South Florida hunter and conservationist Richard Martinez, state chapter chair for Backcountry Hunters and Anglers and past guest of the MeatEater Podcast, explains why restoration work will improve habitat and access

When I was a young boy, our teenage babysitter taught my brothers and I about snipe. But the snipe she told tales of were elusive animals that could only be caught by hand – if you had a good enough eye to spot them and were quick enough to snatch them up. Her boyfriend took my brothers and I into a field of tall grass one sunny afternoon, and I’ll never forget watching him diving head-first for these mystical creatures, which the rest of us failed to spot, but always coming up empty-handed.

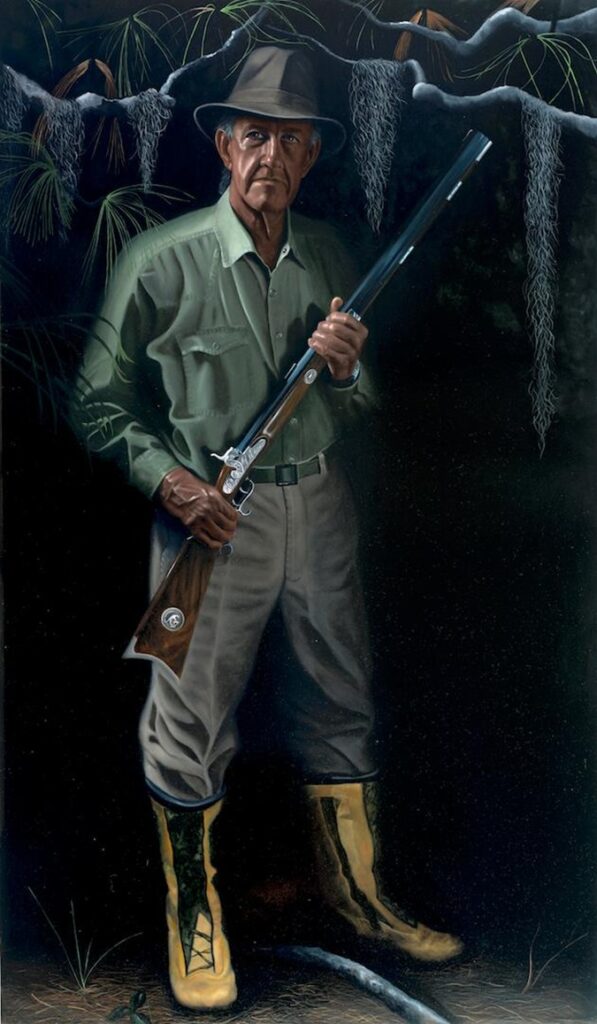

Only years later did I learn that snipe were real – small, tasty game birds found in functioning wetlands that still allow hunters to walk, flush, and hunt effectively – not the imaginary, four-legged, furry creatures I had conjured up as a kid. I never had a chance to participate in a real snipe hunt until recently, when I joined Richard Martinez, chapter chair for the Florida Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, as he hunted snipe in wetlands on public lands of the eastern Everglades – a region where he has stalked various species including whitetail deer, waterfowl, wild hogs, small game, and most of all, Osceola turkey, for the last decade.

“Turkey, definitely turkey, that’s my jam,” Martinez says. He knows Osceolas well enough that MeatEater’s Steve Rinella featured him in a successful hunt on an episode in 2023. Martinez’s knowledge comes from learning about Everglades habitat and hunting first-hand in the field over many years.

A Self-Made Florida Hunter

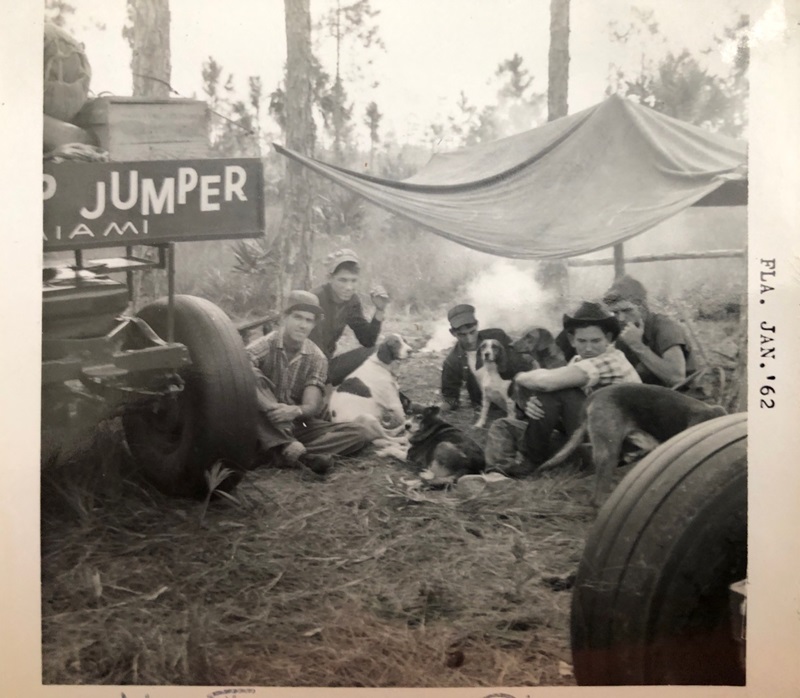

“I was exposed a little bit to hunting as a kid, but my father never hunted,” Martinez said. He explained to me that his uncles took him out in the woods a few times as a kid, which inspired curiosity in him, but he didn’t really get into hunting until he was an adult. And he did so in a very unique place – the uplands and wetlands on public lands of southeastern Florida.

I’ve known Martinez for a couple of years, since I first worked with him on a blog about hunting in the Everglades, and besides enjoying his company on a unique subtropical bird hunt, we had a chance to talk more about the importance of Everglades restoration from a hunter’s perspective. As we trod miles of wet prairie jumping Wilson’s snipe, he explained that the Everglades today offer a patchwork of both healthy habitat that’s great for hunting and fishing and areas that are highly degraded, compared to how they were historically. And after he’d bagged several birds, we chatted more at his truck about why he thinks current Everglades restoration projects are important, why he thinks hunters should support these efforts, and where he thinks more focus needs to be. Those wet prairies, working waters, and huntable landscapes don’t happen by accident – they are shaped by long-term restoration efforts like the ones TRCP members support.

How the Glades Have Changed

Martinez said that the Everglades today can be described as “sort of a Frankenstein’s monster.”

“It’s a resemblance of what it used to be. There are elements of it that feel intact, that feel pristine, and then there are other elements of it that you really feel the impact of man, whether it’s the invasives or the change in hydrology.”

He brought up a well-known but dire reality in conservation circles – that fully half of the historical Everglades are gone. That so much of the watershed has been lost. Yet the region still receives all of the water it used to, often with nowhere to move it.

“It’s turned into municipalities,” he said. “It’s my house, it’s my neighbor’s house, it’s where we live and work, as well as where the agricultural industry does business.”

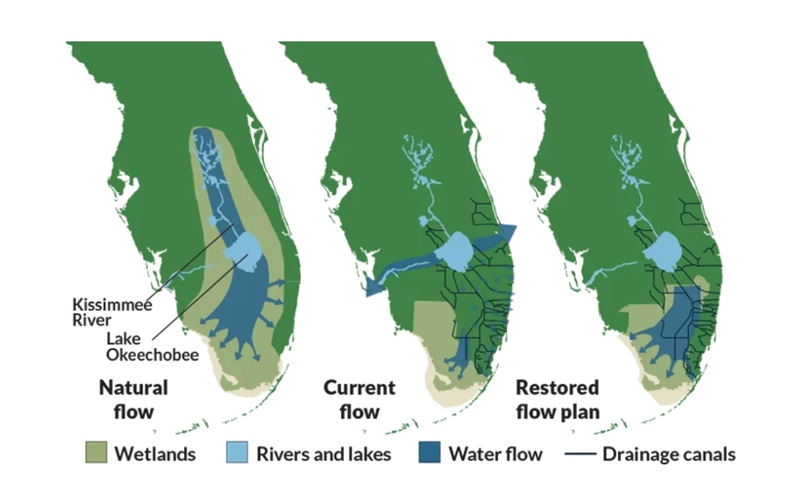

Decades ago, federal and state agencies worked with conservation groups and others develop a long-term, master plan for Everglades restoration known as CERP – the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan. CERP was first authorized by Congress through the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) of 2000, to provide a roadmap to be implemented by a federal-state partnership “to restore, protect, and preserve the region’s water resources by addressing the quantity, quality, timing, and distribution of water.” For hunters, these projects shape where water sits, when it moves, and what habitat looks like during the season

Still used today as the umbrella for most Everglades project work, CERP includes larger water storage and treatment projects like the under-construction Everglades Agricultural Area Reservoir and C-43 West Basin Storage Reservoir, a recently completed project west of Lake Okeechobee designed to hold 55 billion gallons in the 18-square-mile reservoir off the Caloosahatchee River to help store and manage basin runoff to meet estuary needs during the dry season and prevent harmful, high-volume discharges of fresh water during the wet season. The project will help regulate water flows, reduce toxic algae blooms off Florida’s coast, and protect marine fisheries. Collectively, all the CERP projects are designed to gradually undo as much damage as possible caused by a century of projects focused on draining and compartmentalizing the Everglades that led to their downward spiral. But they require ongoing federal and state funding to ultimately see completion.

Need for Projects Farther North

Also like Frankenstein’s monster, effective Everglades restoration must be made up of many collective parts. Martinez said he supports every project written into CERP, and he sees benefits for hunters and other South Florida residents from all current efforts. He also indicated that he would like to see more projects that address water flowing into Lake Okeechobee from the north and surrounding areas, to improve the water quality and the timing of the water going into the lake.

Lake Okeechobee, located near the northern reaches of the Everglades, once served as the largest source of fresh water for the Everglades, supporting the wetlands, food sources, and wildlife movements hunters have long depended on. Historically, it overflowed its southern bank in the wet season to create the vast, slow-moving “River of Grass” that flowed south all the way to Florida Bay, nourishing the entire ecosystem and diverse habitats along the way. But today the lake only partially serves that purpose, due to management necessary to protect lives and infrastructure.

“If we want our values and our interests to be heard, to be represented, we have to be involved.”

“I think a lot of the projects that do get the spotlight are the ones below the lake,” he said. “I think all those projects are really important and necessary, but I don’t think those projects are going to be as impactful until we figure out things further upstream.”

Martinez emphasized that hunters who care about the Everglades need to be highly engaged in conservation efforts to protect what they love. Not just by reaching out to decisionmakers by phone or action alert, but by showing up where management decisions are made. Like public meetings of the South Florida Water Management District and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. And he warns against hunters only making decisions based on social media posts, where “the loudest voice has the most impact.” After all, hunters are accustomed to science guiding management decisions through established seasons, population data, and regulations, rather than the volume of online debate.

“If we weren’t stakeholders at the table we would just be pushed out of the conversation,” he said. “If we want our values and our interests to be heard, to be represented, we have to be involved.”