This holiday season, we’re toasting to the success of our partners who are working together to build a better future for sagebrush habitat and #350species

With a quick glance across the West, it’s clear why cooperation is a cornerstone of conservation. This is the region where multi-generational ranching families move cattle, sportsmen and women pursue trophy elk and cutthroat trout, energy and timber companies extract resources, and outdoor enthusiasts climb peaks, bike single tracks, and explore some of our nation’s largest networks of public lands.

This rich diversity of demands on the land increases the pressure to conserve sagebrush habitat and the 350 species that depend on it. In recent years, an unprecedented effort to conserve the sagebrush ecosystem—which is home to iconic species like greater sage grouse, mule deer, and pronghorn antelope—brought together conservationists, ranchers, energy developers, federal and state agencies, local governments, and outdoor recreation businesses in a landmark victory for effective collaboration.

But because administrative action to not list a species doesn’t remove trees, plant sage, and improve habitat in and of itself, a policy win for sage grouse is only half the battle. It’s our partners who are at the forefront of on-the-ground conservation work, ensuring that habitat remains intact, energy development and grazing practices are done wisely, and sage grouse ultimately remain free of the threat of an Endangered Species Act listing for years to come.

As folks come together with friends and relatives this holiday season, we’re thinking about our family—the network of fine conservation groups that unite over wildlife, habitat, and our hunting and fishing traditions—and how working together is better than working alone, especially in sagebrush country. Here’s some of what they have accomplished.

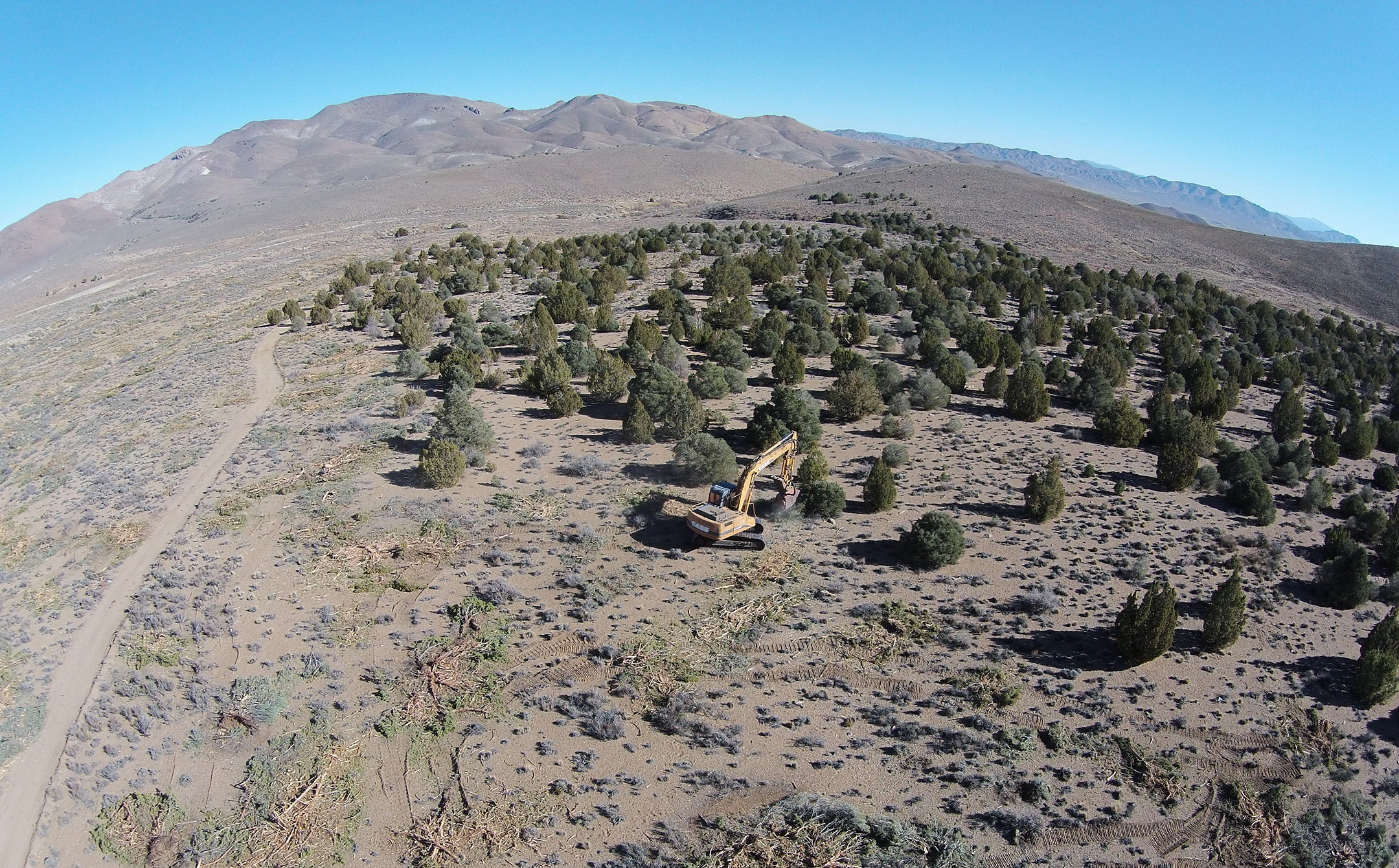

The Removal Squad

In sage grouse country, Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever have embarked on a mission to improve sagebrush habitat by treating areas of encroaching Utah juniper. This thirsty tree has invaded the sagebrush landscape and built up heavily wooded areas that can’t support sage-dependent species. Working with the Sage Grouse Initiative, PF has helped treat approximately 14,000 public acres, with another 12,000 scheduled for treatment over the next two years. That’s in addition to ongoing treatments underway on other state and private lands adjacent to the project.

The scale of the project is huge, especially considering all the organizations that must work together to gather the necessary land access, scientific expertise, and manpower, including local offices of the Bureau of Land Management, Natural Resources Conservation Service, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, plus state wildlife agencies, conservation districts, local working groups, permit holders, and private landowners.

It’s a testament to how much can be accomplished by working together. Partnerships have enabled more on-the-ground success than any one individual group could have accomplished on its own, and this has allowed improvement of sage grouse habitat across fence lines, regardless of ownership.

The Big Game Boosters

Improving conditions for one species creates benefits for many others (one of the reasons conservationists are so obsessed with quality habitat), and that’s where the Mule Deer Foundation comes in. Muleys and sage grouse have the same habitat needs in many areas, especially on winter ranges, so responsible management of grazing and conservation of critical wintering areas benefits both species.

Throughout their range, mule deer populations are stagnant or declining, largely due to loss and fragmentation of habitat. In order to improve and restore mule deer habitat at an unprecedented level, MDF is working across sage grouse country in close coordination with (you guessed it!) partners. A 2014 study actually demonstrated that measures taken to conserve sage grouse in Wyoming also benefit mule deer migration routes, and it highlighted the role of state and federal agencies and NGOs working together.

Among agencies, tools like targeted easements on private lands and limitations of disturbance on federal lands can proactively conserve remaining migration corridors, stopover habitat, and winter ranges for mule deer. Included in those protective measures is the state of Wyoming’s sage grouse “core area” policy, which limits development in the state’s key grouse habitat, as well as conservation easements and agreements with private landowners to limit development.

To complement MDF’s existing habitat restoration program, the Natural Resource Conservation Service and the Sage Grouse Initiative have come on board to enable greater private landowner cooperation. With a substantial portion of mule deer winter range occurring on private land throughout the West, this partnership has enabled more conservation success than MDF could have achieved on its own.

The Conveners

The Wildlife Management Institute has lent their leadership and science expertise to the sage grouse conservation effort through the annual WMI North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. In our circles, we refer to this conference as simply “the North American,” and the fact that it is so widely recognized is a testament to how many people WMI has reached.

For several years now, the North American has included sessions on sage grouse to highlight and expand upon efforts by WMI, state fish and wildlife agencies, and partners to advance conservation. Together, we have an opportunity to address some of the toughest issues affecting sage grouse country, and getting together in the same room helps us to forge important connections and trade ideas.

The Solution-Oriented Seeders

The Nature Conservancy has been working to protect sage grouse by improving and expanding current conservation efforts across the sage-steppe ecosystem, not only for the iconic bird, but also to protect families and communities in the West. Along with partners like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, they’re innovating new techniques for sagebrush seeding and planting in priority landscapes, and collaborating with private landowners to drive forward on-the-ground action.

With restoration work so dependent on sagebrush itself, TNC believes better seeding and planting techniques will ensure better success rates for the plants and wildlife. Plus, improved methods are in the American taxpayer’s best interests, as hundreds of millions of federal dollars have been spent to restore sagebrush habitat with a very low success rate.

So, obviously, the solution is Italian food. The Conservancy’s Oregon chapter has discovered an innovative approach that uses industrial-grade pasta machines to efficiently create packets of sagebrush seeds. The seed blend improves germination by creating a microclimate and lends a “power in numbers” approach, increasing the number of seeds that can break through the dry, hard soil. This work is just hitting the ground in Oregon, but TNC staff and partners are already looking at ways they can expand these efforts in places with similar challenges.

Meanwhile in northwestern Utah, a joint collaboration with five ranching families and NRCS has secured $3.7 million in public funding to protect 9,312 acres of sage-grouse habitat. One of the families involved, the Tanners, has received awards from the National Cattlemen’s Association and the Sand County Foundation for their leadership and work to conserve sage grouse and other wildlife. The Conservancy’s efforts to restore sagebrush habitat and increase sage-grouse populations would not be possible without this kind of collaboration with local landowners.

The Grouse Specialists

Grouse habitat encompasses millions of acres of private and public land. These magnificent birds function as primary indicator species for the health of their particular habitats, and they are held in especially high esteem by sportsmen and women, birders, biologists, and land managers. The North American Grouse Partnership works to bring the plight of all declining grouse species and habitats to the attention of the public, provides oversight for the health of grouse populations, implements solutions to the problems causing grouse declines, and encourages public policies and management decisions that will enhance important habitats and grouse populations.