The state just broke ground on the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion—America’s largest and most expensive habitat restoration project to date—to breathe life back into a critical Gulf Shore basin and promote long-term fishery health.

The first time I launched a boat out of Empire, La., along the Mississippi River south of New Orleans, I had just graduated from high school in 1994.

I had spent a lot of time, to that point, fishing across Louisiana’s coast, from Delacroix, east of New Orleans, to Dularge in western Terrebonne Parish, but I never had the opportunity to traverse the speckled trout and redfish paradise of the eastern Barataria Basin with its seemingly endless maze of bayous, marsh ponds, lakes, and bays between our launching spot and the Gulf of Mexico.

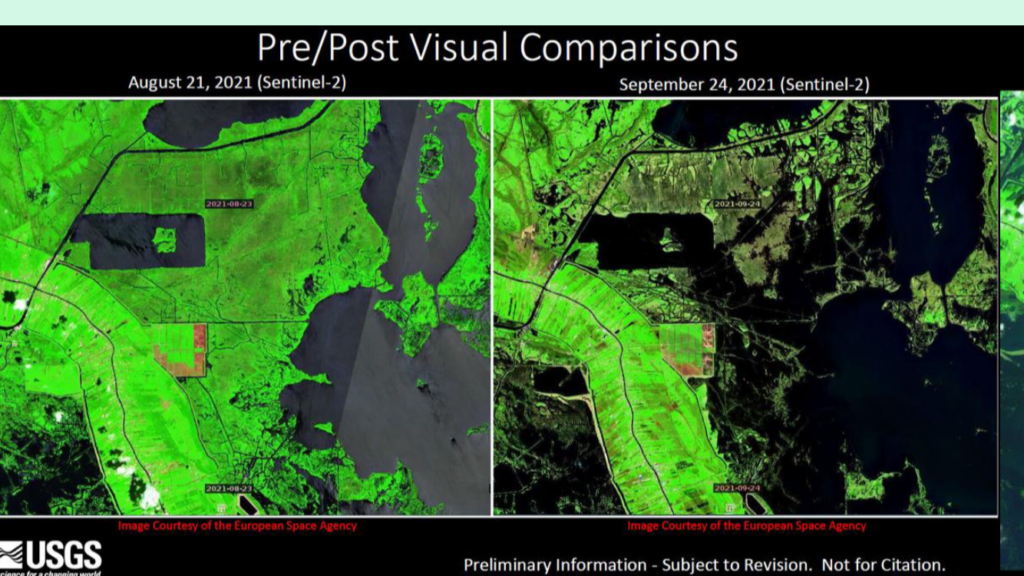

About a decade later, those bayous, lakes, and bays were either gone or almost totally unrecognizable, laid to waste by Hurricane Katrina’s unprecedented storm surge and land-eating ferocity. Other powerful hurricanes like Gustav, Ike, Laura, Delta, and especially 2021’s Ida, which washed away more than 100 square miles of coastal wetlands, have gouged and gashed the Barataria Basin in the 18 years since Katrina. These, along with nature’s consistent, relentless attacks and effects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, have further altered the basin.

What was once eight miles of marsh between Empire and the Gulf is now open water dotted with pilings and concrete riprap where old fishing camps and natural gas canals used to be. The Barataria Basin was 700 square miles of varying coastal marshes, swamps, bays, and islands from the west bank of the river to Bayou Lafourche in 1900. More than 430 square miles of that have vanished in the last century.

On August 10, the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, federal partners, and hundreds of Louisianans gathered just north of Empire to break ground on the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, a project designed to breathe life back into the Barataria Basin by reconnecting the Mississippi River to the marshes, bayous, islands, and ponds it originally built.

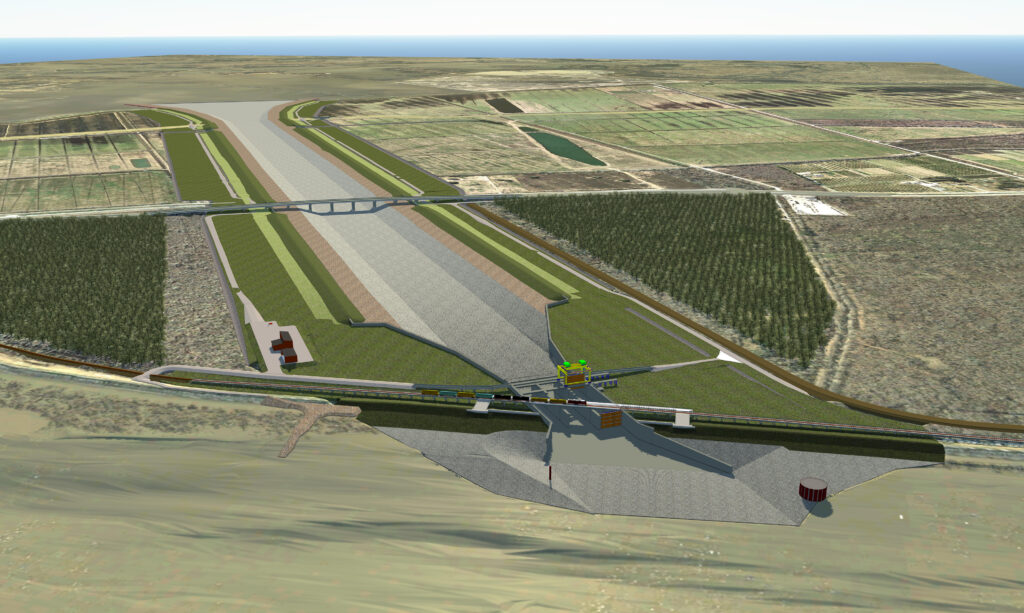

It is America’s largest, most ambitious, and most expensive habitat restoration project to date, designed to move as much as 75,000 cubic feet of sediment-laden water per second through a gate on the Mississippi River levee and a two-mile conveyance channel to mimic the connection that once existed between the river and its delta. The price tag is estimated at an astonishing $2.9 billion, almost all covered by penalties levied against BP and others for damages caused by the 2010 oil disaster including $660 million for construction from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund. Optimistically, the project is set for completion by 2028.

Thousands of years of annual floods and consistent connections between the river and the basin immediately to its west built what was once one of the world’s most productive fishery and waterfowl wintering grounds. But since that connection was cut off, beginning initially in the late 19th century to straight-line the river’s channel for ease of navigation and with levees built to control flooding, Barataria has been sinking and eroding faster than any other coastal basin in the world.

Wetland scientists, engineers, and fish and wildlife biologists have been predicting the basin’s eventual demise since the late 1800s because of efforts to disconnect the river from dozens of outlets south and west of New Orleans. Even back then, with a seemingly inexhaustible expanse of wetlands and barrier islands still present, there was an appreciation that removing the land-building sediment and the life-giving water and nutrients meant eventually the coastal habitat would vanish, taking away the fisheries and wildlife production and natural protection for coastal communities. However, the prediction was that the region and nation would both benefit so greatly from consistent navigation and flood control it would undoubtedly re-invest in the ecosystem at some point.

It took numerous devastating hurricanes, the worst oil spill in the country’s history, and the resulting fines, the Gulf lapping at the doorstep of New Orleans’ West Bank, more than 50 years of discussion, and the unweaving of bureaucracies and complex environmental laws and policies for that prediction to come true. While CPRA, federal agencies, and parish governments have invested billions in important marsh creation, ridge and barrier island restoration, and hurricane protection over the last four decades, none of those projects truly addressed the fundamental cause of the land loss like the Mid-Barataria diversion is designed to do.

While valuable, dredge-created barrier island and marsh restoration projects begin subsiding and eroding as soon as the project is finished. They are only built to withstand, at most, three decades of sinking, winds, and waves. Mid-Barataria, on the other hand, is designed for longevity as it will mimic the annual sediment slugs and wetland-sustaining water and nutrients that built the basin prior to straight-jacketing levees and jetties.

Certainly, reintroducing freshwater and sediment will change local fisheries. The Barataria Basin will become more like unlevied areas east of the river and to the west where the Atchafalaya River’s annual spring floods inundate coastal wetlands with water and sediment. While those changes have drawn harsh criticisms from commercial and even some recreational fishers, including the threat of lawsuits to try and stop the project, the narrative used by opponents that Mid-Barataria will mean the end of catching speckled trout, redfish, shrimp, crabs, and other species in the basin is simply not true. If the Barataria is to have any chance in the future of producing and sustaining the harvest of all those species, the Mississippi River must be re-connected, and the habitat rebuilt.

While the politics and the bureaucracy of diversions is complicated, the biological equation describing what’s happening in the basin is relatively easy to explain. The Mississippi River, when connected to the basin, regularly delivered sediment, water, and nutrients. That consistent engagement created a rich environment perfect for innumerable fish and animals to thrive in, but with seasonal changes based on how much freshwater was in the system. When the connection between river and marsh was cut off, the nutrients continued to leach out and feed the system as the wetlands degraded. Fisheries production exploded, but a timer had been set for eventual collapse of productivity while saltwater overtook and killed brackish and fresh marshland and swamp. At some point, there simply wouldn’t be enough marsh left to degrade.

Collapse is where we are now. Over the last 40-plus years of fishing the Barataria Basin, I can look back at too many days to count where friends and I caught trout and redfish until we didn’t want to cast any more. Literally hundreds of fish in a day. A two-person limit of 60 trout and redfish on ice by 8 a.m. wasn’t unusual. Fishing un-rivaled by anywhere in the country, the best place to catch a redfish in the world.

Until Katrina, unfortunately, we took for granted that it would always be like that. Louisiana’s current, ongoing, heated discussions over reducing trout and redfish creel limits because of productivity loss have their origins in devastating habitat loss. We just don’t have the fish we once did.

In the wake of Hurricane Ida, the Barataria Basin northeast of Grand Isle was unrecognizable. Miles and miles of marsh washed away. Communities 40 miles from the Gulf were covered in fetid mud from dying swamps, leaving residents to question how much of this loss and devastation could have been avoided if the projects to reconnect the river and sustain wetlands had been built 30 or 40 years ago instead of debated and dismissed as too costly. The longer these types of projects sit tangled in bureaucratic morass, the more habitat is lost as the costs skyrocket.

The Mid-Barataria Diversion gives Louisianans like me an opportunity to think positively about the future of our coast. Certainly, it will change the approaches we take to fishing the Barataria Basin. But it will give us a chance to experience a basin that is growing and an opportunity to see new land, gain new shorelines to cast to, and new ponds and grass beds to sustain a diverse fishery. For me, it’s a welcome change from the constant disappointment of knowing each year more and more of my home state will be lost to the Gulf of Mexico. It’s the best chance we have.

Groundbreaking photo at top courtesy of Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority

This is a great idea and is long overdue!