One of the country’s longest pronghorn migrations has a long road ahead

Archeologists recently uncovered what might be the oldest evidence of humans in North America near Oregon’s Hart Mountain. The artifacts, dating back to 14,000 B.C., help position the thousands of petroglyphs carved into the black basalt and rim-rock country from 6,500 years ago. These petroglyphs show how the Northern Paiute fished, hunted, and lived along the shore of Warner Lakes, at the base of Hart Mountain, and moved higher to hunt pronghorn and other big game during the summer.

Before European settlement, pronghorn roamed across western North America in the tens of millions, including on the high plains of what is now Nevada and Oregon. Unfortunately, unregulated hunting, disease, and habitat loss brought on by settlers caused a near collapse of the population. The area around Hart Mountain was one of the final strongholds for this unique species.

Determined to save the antelope, conservationists worked with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who in 1936, signed an executive order to establish two refuges (Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge and the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge) for the purpose of conserving pronghorn and other wildlife. Today, more than 800,000 acres on the Hart-Sheldon Refuge Complex are uniquely managed for wildlife conservation, providing essential habitat for bighorn sheep, pronghorn, mule deer, and others. The refuges have also provided high-quality, big-game hunting opportunities for decades.

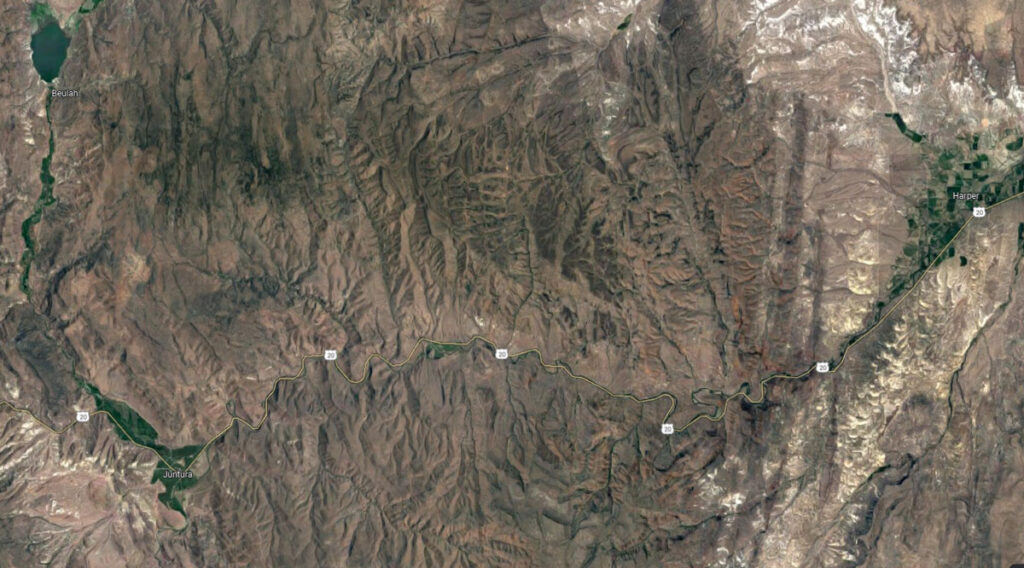

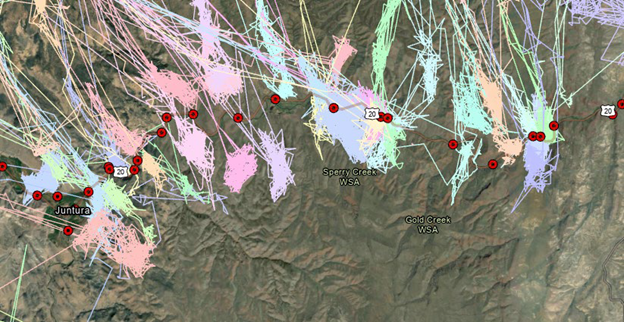

Since both refuges were established, researchers have learned a great deal about the wildlife and surrounding sagebrush steppe. Results from recent migration research have reinforced the importance of these two refuges as well as the adjoining 20 miles of BLM lands that separate them. From 2011-2013, biologists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service followed 32 female pronghorn in the Greater Hart-Sheldon. What they found was one of the longest pronghorn migrations in the country, spanning more than 100 miles across 3 million acres of public lands.

In general, pronghorn spend summers in the higher elevations at Hart Mountain, then move to lower-elevation winter range on the Sheldon. But the pronghorn herds also utilized the adjacent Bureau of Land Management lands as much or more than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service refuge lands throughout the year. Wildlife don’t recognize land ownership boundaries, and it’s critical that the habitat in this corridor remains unfragmented and ecologically intact for the long haul.

Unfortunately, over the past two decades, populations of mule deer, bighorn sheep, and sage grouse have declined, both on the refuges, and across the region. As wildlife biologists work to identify the cause of these concerning counts in hopes of reversing the trend, it’s clear that more financial resources, habitat restoration work, and management strategies are needed, both on BLM and USFWS managed lands.

That’s why the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership has asked the Department of the Interior to direct the USFWS and the BLM to work together with the local community to identify a cooperative management strategy and update their overarching management plans to best conserve and restore the habitat and big game populations, both on the refuges and the BLM lands between, so pronghorn can move freely across the high-quality habitats to promote healthy populations for future generations of hunters to enjoy.

Learn more about TRCP’s work in the Pacific Northwest here.

A version of this blog was originally published by the Bend Bulletin.

Photo credit: Kabsik Park