In a major conservation win, the state’s Wildlife and Fisheries Commission adopted a Notice of Intent late last week to create a minimum 1-mile coastwide buffer prohibiting commercial netting of Gulf menhaden and increasing fish spill penalties

Louisiana’s redfish – and anglers seeking them – may no longer be competing with the Gulf’s industrial menhaden fishery in nearshore areas, thanks to a Notice of Intent (NOI) adopted by the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission on October 5.

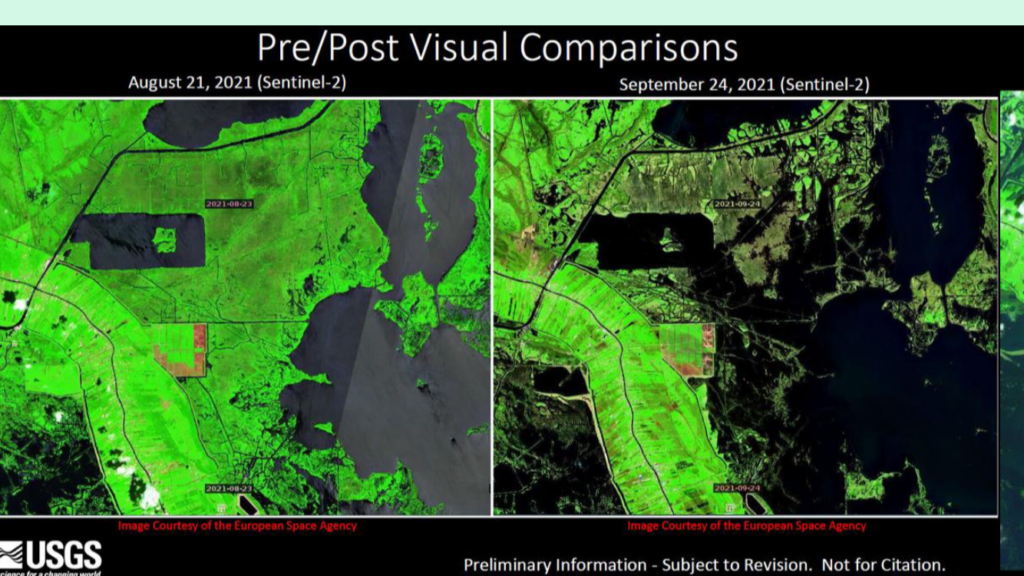

Acting in response to a series of net spills by two industrial pogie boat operators in September near Holly and Rutherford beaches, which resulted in an estimated 850,000 menhaden and hundreds of redfish killed, the commission issued an NOI establishing a minimum 1-mile coastwide buffer for the fishery in the state, with a 3-mile buffer required between Holly and Rutherford beaches. The buffer would widen an existing quarter-mile-wide area that is off limits to industrial pogie boats, which was established this season. The NOI also details more stringent penalties and reporting requirements for future net spills.

As part of the required process for regulatory change in Louisiana, the NOI will be open for further public comment and must still pass through state House and Senate Natural Resources Committee review before being finalized in early 2024.

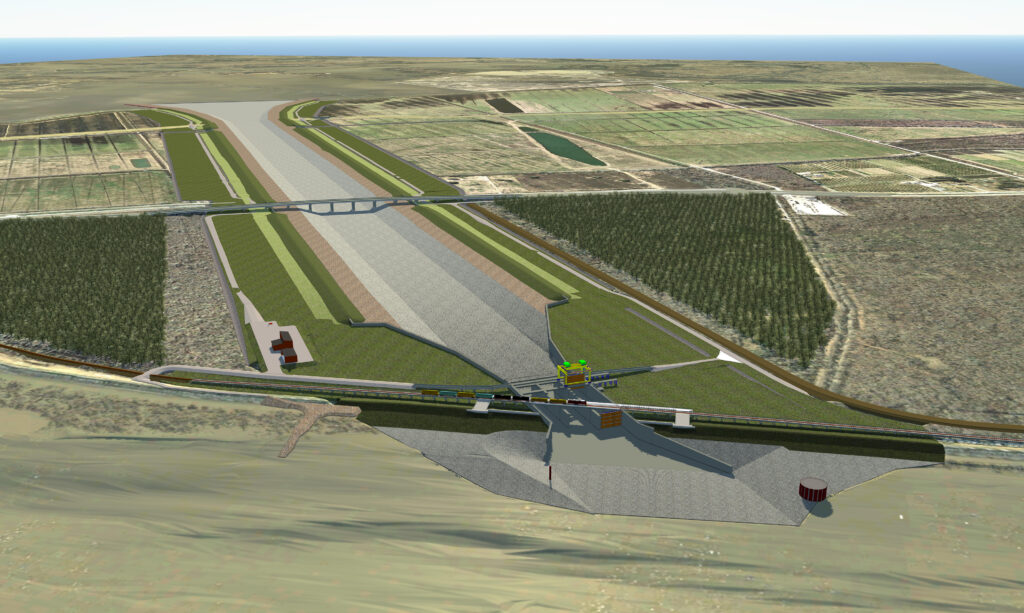

Gulf menhaden, also known as pogies, provide a critical food source for iconic Louisiana species like redfish and speckled trout. However, nearly 1 billion pounds of pogies are harvested by the industrial pogie fishery each year, mainly from Louisiana waters. To date, pogie boats have been allowed to fish shallows closer than 500 yards from Louisiana’s shorelines, stirring up sediment with their massive seine nets and impacting both fragile coastal habitats and iconic sportfish populations. Of most concern to anglers have been impacts to redfish, which spawn and congregate in these areas.

The recreational fishing community has been sounding the alarm about the industry’s impacts to sportfish populations and shorelines for years, all while accepting more and more limits on recreational fishing, including stricter size and creel limits on redfish and speckled trout.

“This represents a significant step forward in the conservation and management of Louisiana’s fisheries,” says Chris Macaluso, director of the Center for Marine Fisheries for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “The Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission thankfully has recognized that the concerns of anglers and conservation advocates are valid, and that Louisiana’s nearshore habitats need protection from foreign-owned, industrial pogie fishing boats. This is a big win for redfish, speckled trout, mackerel, dolphins, brown pelicans, and a host of other fish and wildlife, and a win for those who appreciate and enjoy Louisiana’s coast.”

“We thank the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission for taking this positive step towards protecting our fragile coastlines and the fish and wildlife that live there,” says David Cresson, executive director and CEO for the Coastal Conservation Association Louisiana. “The action of the commissioners last week, and many Louisiana legislators who encouraged that action, was a tremendous show of leadership. Now it is critical that we stay vigilant and focused as the NOI continues through the process and these much-needed regulations are finalized.”

Under the commission’s leadership, the Louisiana fishery could soon join the ranks of the other Gulf states who have expanded menhaden conservation regulations. While recreational fishing and conservation groups are still intent on establishing a scientifically based catch limit on menhaden in the Gulf of Mexico, they collectively recognize last week’s vote by the commission as a landmark positive step forward to protect redfish and the state’s coastal environment.

“The hundreds of small business owners that make up the Louisiana Charter Boat Association applaud the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries for recommending stronger menhaden regulations, and we commend the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission for affirming these recommendations. While more work remains to ensure that this Notice of Intent becomes law, today’s vote was a monumental step in the right direction,” says Richard Fischer, executive director for the Louisiana Charter Boat Association. “Years of teamwork from several organizations led to this moment, and today’s result would not have been possible without our dedicated and coordinated efforts. Thank you so much to every member of our coalition that played a role in making today’s vote happen.”

“Menhaden are a key prey species for many sportfish, including tarpon. Bonefish & Tarpon Trust appreciates the recent steps by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to expand protections for menhaden and to protect sensitive coastal habitats,” says Kellie Ralston, vice president for conservation and public policy for the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust. “We look forward to continuing to work with LDWF and our conservation partners to ensure long-term sustainability of the Louisiana menhaden fishery.”

“Louisiana’s anglers and recreational fishing businesses depend on healthy habitats and fish populations,” says Martha Guyas, Southeast fisheries policy director for the American Sportfishing Association. “ASA thanks the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission for taking this important step toward reducing impacts to coastal resources from the industrial menhaden fishery.”

“This is great news for menhaden, the recreational anglers of Louisiana, and the local businesses they support,” says Brett Fitzgerald, executive director for the Angler Action Foundation. “The door is now open to focus on and further necessary protections for our gamefish and their forage fish throughout the region. Many thanks to all who worked for so long on this important issue.”

Photo by Karlie Roland.