This aquatic invasive species eats the striped bass, menhaden, and blue crabs so vital for the Bay’s health, recreational fishing, and economy

Great tasting: check. Will pull the rod from your hand: check. High chance of success: check.

It probably sounds like I’m talking about peak-season Gulf redfish or Long Island striped bass, but believe it or not, I’m talking about blue catfish – an incredibly resilient invasive species that is taking over the Chesapeake Bay’s waterways and harming important fisheries as it gobbles its way through them.

While native to middle America’s Mississippi and Ohio River watersheds, blue catfish are considered an aquatic invasive species in the Chesapeake Bay. Like other AIS threats around the country, their presence negatively impacts recreational fisheries, ecosystems, and economies. When TRCP and its partners convened an AIS commission two years ago, we had harmful species just like this in mind.

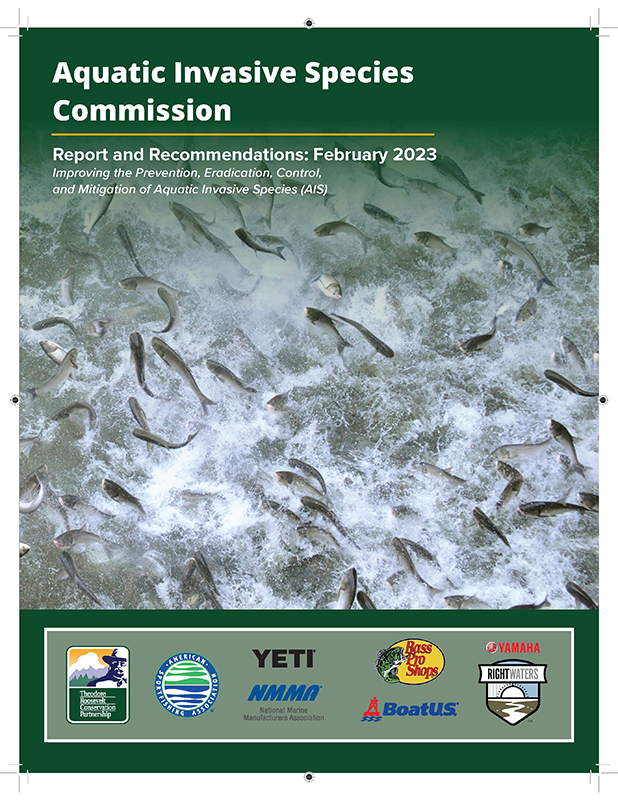

As the largest species of catfish in North America, blue cats can exceed 100 pounds thanks to a voracious appetite, unmatched adaptability, and a willingness to live just about anywhere and eat just about anything. So what are they doing in the Bay, and what can be done to blunt their impacts?

Unforeseen Consequences

In the mid-1970s, the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries were overfished and highly polluted. In response, fisheries managers in Virginia decided they needed to stock a different type of fish – a hearty specimen that could handle the poor conditions, offer anglers a good fight, and provide nice table fare. They settled on blue catfish. An added benefit they saw to this freshwater species was that it wouldn’t be able to spread beyond the targeted rivers.

“They thought because they are river fish they wouldn’t tolerate the saltwater conditions in the Bay,” said Dr. Noah Bressman, assistant professor in the Department of Biology at Salisbury University. “But they were wrong.”

Managers initially released blue catfish into the James and Rappahannock rivers, but they have since spread widely throughout most of the upper Bay. Today, blue catfish can be found in every major tidal river in Maryland, and in some locations make up as much as 70 percent of the total biomass.

“As an apex predator, invasive blue catfish continue to impact the ecological balance of the Chesapeake Bay by competing with native species for important forage species like menhaden and herring,” said Dave Sikorski, executive director of Coastal Conservation Association Maryland.

Not a Picky Eater

Dr. Bressman is a top expert on invasive blue catfish, researching such areas as their primary diet, feeding behavior, and ecology in the Bay. His lab uses boat-based electrofishing with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to catch hundreds of thousands of blue catfish for research. What they’ve learned is that these generalistic, opportunistic omnivores—much like coyotes or cockroaches—will eat anything.

Bressman’s research has turned up a 47-pound catfish with a whole adult wood duck in its stomach, and a 30-inch catfish with a 19-inch striped bass inside. Blue catfish eat many millions of blue crabs per year, and readily gorge on white perch, menhaden, striped bass (also known in Maryland as rockfish), even turtles and muskrats and their own young. On the Eastern Shore, they also target other important forage fish species – alewives and blueback herring. Tissue sampling evidence even suggests they are eating the eggs of striped bass, herring, and other fish, and as top predators they also compete with sportfish for the same prey.

“People think of catfish as slow-moving bottom feeders,” Bressman said. “But these are active predators. They eat anything and everything they can get their mouth around.”

If You Can’t Beat ‘Em, Eat ‘Em

Ask anyone, and they will tell you this problem is not going to go away. Bressman said that blue catfish are the most abundant fish, by biomass, in the rivers around the Bay. The problem has gotten so bad in the last couple decades that it’s actually generated a growing commercial fishery.

“What started as me targeting striped bass and hard crabs, and only fishing for blue catfish in between, has now gotten reversed,” said Rocky Rice, owner and operator of Piccowaxen Creek Seafood.

Rice has been commercially targeting blue catfish in the Potomac River for the last 12 years. He started fishing for these invasives merely to generate income in slow seasons, but now blue catfish are the main focus of his operation. Using primarily longlines and hoop pots, he targets fish in the best eating range of about 3 to 10 pounds.

And Rice is not alone. In 2022, commercial harvesters on the Potomac reported more than 3.1 million pounds of blue catfish landed, according to the Potomac River Fisheries Commission. This number far exceeds those for all other finfish species, except menhaden, harvested in the brackish river. By comparison, striped bass was the next highest fish species commercially landed at 428,000 pounds. And that’s just in the Potomac.

Unlike striped bass, whose numbers have been trending lower for years, blue catfish populations are practically impossible to eradicate, or even stunt. Rice says it’s one reason he targets this invasive.

“Granted I’m a fisherman and I need to make money,” Rice said. “But if I can minimize negative impacts on our native species also it’s a win-win.”

Dr. Bressman says just to keep the blue catfish population stable, fishermen must remove 15- to 30-million pounds of catfish from the Chesapeake Bay each year, and much more to reduce it. He asserts that without active human intervention, catfish could likely become the dominant predator in brackish portions of the Bay.

Fun to Catch

So the best solution to keeping blue catfish populations in check, and to help protect native species, is one that offers real rewards: Go fishing. Blue cats are known for growing big, fighting hard, and tasting far better than most people expect. They’re also fairly simple to coax a bite from, and in Maryland there’s no catch limit.

If you’ve got a rod and reel, and willingness to target a different sort of fish, Rice says you can fish virtually anywhere in the brackish and fresh portions of the upper Bay. Dr. Bressman can back this up. In a previous tournament targeting blue cats, he fished from shore to pass the time while he waited for boats to come back in for weigh-ins. He had to stop one hour into the eight-hour tournament, and still almost won the shore fishing category with a half-dozen fish.

CCA Maryland, along with partners like Yamaha Rightwaters, is working to raise awareness with recreational anglers to help get them into the game. To target the threat of aquatic invasive fish species in the state, they offer fishing tournaments and other events to help engage anglers. A good example is the Great Chesapeake Invasives Count, which launched April 1 and runs through March 31, 2025.

“To combat this looming issue, and empower anglers to do their part, CCA Maryland is proud to partner with Fish & Hunt Maryland, Maryland DNR, Maryland’s Best Seafood, and others to promote the opportunities for fishing that invasive catfish present, and support data collection efforts to help guide future management actions,” said Sikorski.

Even Better to Eat

“These aren’t your muddy-bottom catfish,” Bressman said. “They eat things we like to eat and that makes them taste better than other catfish.”

Bressman, Sikorski, and Rice all say they love dining on firm, flaky blue catfish filets, which taste quite similar to those of striped bass – largely because both species are active predators that compete for the same prey. The culinary value of this fish is catching on. Maryland’s Best, a state-run program that connects consumers with locally sourced agricultural products, offers a listing of 16 grocery stores and 24 restaurants that sell wild-caught Chesapeake blue catfish, to help support the state’s watermen and fight this invasive.

“It makes no sense for someone to buy a catfish that comes from overseas, because we have a better quality product right here,” Rice said. “We have to eat our way through this problem.”

Rice says he personally likes to deep fry the white, flaky filets, but has broiled and blackened them too. He’s even had blue catfish pot pie. He said their versatility and palatability is probably why chefs like these fish so much.

“I’ve fed it to a lot of my friends who’d said they didn’t like catfish,” he said, “and now that they’ve had it it’s one of their favorite foods.”

Do Your Part

If you do head out looking for blue catfish in the Bay area, be sure to share the photos and filets with family and friends – especially via online imagery – to help drum up interest. And whether or not you target these fish, if you ever catch one, be sure to not throw it back into the water alive (an exception being some parts of Virginia, where you need to be aware of a daily 20-fish creel limit and allowance for only one catfish over 32 inches).

If you don’t want to catch or cook blue catfish, you can always support Bay-area businesses that offer locally sourced blue catfish filets. The bottom line is that dealing with blue catfish is an all-hands-on-deck situation, so the conservation community needs a lot of people working to tackle it in different ways.

“We need a cultural shift,” Bressman says. “The more catfish you eat, the more striped bass and blue crabs will be in the Bay.”

Learn about TRCP’s AIS Report here.

The TRCP is your no-B.S. resource for all things conservation. In our weekly Roosevelt Report, you’ll receive the latest news on emerging habitat threats, legislation and proposals on the move, public land access solutions we’re spearheading, and opportunities for hunters and anglers to take action. Sign up now.