Anglers who report catch data using the latest apps help fisheries managers adjust seasons in real-time, so why are some still resistant to sharing?

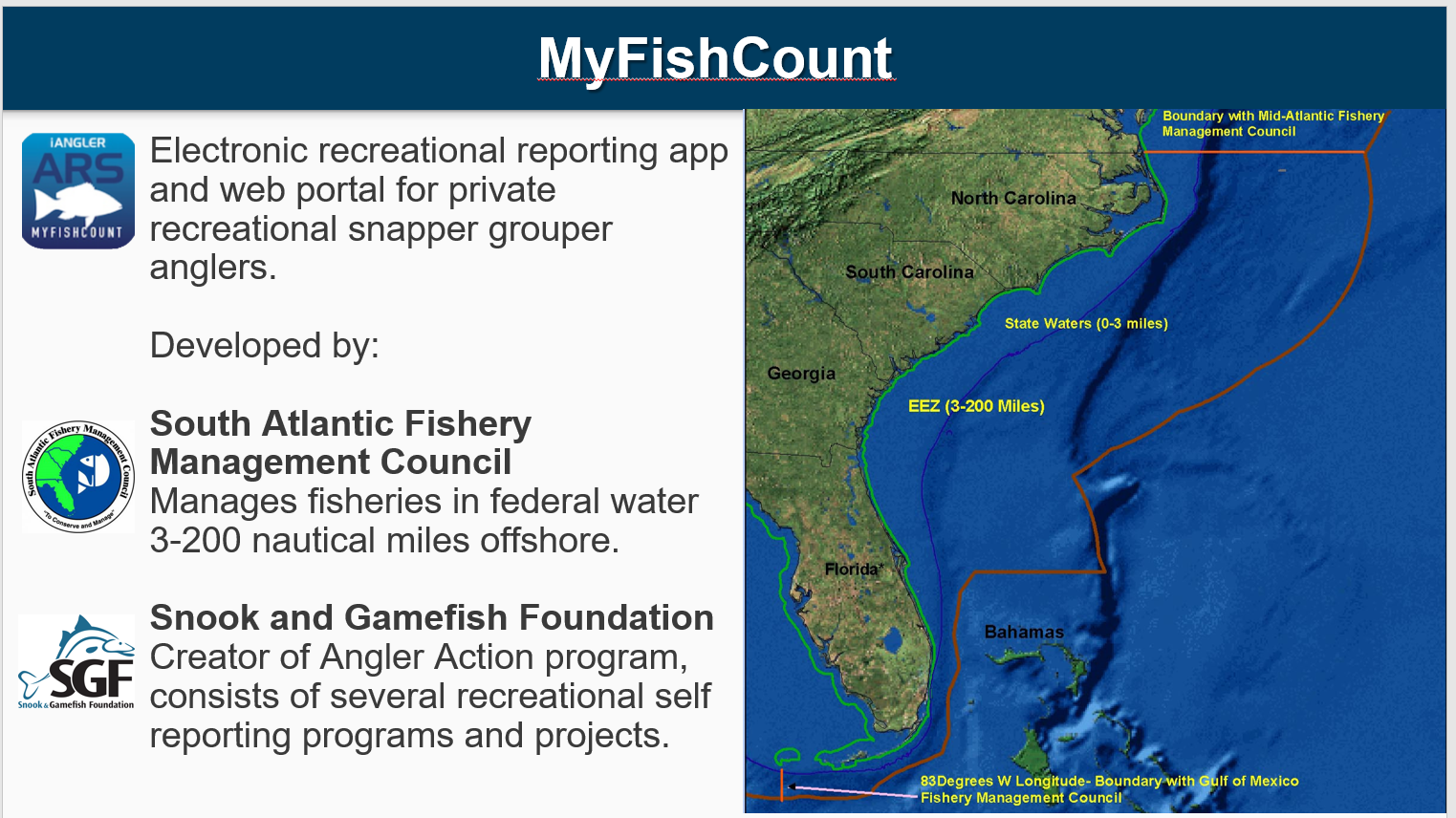

Recreational angler self-reported data has come a long way. As it has suddenly dominated many of the recreational fishery management discussions over the past year, one might think the concept has come out of nowhere. But the Snook and Gamefish Foundation (SGF) has been working on refining the process for almost a decade, and our work has provided some valuable results. The Angler Action Program (AKA iAngler), a service project of SGF, was born in 2010 after an historic cold event severely damaged a host of tropical Florida wildlife, including snook—a native and highly prized gamefish.

In response to the possible crisis, we partnered with Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to design and build a voluntary self-reporting database that would start to get a handle on just how hard the fishery was whacked by the extreme cold weather. Snook anglers—who range from passionate to completely obsessed—were an easy target for soliciting help.

There were many successes over the following years, most of them ‘firsts’ in the world of fishery management at the state level. After helping with the design of the database and angler survey, FWC left us to run and manage iAngler and its data. Participation was fairly high, with thousands of hours of snook-directed fishing trips reported within months of program initiation. FWC found data useful almost immediately in a few areas, particularly regarding data on the fish we let go, called ‘discards’ by researchers.

Within five years, iAngler was expanded to include all species of fish on a global range, and it was used directly in five different Florida stock assessments for snook, spotted seatrout, and red drum. This is the first time that data collected and managed by anglers was used in a state-level stock assessment.

Around that same time, a lab at the University of Florida began running some analysis of iAngler data and comparing it to numbers from the Marine Resources Information Program, which currently collects data for all federally managed fish species. Despite having some design flaws, especially where the program forces commercial models on recreational fisheries, MRIP is responsible for what has long been considered to be the “best available data” for use by federal agencies.

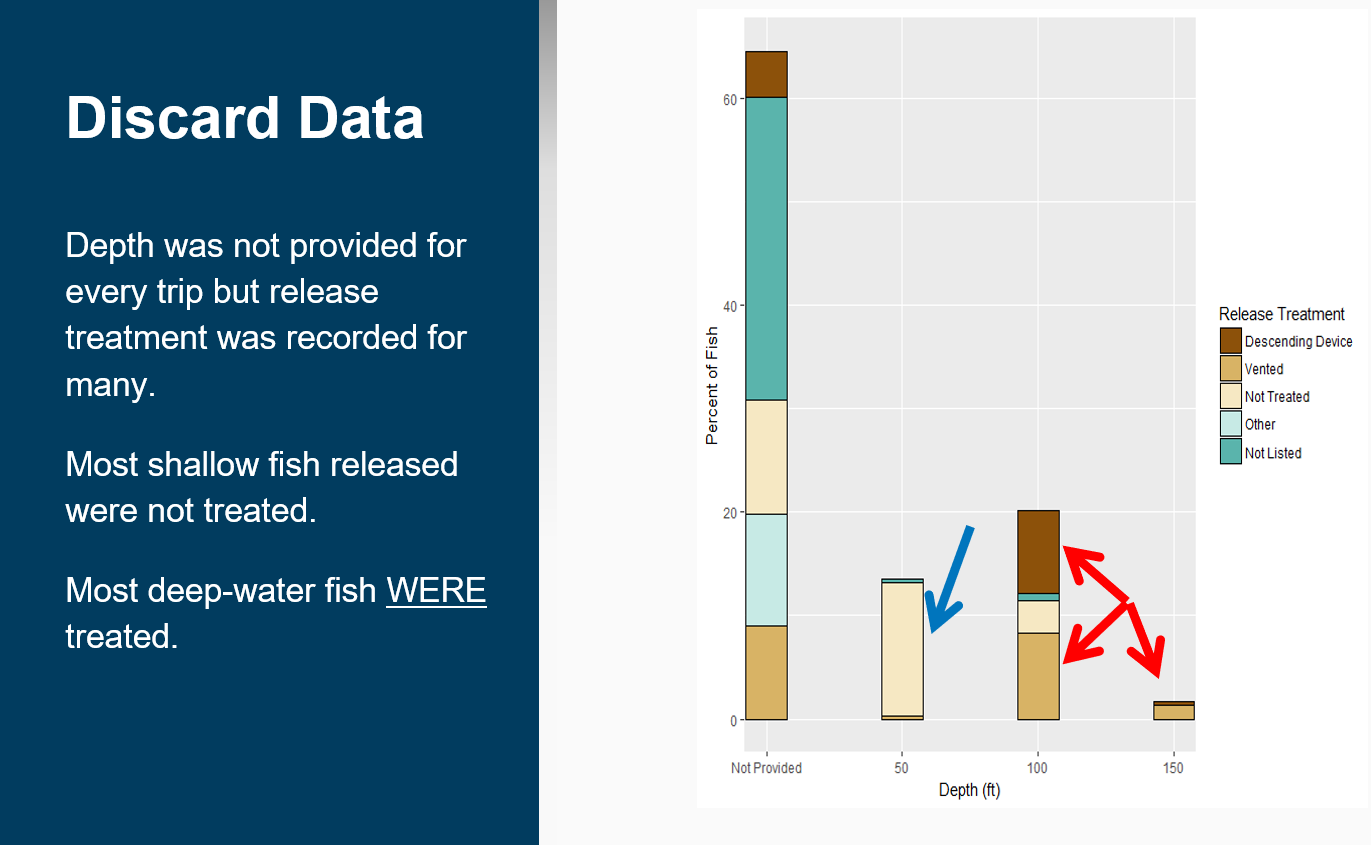

The UF studies focused on how many fish anglers are catching and how big the fish are. This is especially important with discards, as this is an area of fishery information where many species are ‘data poor,’ meaning whatever the best available data is, it ain’t enough.

In general terms, the UF study found that iAngler data in Florida did have some limitations, or biases, however for areas where enough anglers participated the data lined up nicely with MRIP.

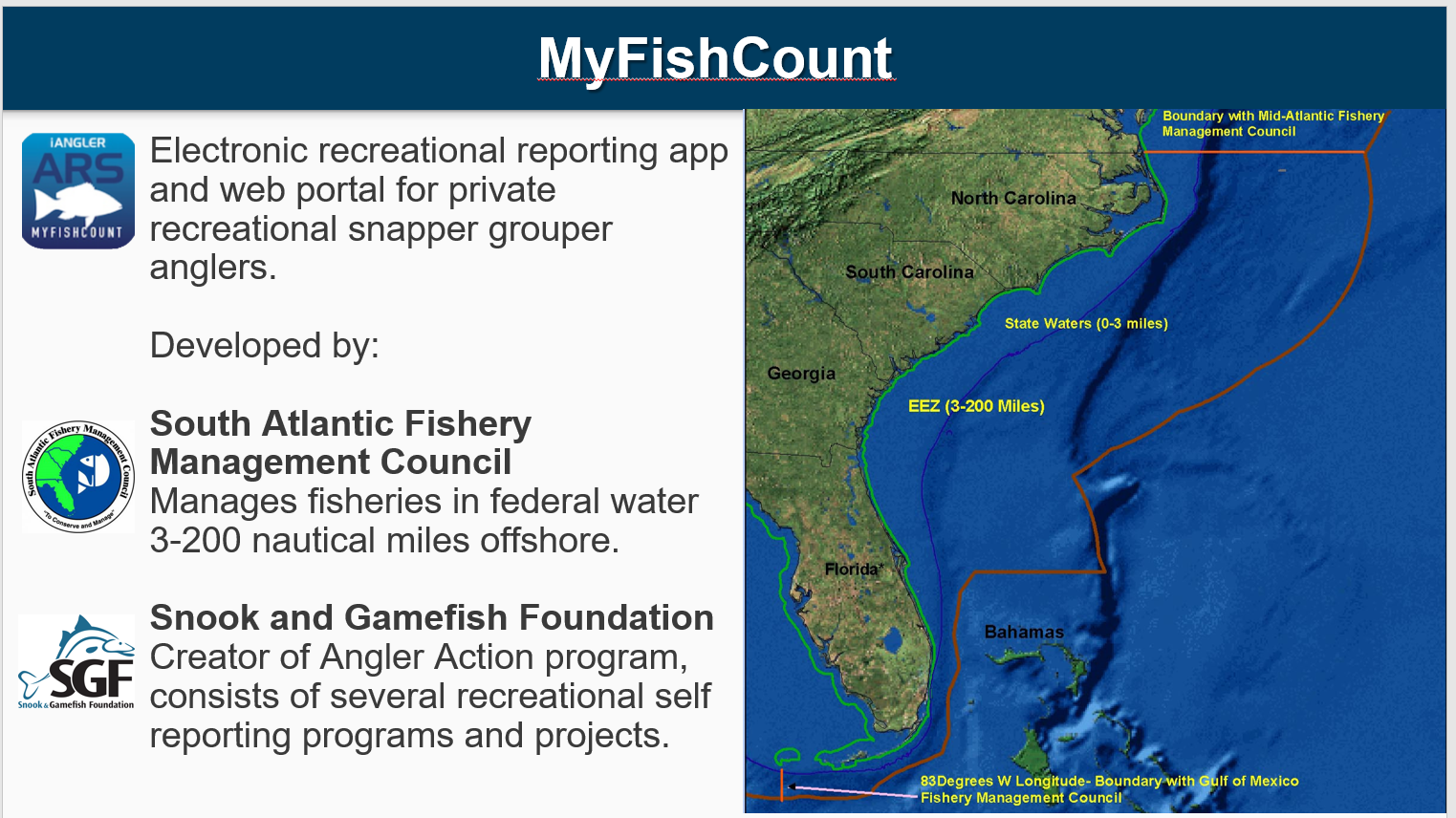

Right around the time these very positive results of iAngler data analyses started rolling in, the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC) reached out to SGF to see if we could partner up with the goal of getting a better handle on the Atlantic Red Snapper situation. Similar to the Gulf of Mexico, recreational anglers have been reporting anecdotally that they are experiencing an explosion in the population of this prized fish, yet the season had been closed since 2014 in the South Atlantic because the current data and modeling suggest that the population is still in trouble. Managers understood that there is a problem, but until data collection was improved or at least changed, their hands were mostly tied.

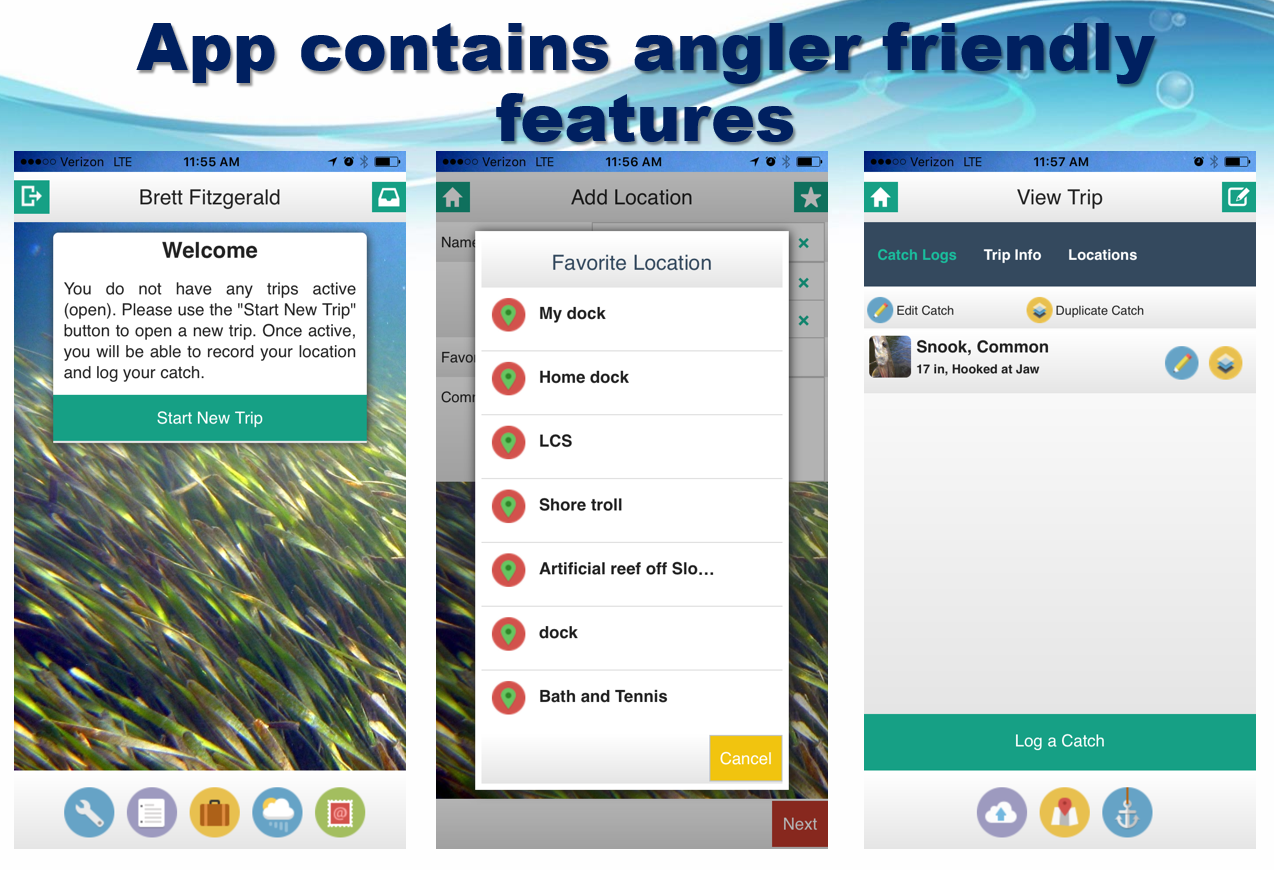

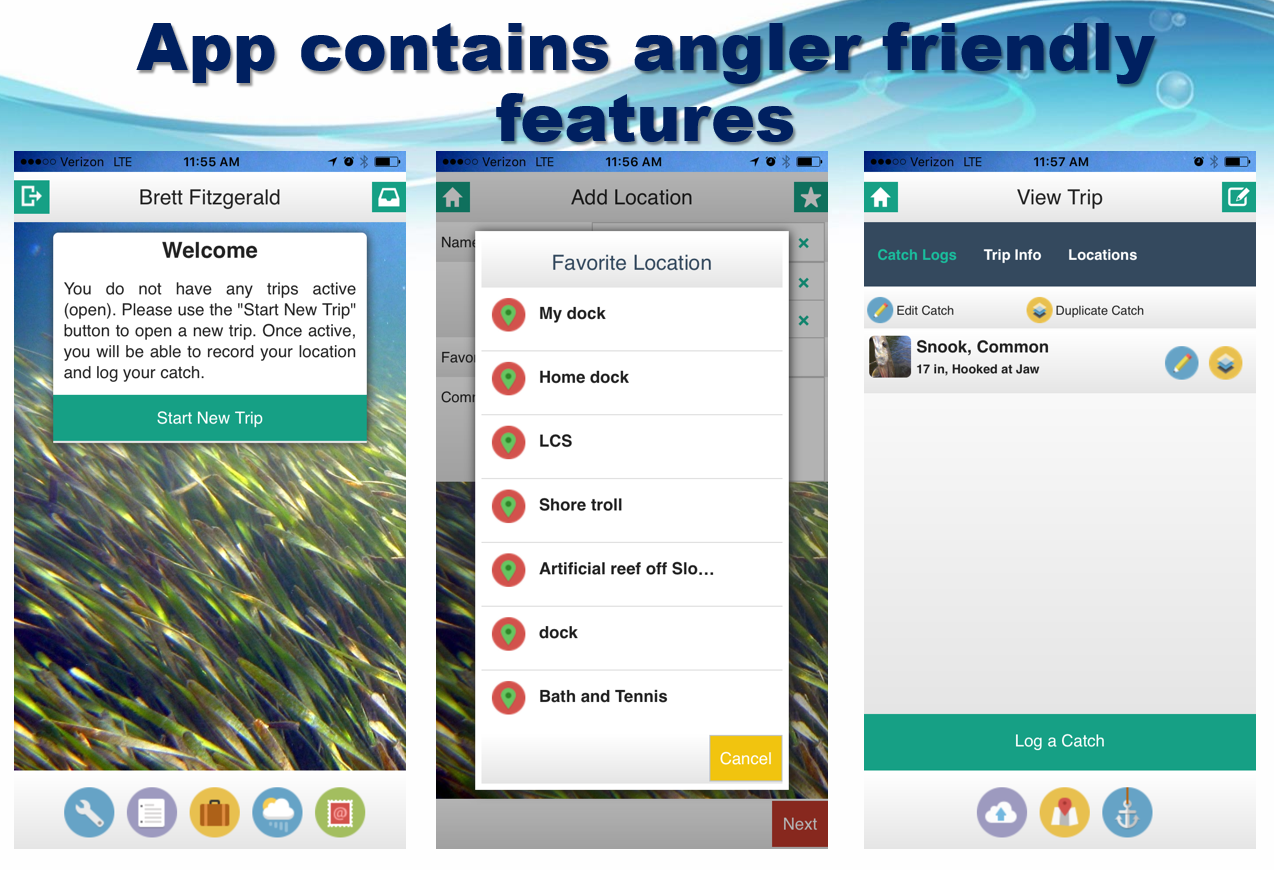

This new partnership led to a reporting tool called MyFishCount, which will allow anglers in the South Atlantic to report their catches – keepers and discards, along with a host of other data points – by this coming summer.

A pilot program was launched during the 2017 Atlantic Red Snapper season, and the results were again very positive. Anglers were able to report a variety of aspects of their planned snapper fishing trips through the system, researchers were able to see the data in real-time, and managers reacted to the data nearly as fast.

For example, the 2017 red snapper season was originally set for six days over two three-day weekends. Through MyFishCount, biologists and managers were able to see that the vast majority of planned fishing trips never took place, because the weather was not favorable for offshore fishing on those dates. Using this information, SAFMC was able to open a third long weekend of fishing.

The point is that anglers were asked to contribute, and because they did, their data was put to immediate good use. In this case, it led to more fishing access.

Not for nothing, the weather on that third weekend was pretty horrible, too. But this is ok for anglers: It means that the estimated harvest over the full nine-day fishing season is unlikely to overestimate the fishing effort, which could have led to less access in years to come.

“This is one of the few instances where you have technology, industry, fishermen, and scientists all agreeing on one thing—that we need better data in the recreational fishery—and most of us are seeing a similar approach to reaching that goal,” says Dr. Chip Collier, an SAFMC fisheries biologist who has been involved with the MyFishCount project since its inception.

He and his staff are very excited to have a new and improved version of MyFishCount up and running before summer 2018, and it will be functional for a wide variety of fish species, not just red snapper. “One of the great things about having it ready before the summer is that will be able to show anglers what self-reporting actually looks like,” says Collier. “The ‘fear of the unknown’ can make a lot of people hesitant to take the first step towards getting involved, and this will help.”

“The amount of positive comments we’ve received from anglers who participated has been great, and it feels like it really gives a voice to management,” says Kelsey Dick, SAFMC’s fishery outreach specialist. “I have been very grateful to see people coming together and being supportive of this project.”

The benefits of self-reporting are many. Through this kind of reporting, managers and biologists will get a better understanding of angler behavior on the water.

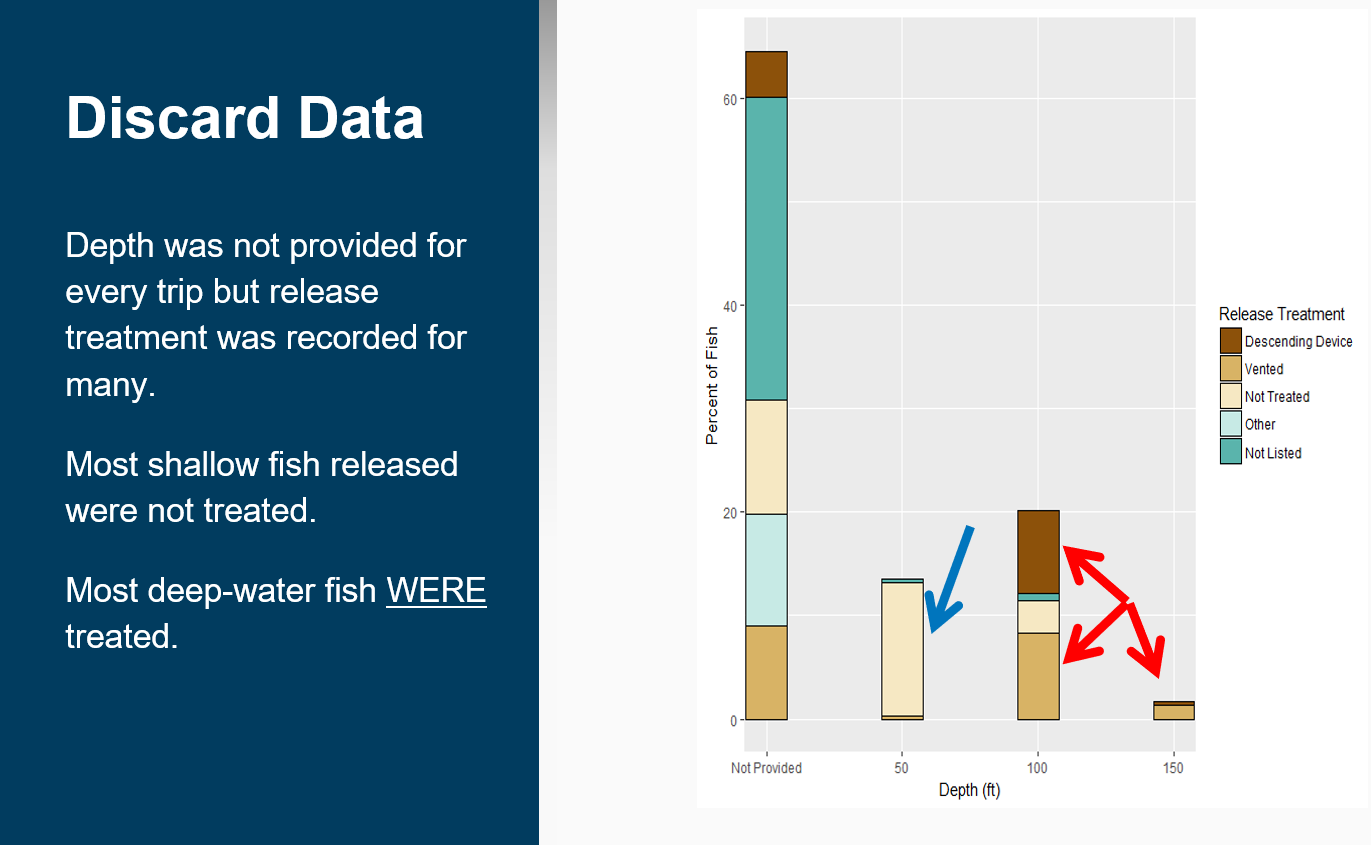

“We don’t have enough time to interview a lot of recreational anglers, so we don’t really know if people are using descending devices, or circle hooks, or other behaviors.” Dick said.

Mass, real-time self-reported data opens the doors to these types of data streams and that is extremely critical when trying to get a handle on how to best set management rules for a given species in a given region.

For example, in 2017 MyFishCount anglers reported very low use of descending devices or venting tools in shallow water (less than 5%), yet a very high (over 90%) in deeper water. Without the opportunity to self-report behavior like this, Councils have no way of estimating how many anglers are taking extra measures to help ensure fish survive release. And when you are managing ‘data poor’ species such as red snapper, any uncertainty in the modeling usually translates to less access.

Still, with all indicators pointing in a very positive direction, there is a lot of work to be done, and it is going to take time. “Managing expectations across the board is hard,” says Dr. Collier. Fishermen, scientists, managers and the industry all want this issue solved.

It is going to take some time, but the more anglers that get involved now, the faster we can improve the system and expand the functional uses. This type of data is not yet ready to answer questions like overall effort or fish abundance – researchers first need to understand just how this information represents the fishing community at large. But the mindset has changed greatly over the past couple years, from ‘the data is no good’ to ‘we must understand and measure biases in data, then account for those biases.’ This is an extremely encouraging trend.

The Snook and Gamefish Foundation is working with The American Sportfishing Association, Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and a host of other conservation and fishing industry groups, state and federal agencies to explore ways to better integrate self-reported data the use of technology to improve fisheries management.

Management is going to happen whether the data improves or not. So getting involved and reporting through iAngler now, no matter where you are, is a very important step for recreational anglers. It not only allows you to contribute immediately to a brighter fishing future, but also to keep tabs on how the technology is changing fishing behavior and management so you can help shape the direction in the future.

Brett Fitzgerald is the Executive Director of the Snook and Gamefish Foundation. He is also a contributing editor to Florida Sportsman Magazine, and a special education instructor in the Palm Beach County school system for where he promotes an academic curriculum through environmentalism and resource conservation. Fitzgerald is an avid guitar player, fly tyer, photographer and fisherman.