6893889291_04c685f966_o-Photo-by-Wyman-Meinzer-USFWS-1050-web

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

The prairie pothole region—which spans the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Iowa—is known for being the most productive waterfowl habitat in the world. The prairie potholes themselves are depressional wetlands that filter rain and snowmelt each year, some appearing on the landscape seasonally and others lasting all year. Together, the thousands of these wetlands serve as habitat for more than half of North America’s waterfowl. They are also central to the hydrology of the Northern Great Plains and provide some of our nation’s most high-value carbon sinks.

More than three decades ago, Congress saw the wisdom in conserving wetlands and ensured that landowners who converted or destroyed them wouldn’t be eligible for farm bill benefits. This policy, which has traditionally been referred to as “swampbuster,” was a good idea then and remains a good idea today. Hunters and anglers have supported this kind of accountability for decades, but to be truly effective and keep at-risk wetlands on the landscape, sound legislation isn’t enough.

We need credible agency implementation of compliance checks, as well. Ideally, compliance checks target wetlands at greatest risk to conversion and ensure that natural wetlands continue to serve their ecological function. But this may not be happening.

Last week, the Government Accountability Office released a study that revealed U.S. Department of Agriculture wetland specialists only reported a fraction of the wetland compliance violations that they encountered. Of the 417,000 tracts of land subject to swampbuster in the Dakotas, the GAO found that the Natural Resources Conservation Service had reported less than five violations between 2014 and 2018, indicative of a nearly non-existent enforcement regime.

NRCS wetland specialists explained that they do not report potential violations unless it is on a tract of land being inspected. Any wetland drainage visible across property lines, in view of the road, or on aerial imagery is not reported because doing so would undermine the relationships between landowners and the NRCS field staff providing technical assistance.

In short: The NRCS doesn’t want to be the bad guy, and wetlands get drained as a result.

Other farmers don’t want to the bad guys, either. The GAO study revealed that Farm Service Agency-run county committees, which are made up of neighboring landowners tasked with assessing good faith attempts at compliance, approved appeals on violations at wildly differing rates across county and state lines and often without clear justification.

This isn’t the first time there has been an issue with USDA’s enforcement of wetland compliance. In 2017, the agencies responsible were referring to outdated maps rather than going on real-time site visits to confirm wetlands were not being drained.

And this week’s report unveiled other complications. NRCS offices in all four Prairie Pothole Region states failed to follow the agency’s guidance to conduct annual quality control reviews from 2017 to 2019. The officials from NRCS headquarters in Washington, D.C., who are directed to oversee these reviews, were not involved.

Finally, despite the agency’s own guidance handbook, the NRCS selected properties for compliance checks—just one percent of the total lands subject to enforcement—based on random selection and not based on which lands are at highest risk of conversion. According to the GAO, between 2014 and 2018, the NRCS carried out compliance checks on 5,683 tracts in the four PPR states, that’s just over 0.5% of those subject to wetland compliance.

With its report, the GAO included a set of recommendations for the agency to improve their effectiveness in the field, available here. But sportsmen and sportswomen should demand that anyone compromising wetlands habitat, especially when it supports so many of our hunting and fishing opportunities within the PPR region and beyond, should not be able to benefit from the farm bill.

High commodity prices in the early 2010s resulted in record numbers of wetland determination appeals, as landowners sought to put more acreage into production. As agricultural markets recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, the pressure on prairie potholes and wetlands is only going to increase. We cannot afford for the USDA to turn a blind eye as bad actors take advantage of farm programs and the American taxpayer. The TRCP and its partner organizations will continue to work with Congress and USDA leadership to develop and bring to bear the policy and culture changes necessary to stem this tide of habitat loss.

Image courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Legislation invests in digitized, integrated mapping resources for outdoor recreation

The Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership celebrated the reintroduction of a House bill that will enhance outdoor recreation on public lands by investing in modern technology that allows sportsmen and sportswomen to know exactly which lands and waters they can access.

U.S. Representatives Blake Moore (R-Utah), Kim Schrier (D-WA), Russ Fulcher (R-Idaho), and Joe Neguse (D-CO) introduced the bipartisan Modernizing Access to Our Public Land (MAPLand) Act to the House of Representatives on Tuesday.

The MAPLand Act would digitize recreational access information and make those resources available to the public. The legislation would also provide federal land management agencies with funding and guidance to create comprehensive databases of available map-based agency records related to recreational access and use.

“Access is one of the most important issues facing hunters and anglers today, and the MAPLand Act is a commonsense investment to ensure all Americans can take full advantage of the recreational opportunities on our public lands,” said Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “In addition to making it easier for public land users to stay safe and follow the rules while in the field or on the water, this bill would allow our agencies to manage and plan more effectively while also reducing the potential for access-related conflicts between recreators and private landowners. Simply put, this legislation promises to help more people get outdoors. We appreciate these representatives’ leadership to introduce this bill in the House and our community is eager to help move the MAPLand Act through Congress.”

The bill includes language to digitize information about:

• legal easements and rights-of-way across private land;

• year-round or seasonal closures of roads and trails, as well as restrictions on vehicle-type;

• boundaries of areas where special rules or prohibitions apply to hunting and shooting;

• and areas of public waters that are closed to watercraft or have horsepower restrictions.

Currently, many of the easement records that identify legal means of access into lands managed by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management are stored at the local or regional level in paper files. This makes it difficult for hunters, anglers, and even the agencies themselves to identify public access opportunities. For example, of the 37,000 existing easements held by the U.S. Forest Service, the agency estimated in 2020 that only 5,000 had been converted into digital files.

In addition to improving the public’s ability to access public lands, the bill would help land management agencies — in cooperation with private landowners — prioritize projects to acquire new public land access or improve existing access. According to a report by the TRCP and onX, a digital-mapping company, more than 9.52 million acres of federally managed public lands in the West lack permanent legal public access because they are surrounded entirely by private lands. Digitizing easement records would be the first step towards addressing this challenge systematically.

Last year, more than 150 hunting- and fishing- related businesses signed a joint letter calling on congressional leadership to pass the MAPLand Act. From gear manufacturers and media companies to guides, outfitters, and retailers, the letter signers emphasized the importance of outdoor recreation opportunities on public lands to their bottom lines.

In addition, conservation groups across the country applauded the leadership shown by lawmakers to invest in the future of America’s public lands system.

The bill was also introduced in the Senate in March by U.S. Senators Jim Risch (R-Idaho) and Angus King (I-Maine) alongside Senators Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), Susan Collins (R-Maine), John Barrasso (R-WY), Joe Manchin (D-WV), Martin Heinrich (D-NM), Steve Daines (R-Mont), and Mark Kelly (D-Ariz).

Photo: Maven/Craig Okraska

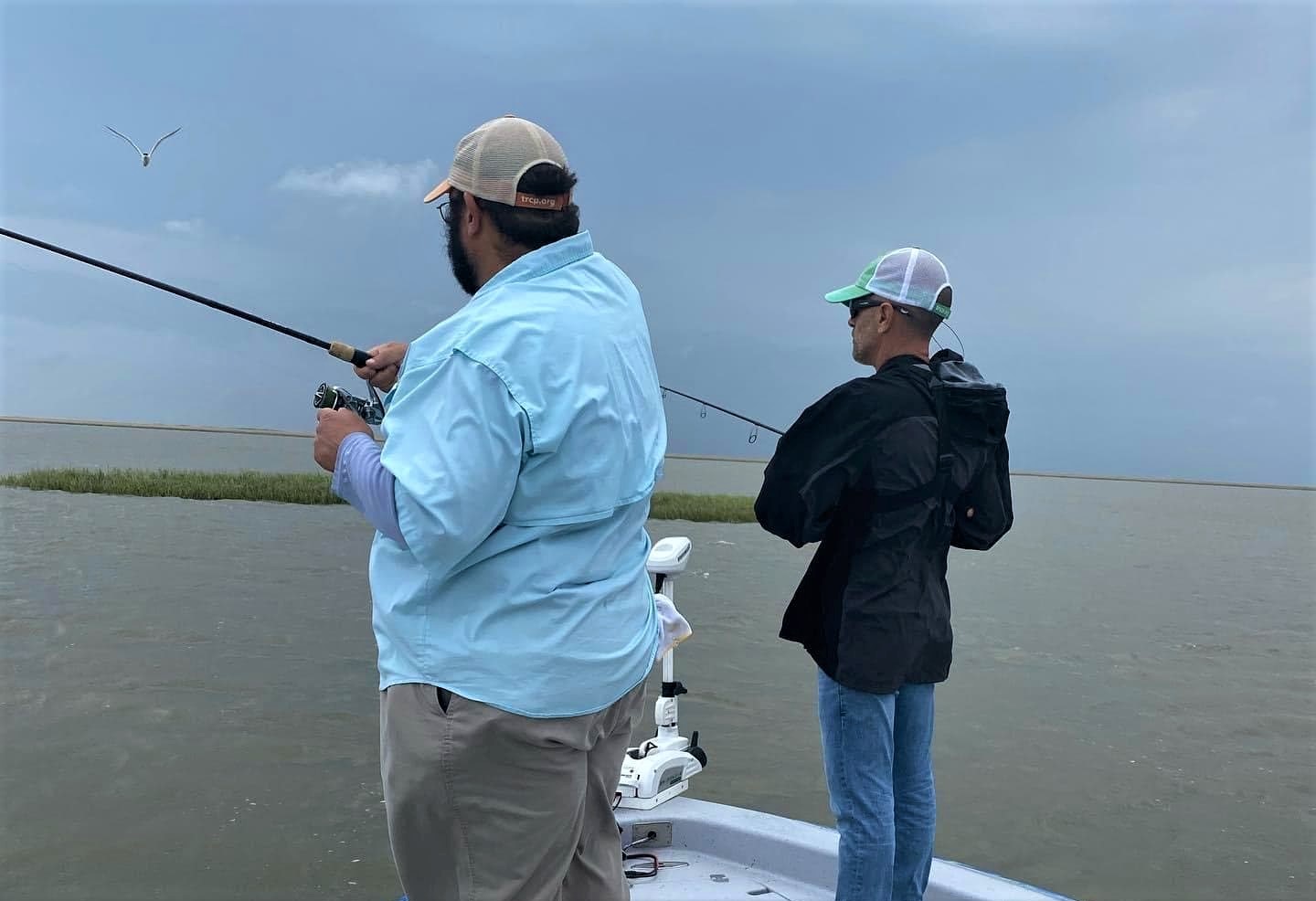

Four League Bay might be the most remote destination on Louisiana’s coast. Even with a 300-horsepower outboard pushing a 24-foot bay boat, the ride from Terrebonne Parish’s Falgout Canal west to Four League takes nearly an hour of weaving through fresh and brackish marshes, bayous, lakes, and bays. Most of them are slalom courses of crab-trap floats. Alligators spring from the banks, and blue wing teal headed back to the Dakotas from their wintering grounds in Central and South America take flight.

My good fishing buddy Todd Masson and I had been trying to get on the boat with Capt. Lloyd Landry for nearly two months, cancelling and rescheduling throughout the early spring as strong thunderstorms and unseasonably cold fronts pushed through Louisiana. Had we known that tropical storm and hurricane-force winds would sweep across the area just a couple hours after we returned to the marina, we might have cancelled again.

That day, the forecast gave us about a 5-hour window before thunderstorms were due to arrive. So, we put a stiff southeast wind at our backs and headed to some of the most unmolested, beautifully intact marsh in all of Louisiana to catch some hard-pulling, drag-screaming redfish.

Many Louisiana anglers write off Western Terrebonne Parish, especially the marshes and shorelines of Four League Bay, during the spring because the area is inundated with freshwater pouring from the Atchafalaya River. The assumption is that the 240,000 cubic feet per second of fresh, sediment-rich water that is building new marsh annually in the Atchafalaya Delta chases away the redfish and speckled trout.

The annual floods that scare away some coastal anglers are the exact reason the area teems with fish and the marshes are so healthy and intact. The nutrient-rich freshwater from the river mixes with the Gulf’s saltwater, creating a diverse forage of shrimp, crabs, pogies, crawfish, bluegill, mullet, and an assortment of other prey. The suspended sediment in the river water feeds the marsh, giving it a more stable soil structure for plants to root and submerged grass beds to grow.

It’s the perfect environment for fat, healthy redfish.

We picked a protected shoreline about seven miles from the river’s mouth. A handful of casts and Masson connected with a thick 20-inch redfish. A minute later, a bruising 29-inch red crushed a soft-plastic grub at the end of my line.

That pattern continued throughout the morning as Landry guided us into protected pockets and shorelines, picking away at healthy, well-fed redfish and black drum until the thunderstorms pushed us east to the marina just after noon.

Had the winds not limited our search area, we were set to chase speckled trout as well. Landry had been catching them in open lakes and bays as they transitioned from wintering grounds in interior marshes into their spring and summer feeding and spawning areas in the Gulf of Mexico.

We had options. Despite the strong winds that kept most anglers off the water that day, the benefit of healthy marshes laden with submerged freshwater grasses is that there are ponds and protected shorelines to duck into and hide—this works well for both fish and fishermen.

In far too many places along Louisiana’s coast, the options are running out. Marshes that have been cut off from annual, life-giving Mississippi River sediment by levees are more vulnerable to erosion from hurricanes or any other high-wind events. They are sinking below the water line, too, as seas gradually rise while the marsh subsides.

Nearly 2,000 square miles of wetlands, some of the most productive fish and wildlife habitat in the world, have been lost in the Mississippi River Delta, especially the basins between the mouth of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers, in the last century. To stem that loss and build back some marsh, the state of Louisiana is moving toward construction of sediment diversions both east and west of the Mississippi River below New Orleans. These structures will help to mimic the annual flooding that is sustaining and growing the marshes near the Atchafalaya River’s mouth—the processes that originally built all the marshes, swamps, and barrier islands of South Louisiana.

Some anglers and commercial fishermen are objecting strongly to the projects, claiming the freshwater will eliminate fishing. But there are few options for fixing this broken system other than using every single available sediment resource, especially the suspended sediment that comes with annual floods along the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers. Without reconnecting the Mississippi River to its delta, another 500 square miles of wetlands could be lost in the next century.

Anglers and fish have had to adjust to losing habitat far too frequently over the last 50 years in coastal Louisiana. Making adjustments as we regain habitat is something that I, and many other anglers, welcome.

Anglers need options. Without sediment diversions and all other efforts to rebuild and sustain our coast, we just might run out.

The Biden Administration announced a plan to conserve, connect, and restore 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030. The “America the Beautiful” initiative is a ten-year conservation and restoration plan that focuses on public, private, and tribal lands and waters.

“We appreciate the administration’s focus on fostering collaborative solutions to conserve our lands and waters, while including feedback from sportsmen and sportswomen,” said Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “Whether it be climate change or public access or habitat loss, the issues facing our outdoor places are multi-faceted and require thoughtful leadership. As this plan continues to take shape, the details will matter, and the hunting and fishing community is ready to bring solutions to the table.”

The plan is a combined effort between the Departments of Interior, Agriculture, and Commerce and the Council for Environmental Quality. Early recommendations include many of TRCP’s priorities, including:

“The ambition of this goal reflects the urgency of the challenges we face: the need to do more to safeguard the drinking water, clean air, food supplies, and wildlife upon which we all depend; the need to fight climate change with the natural solutions that our forests, agricultural lands, and the ocean provide; and the need to give every child in America the chance to experience the wonders of nature,” the plan states.

More information on the 30 by 30 plan can be found here. The TRCP participates in a coalition of hunting and fishing organizations committed to conserving global biodiversity called Hunt Fish 30×30.

TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to further our commitment to conservation. $4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue our efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More

For every $1 million invested in conservation efforts 17.4 jobs are created. As Congress drafts infrastructure legislation, let's urge lawmakers to put Americans back to work by building more resilient communities, restoring habitat, and sustainably managing our water resources.