With participation in hunting declining, an important source of conservation funding is also at risk—unless we can invest more in recruiting the next generation of sportsmen and women

Did you know that every year, hunters contribute more than $700 million to state wildlife conservation efforts? That’s right—for more than 80 years, sportsmen and women have been overwhelmingly responsible for the health of fish and wildlife populations in America.

At the start of the 20th century, several wildlife species were imperiled, with few safeguards in place for dwindling populations. Recognizing that inaction may result in not only the mass extinction of America’s wildlife but also our pursuit of wildlife, hunters decided to take matters into our own hands.

In 1937, with support from the nation’s earliest sportsmen’s organizations, Congress passed the Pittman-Robertson Act, which created the Wildlife Restoration program. Since then, more than $10 billion in excise taxes on shooting and archery equipment have been distributed to state wildlife agencies for wildlife conservation projects, hunter education courses, and public access improvements. In most states, Pittman-Robertson is the only source of funding for fish and game agencies.

But recent data paints a grim picture for the future of hunting and wildlife conservation.

Uncomfortable Numbers

The most recent U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service five-year study on fishing and hunting participation and spending shows troubling long-term trends that should give us all pause.

Between 2011 and 2016, the number of hunters declined by 16 percent—from 13.7 million to 11.5 million people. Additionally, the hunting population aged slightly, while the average number of days hunters spent afield decreased from 21 to 16. And, perhaps most distressing for hunters relying on healthy wildlife populations, spending on hunting equipment dropped 8.6 percent, from $14 billion to $12.8 billion.

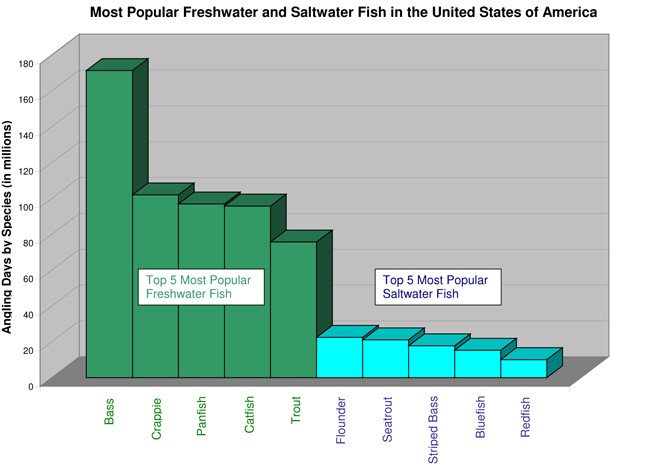

Fishing is the most popular outdoor recreation activity in 47 congressional districts, according to new data from the Outdoor Industry Association. Hunting doesn’t rank in the top three for a single district.

Clearly, maintenance of the status quo should be off the table.

Taking Aim at the Issue

Fortunately, our elected officials are making efforts to remedy this situation. On May 8, the House Natural Resources Committee unanimously approved a bill introduced by Rep. Austin Scott to modernize the Pittman-Robertson Act by allowing states to spend some of these funds on direct efforts to recruit, retain, and reactivate hunters. A companion bill from Sen. Jim Risch has strong bipartisan support and co-sponsorship.

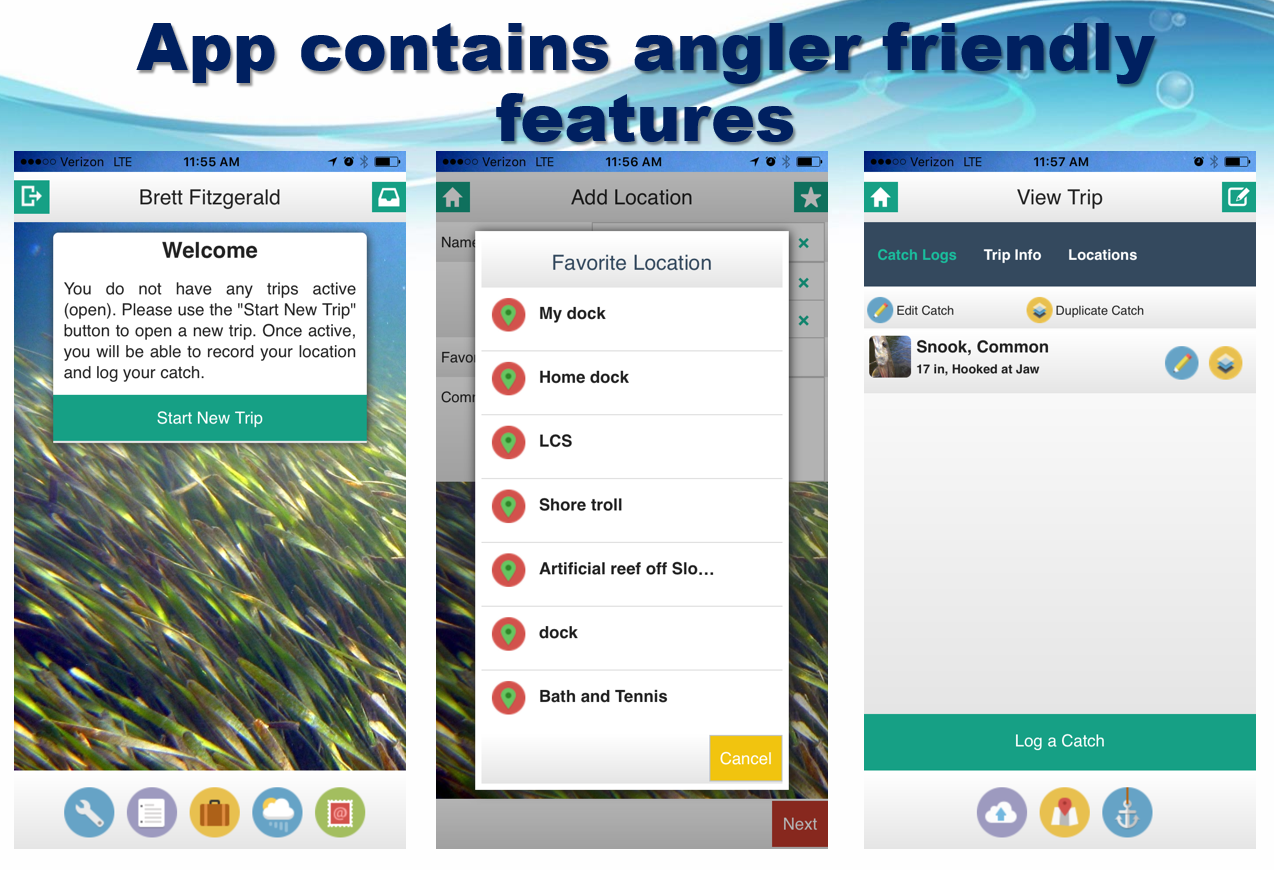

If passed into law, this could boost R3 efforts through mentoring and outreach via television or even social media—you know, where the younger generations spend their time.

“With this legislation, the current generation of sportsmen and women has a chance to leave a lasting legacy on the footprint of conservation—much like hunters did in 1937, when Pittman-Robertson was passed,” says Cyrus Baird, programs director for the Council to Advance Hunting and the Shooting Sports. “By allowing state fish and wildlife agencies more flexibility to use P-R funds to recruit, retain, and reactivate hunters, we are ensuring the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation will remain effective for generations to come.”

A Tackle Box for Information

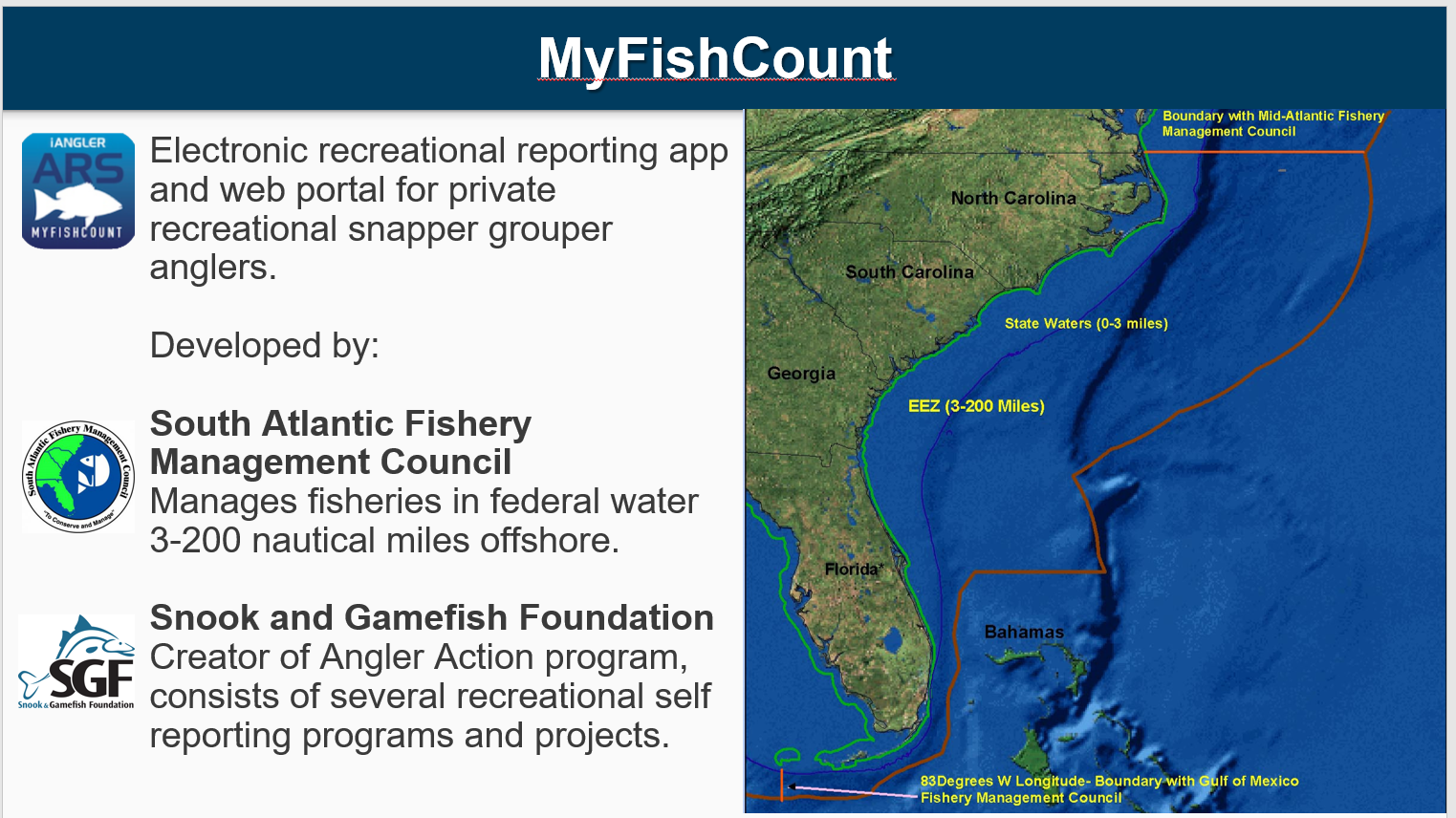

Champions of the “P-R Mod” effort are fairly sure that legislative changes will be worth it, because the model has already been successful on the fishing side. The Dingell-Johnson Act created the program that distributes excise taxes on boating and fishing equipment to the states for fish and habitat conservation, but with one key difference: Every year, about $12 million in Sport Fish Restoration funds go towards national angler R3 efforts.

This has led to programs like Take Me Fishing, the incredibly helpful initiative that provides resources for beginning anglers looking to purchase a license, tie a lure, identify a walleye, or read up on their state boating laws. Take Me Fishing has also partnered with state fish and wildlife agencies to reach out to Americans who are underserved and underrepresented in the fishing industry.

This is all made possible by Sport Fish Restoration funds and has been critical in growing fishing participation numbers and the economic impact of anglers across the country. Between 2011 and 2016, the angling population grew by 2.7 million people, while spending on fishing equipment increased by more than 36 percent.

The Bottom Line

As hunters, a portion of our purchases goes back to all wildlife—not just the species that hunters care about. And we have shown time and again that we are willing to pay even more to see fish and wildlife habitat thrive. But it won’t be enough unless we swell our ranks at the same time.

Given the foundational role hunters play in wildlife conservation, we should be bold in our pursuit of efforts to recruit, retain, and reengage America’s hunters for the next generation. Bringing Pittman-Robertson up to date is one pragmatic way to do that.

Top photo courtesy of Tim Donovan.

Second and third photos courtesy of Northwoods Collective.

More public land and better managed public land is a must.

If we are serious about solving this problem, there needs to be a way for other outdoor enthusiasts to provide funding via purchases of outdoor gear like camping equipment, tents, binoculars, etc.. Non-consumptive users dramatically outnumber hunters.

….and they’ve been freeloading for years. It’s aboht time they share in the burden of protecting and restoring wild places and the creatures that call them home.

I’ve tried to find a list of specific items (via google) that are taxed by the Pittman-Robertson Act without much luck. I always wonder when I see non hunters in the woods and wonder what they pay if any on their equipment?

From what I’ve read on https://wsfrprograms.fws.gov/ it ain’t much:

– 11% tax on firearms and ammunition

– 10% tax on pistols, handguns and revolvers

– 11% tax on bows, quivers, broadheads, points

– $0.43 per arrow shaft

The Dingell-Johnson model that includes the R3 efforts looks promising. However, I have a hard time believing paid “television or even social media” will recruit more hunters. It’s all about access, access, access. Why would we divert limited funds from research, surveys, management of wildlife and/or habitat, and acquisition or lease of land, just to line the pockets of facebook and the like? If this is a pilot program fine, but we need a sound calculation on cost-per-hunter-acquisition here.

– How much does it cost to recruit a hunter?

– How much does each new hunter in turn contribute per season vs estimated lifetime value to the Pittman-Robertson fund?

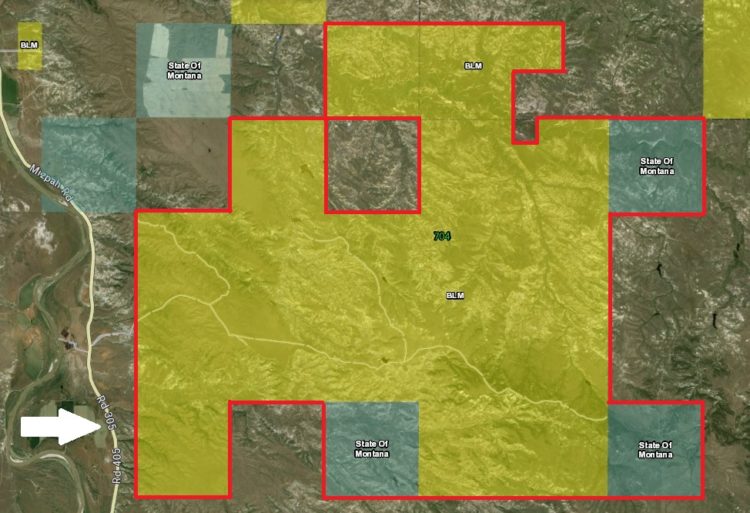

Being a public land hunter, I was surprised to read in the 2016 FHWAR that 85 percent of hunters hunted on privately-owned land (64 percent exclusively so). However, The largest single drop from in hunting expenditures from 2011 to 2016 is $6b in the ‘other’ category—a category that includes expenditures for lands owned and lands leased.

Comparing 2011 vs 2016 paints an interesting picture. Leased land actually grew in expenditures from $1.1b in 2011 to $1.4b in 2016, while the total acreage dropped from 420m to 131m. That’s a 289% increase in price-per-acre from $2.66 in 2011 to $10.34 in 2016.

Owned land expenditures dropped drastically from 6b to 1.6b. I guess once you buy land you’re less likely to buy it again in the future.

All this is to say, in the absence of good public land access for hunting and a Byzantine bureaucracy of clunky .gov websites, people are incentivized to hunt private. And private land hunters that can, or are willing, to buy or lease are getting squeezed.

Bureaucrats with remedial instruction programs and social media campaigns will not increase hunter recruitment

If you want more of anything, increase habitat and repress predation.

Works every time

By opening easily accessible public land we could create many new opportunities for hunter success, interest and mentorship.

Most states have thousands of acres in the Federal Refuge system

If hunting is allowed at all it’s extremely restricted.

Most refuges allow no trapping or predator hunting and much is closed to the public all together.

This could be changed with little or no expensive at all.

Simply ease restrictions and allow public hunting access on what is already public land.

Any any all efforts will be for naught as long as (for example) Clean Water Act protections are removed – especially those on wetlands and headwaters. What good is recruiting more anglers if habitats are degraded and bad water quality makes fish unsafe for consumption?

And I agree that excise taxes should be placed on items that nonconsumptive users of wildlife (birders, wildlife photographers, etc.) purchase; problem though is none of those things are “consumables” in the way that cartridges and arrows are. Unfortunately there’s no magic to be had.

And I, for one, have a really hard time imagining members of “Generation X-box” getting up well before dawn to be in a duck blind at the start of a hunt. Or streamside when the trout begin to rise. Or packing into the backcountry. Or… One of the REAL roadblocks to getting kids outside is those addictive screens they (and we) stare at all day. Oh, and the fact that they’re all terrified of pretty much anything that flies, crawls, swims or walks on 4 legs.

Of course the longterm issue was brought out a few years ago in a F&S (I think) article in which the author wrote that as the number of hunters declines, policy decisions on wildlife-related issues will be increasing made by non-hunters. Unlike some “Chicken Little” types who equate non- with anti-, the author was more sanguine; his point being that sportspersons who hunt/fish legally and ethically are the BEST illustrators of not only our shared heritage, but also of people who hold that heritage in the highest esteem. And it’s down to us to police ourselves and use programs like Operation Game Thief to weed out the bad apples.

As long as they keep taking away public land access the amount of hunters will keep dropping, not everyone can afford to hunt private land. You can do all you want to get youths involved in hunting but if there is not a place to hunt your waisting time. Youths depend on parents, and older people to take them hunting if there is no place to hunt they all stay home. Private land hunting might be where the money is, but public land is where the numbers are.