildlife Federation is working with ranchers to create mesic habitat, such as beaver ponds, to restore scarce water reserves and create vital habitat for wildlife.

From Local to Landscape

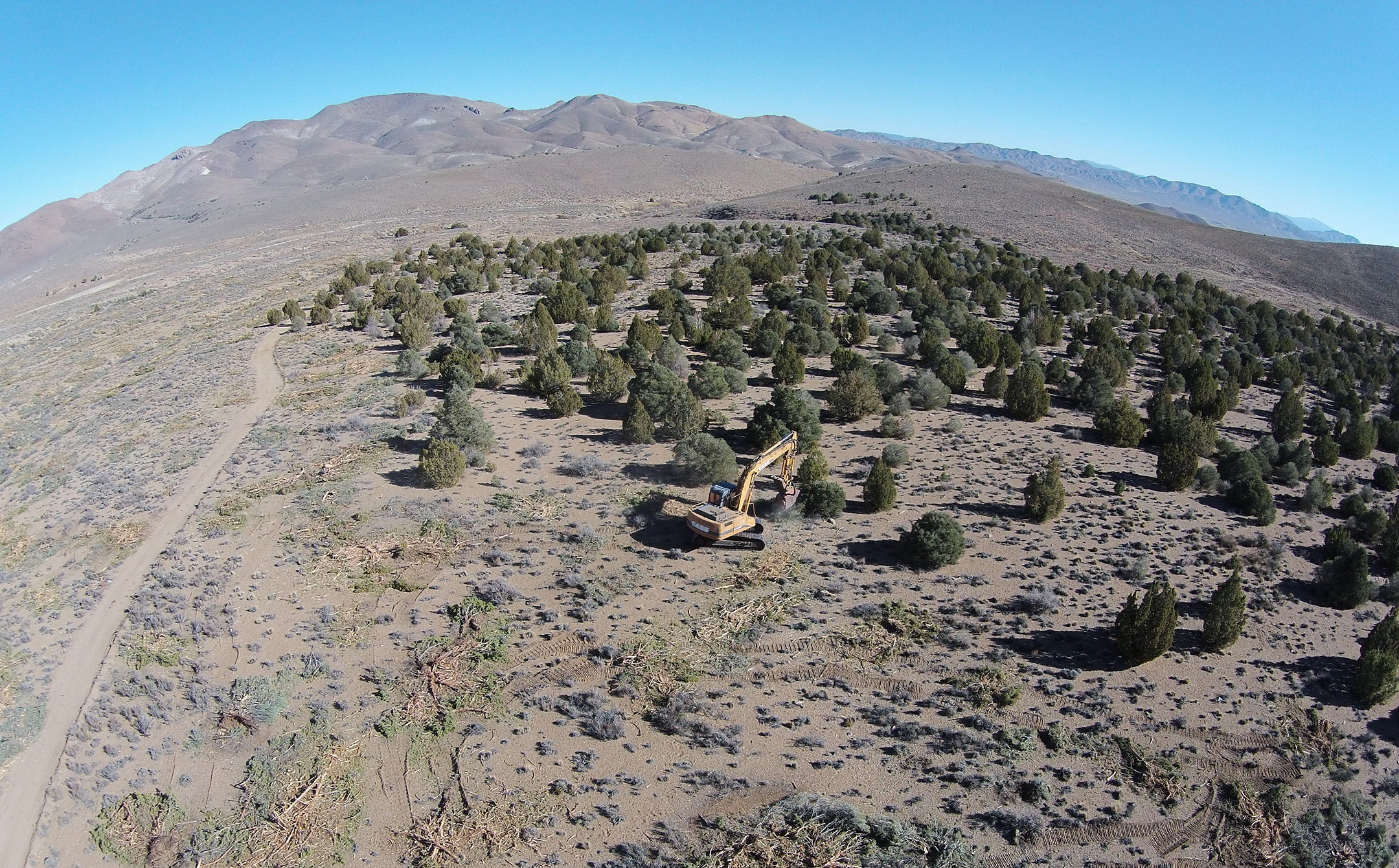

For perspective, many of these kinds of strategic partnerships, which create more valuable conservation outcomes, have only come together in the past decade or so. As a conservation community, we are just learning how to create a larger restoration economy by working in concert to chip away at discrete problems. There’s a new Farm Bill every five years, and over the past couple of iterations we have moved from random acts of conservation to strategic and well-prioritized efforts for the benefit of entire communities—from those of us who like to hunt and fish to those who just happen to live downstream.

This is something we can only achieve by working together. Since the 2014 Farm Bill, hundreds of new partnerships have formed within iconic landscapes and watersheds, and there are some positive ways that this kind of collaboration can be encouraged and empowered in the next bill.

As everyone from NGOs to local water district managers are learning how to be more effective at meeting conservation challenges and work with a greater variety of people and landowners to craft solutions, we want to see a Farm Bill that will make more of these kinds of efforts possible by supporting smart collaboration. Simply put, efforts like these and more across all parts of our country get more hands involved in conservation so that we can continue to meet our growing challenges.

Chris Adamo is a Farm Bill conservation consultant for the TRCP. Adamo helped lead the effort for the last farm bill as staff director of the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee under Senator Stabenow and is currently a senior fellow at National Wildlife Federation.

As we all know money drives most issues, therefore we must stress to the powers making decisions about the farm bill that conservation programs drive local economies.

The future of the ring necked pheasant lies with the 2018 Farmbill, and the CRP acreage therein. It’s that simple. Ask South Dakota small businesses how important this resource is to their economy!