Why are some anglers writing off one of our best options for restoring these disappearing habitats?

Four League Bay might be the most remote destination on Louisiana’s coast. Even with a 300-horsepower outboard pushing a 24-foot bay boat, the ride from Terrebonne Parish’s Falgout Canal west to Four League takes nearly an hour of weaving through fresh and brackish marshes, bayous, lakes, and bays. Most of them are slalom courses of crab-trap floats. Alligators spring from the banks, and blue wing teal headed back to the Dakotas from their wintering grounds in Central and South America take flight.

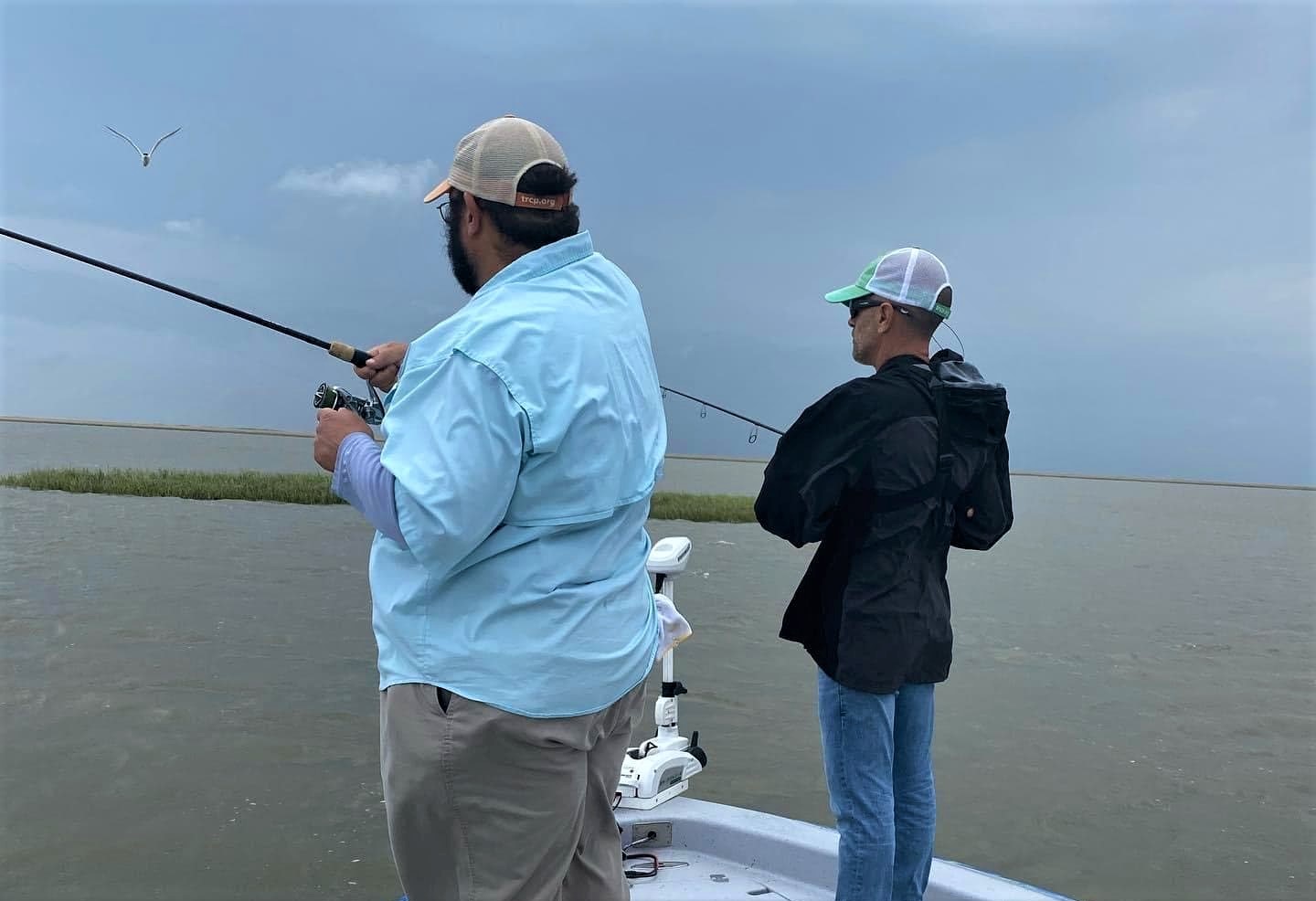

My good fishing buddy Todd Masson and I had been trying to get on the boat with Capt. Lloyd Landry for nearly two months, cancelling and rescheduling throughout the early spring as strong thunderstorms and unseasonably cold fronts pushed through Louisiana. Had we known that tropical storm and hurricane-force winds would sweep across the area just a couple hours after we returned to the marina, we might have cancelled again.

That day, the forecast gave us about a 5-hour window before thunderstorms were due to arrive. So, we put a stiff southeast wind at our backs and headed to some of the most unmolested, beautifully intact marsh in all of Louisiana to catch some hard-pulling, drag-screaming redfish.

Many Louisiana anglers write off Western Terrebonne Parish, especially the marshes and shorelines of Four League Bay, during the spring because the area is inundated with freshwater pouring from the Atchafalaya River. The assumption is that the 240,000 cubic feet per second of fresh, sediment-rich water that is building new marsh annually in the Atchafalaya Delta chases away the redfish and speckled trout.

The annual floods that scare away some coastal anglers are the exact reason the area teems with fish and the marshes are so healthy and intact. The nutrient-rich freshwater from the river mixes with the Gulf’s saltwater, creating a diverse forage of shrimp, crabs, pogies, crawfish, bluegill, mullet, and an assortment of other prey. The suspended sediment in the river water feeds the marsh, giving it a more stable soil structure for plants to root and submerged grass beds to grow.

It’s the perfect environment for fat, healthy redfish.

We picked a protected shoreline about seven miles from the river’s mouth. A handful of casts and Masson connected with a thick 20-inch redfish. A minute later, a bruising 29-inch red crushed a soft-plastic grub at the end of my line.

That pattern continued throughout the morning as Landry guided us into protected pockets and shorelines, picking away at healthy, well-fed redfish and black drum until the thunderstorms pushed us east to the marina just after noon.

Had the winds not limited our search area, we were set to chase speckled trout as well. Landry had been catching them in open lakes and bays as they transitioned from wintering grounds in interior marshes into their spring and summer feeding and spawning areas in the Gulf of Mexico.

We had options. Despite the strong winds that kept most anglers off the water that day, the benefit of healthy marshes laden with submerged freshwater grasses is that there are ponds and protected shorelines to duck into and hide—this works well for both fish and fishermen.

In far too many places along Louisiana’s coast, the options are running out. Marshes that have been cut off from annual, life-giving Mississippi River sediment by levees are more vulnerable to erosion from hurricanes or any other high-wind events. They are sinking below the water line, too, as seas gradually rise while the marsh subsides.

Nearly 2,000 square miles of wetlands, some of the most productive fish and wildlife habitat in the world, have been lost in the Mississippi River Delta, especially the basins between the mouth of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers, in the last century. To stem that loss and build back some marsh, the state of Louisiana is moving toward construction of sediment diversions both east and west of the Mississippi River below New Orleans. These structures will help to mimic the annual flooding that is sustaining and growing the marshes near the Atchafalaya River’s mouth—the processes that originally built all the marshes, swamps, and barrier islands of South Louisiana.

Some anglers and commercial fishermen are objecting strongly to the projects, claiming the freshwater will eliminate fishing. But there are few options for fixing this broken system other than using every single available sediment resource, especially the suspended sediment that comes with annual floods along the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers. Without reconnecting the Mississippi River to its delta, another 500 square miles of wetlands could be lost in the next century.

Anglers and fish have had to adjust to losing habitat far too frequently over the last 50 years in coastal Louisiana. Making adjustments as we regain habitat is something that I, and many other anglers, welcome.

Anglers need options. Without sediment diversions and all other efforts to rebuild and sustain our coast, we just might run out.