9480792050_e24a2860bf_k-Photo-by-Joe-D-via-flickr-1200-web

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

These programs could serve as a model for other states with a growing tally of landlocked hunting and fishing areas

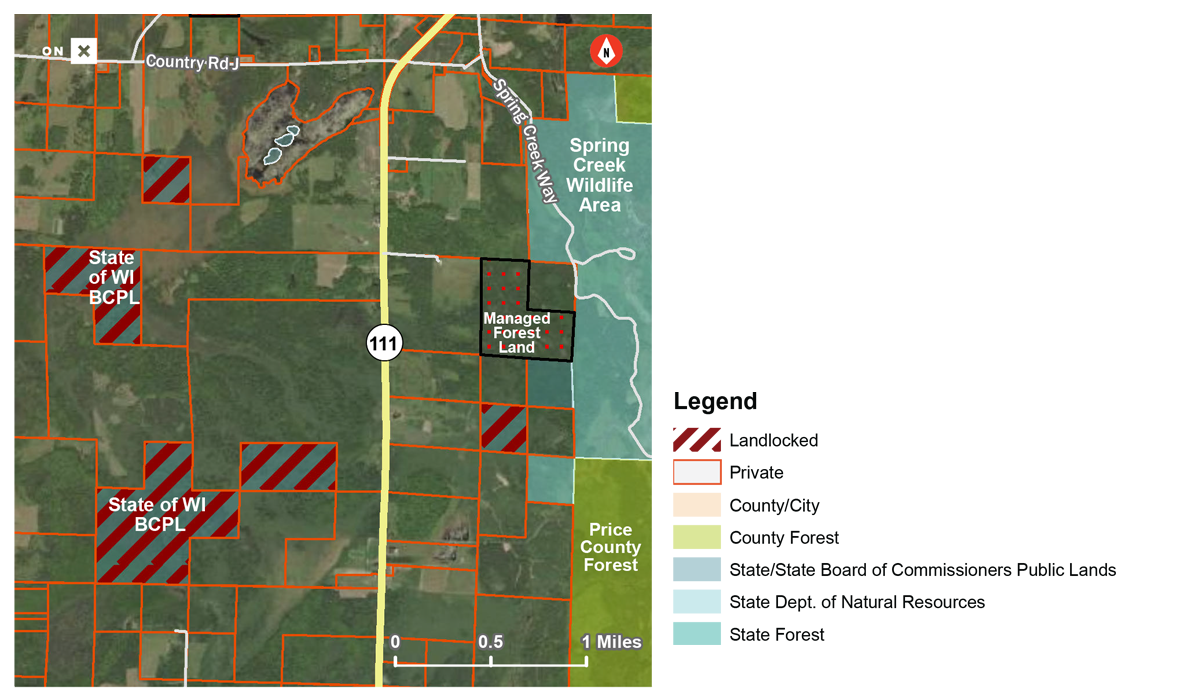

These days, thanks to GPS technology, anyone with a smartphone can take advantage of the hunting and fishing opportunities offered by even the smallest parcel of public lands. But what if you stumble across something like this, where there doesn’t seem to be any legal access to reach it?

You might think it’s a mistake, but there are actually more than 300,000 acres of these landlocked public lands in Minnesota and Wisconsin alone. Across the West, there are nearly 16 million landlocked acres.

Sure, you could knock on a few doors and request permission to cross private land into those crosshatched areas. But if access to public lands like these remains exclusive or temporary, we’re tying one hand behind our backs when it comes to recruiting and retaining the participation of new hunters and anglers.

For a Midwestern hunter looking to hang a treestand for whitetails, set up an ambush for turkeys, or work a woodlot for grouse—especially for the first time—a small or overlooked public parcel could be a game-changer. And easy access to a lake shore or riverbank might give a parent the only place they’re be able to teach their kids to fish for walleye, pike, or smallmouth bass.

Strategically unlocking as little as a few dozen inaccessible acres at a time could mean the difference between a young person having a place to hunt or not. A lifelong passion for fishing—and the conservation funding raised by those license purchases—could hang in the balance.

Landlocked public lands are best made accessible through cooperative agreements with private landowners that result in land exchanges, acquisitions, and easements, but this critical work cannot be facilitated by land trusts, conservation organizations, and public agencies without funding.

When thinking about opening inaccessible public lands, even small projects can offer big benefits. Here are three programs that support these efforts.

The federal LWCF remains the most powerful tool available for establishing and expanding access to public lands and waters. And it just got more powerful, with the recent passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, a bill that fully funds the program at $900 million annually in support of wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation, including $27 million that is dedicated to public access. Importantly, the LWCF is not just limited to federal projects—at least 40 percent of the program must be used for state-driven projects, making it available to help open state- and county-owned lands for public recreation.

Established by the voters of Minnesota in 2008, the Outdoor Heritage Fund is supported through the state sales tax. This program empowers projects that protect, enhance, or restore prairies, wetlands, forests, or other habitat, and—when it meets those primary goals—can also be used to open or expand access to inaccessible wildlife management areas managed by Minnesota DNR’s Fish and Wildlife Division. With an estimated $100 million available in 2022, the Outdoor Heritage Fund is a heavy hitter in support of conservation and access.

Created in 1989, this program exists to preserve valuable natural areas and wildlife habitat, protect water quality and fisheries, and expand opportunities for outdoor recreation. With a budget of $33 million in 2019, Knowles Nelson is a major program that, among other things, can help unlock Wisconsin’s state parks, wildlife and fisheries areas and state natural areas. Knowles Nelson is set to expire in 2022 and will need to be renewed by the state legislature. State decision makers need to know the importance of this program for wildlife habitat and public access.

Both Minnesota and Wisconsin have innovative state programs for conserving habitat and improving access that should serve as valuable models for other states looking to do the same. Support local ballot initiatives and state legislation to set aside these dedicated funds where you live.

To dig into the data we’ve uncovered on inaccessible public lands across the country, click here.

Backcountry Conservation Areas near Missoula and Lewistown will safeguard recreational opportunities and wildlife habitat

(Missoula, Mont.)–The Bureau of Land Management today announced it’s finalizing new Resource Management Plans in western and central Montana that will shape hunting and fishing opportunities for generations to come.

These two plans will guide the future of forest and grassland management, wildlife habitat, fisheries conservation, and outdoor recreation on approximately 900,000 acres of public lands east of Missoula, surrounding Lewistown, and in and around the Missouri River Breaks. In response to requests from sportsmen and women, the final plans include Backcountry Conservation Areas, a new multiple-use framework aimed at conserving prized big game habitat and hunting and fishing areas.

“Thanks to these plans sportsmen and women will experience high-quality big game hunting in places like the Hoodoos and Ram Mountain in the Missoula area, as well as Arrow and Crooked Creeks in central Montana,” said Scott Laird, Montana Field Representative with the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “We appreciate that the Montana BLM listened to the input of many hunters and anglers and adopted Backcountry Conservation Areas in the final plans.”

The Missoula Field Office plan guides the management of local landmarks including the Blackfoot River corridor and portions of the Garnet and John Long mountain ranges. The revision process was formally initiated in early 2016 with a scoping phase and then the draft plan was published in May 2019. Hunters, anglers, the state of Montana, tribal representatives, Missoula County, and other entities spoke up in support of Backcountry Conservation Areas in the highest value wildlife and recreation areas. Those comments are reflected in the final plan.

In the Lewistown Field Office, which encompasses some of Montana’s best elk hunting units in the Missouri River Breaks, the planning revision process unfolded along a parallel timeline to Missoula’s. Similarly, strong support from the sporting community, the state of Montana, and local conservation groups led BLM decision-makers to include Backcountry Conservation Areas in the Crooked Creek and Arrow Creek areas.

“While the Lewistown RMP didn’t include everything we asked for, we are grateful that our comments generated some compromise, said Doug Krings, the Region 4 Chapter Leader for Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. “In particular, the addition of the BLM’s new Backcountry Conservation Areas—which ensure that wildlife and wild places will stay intact and productive for hunters and other outdoor recreationists—is something that all public land owners are pleased to see.”

“The recently released plans are not perfect, but Trout Unlimited appreciates changes in the final Lewistown plan that give greater consideration for the conservation and restoration of rare native trout populations in the Judith Mountains,” said Colin Cooney, Montana field coordinator for Trout Unlimited. “We also feel that this RMP sets a new, much-welcomed standard for stream buffers in the West and one that we are going to work with other field offices to adopt in a region where economic diversity is so important. Specifically, the plan includes ½ mile oil and gas development buffers for all Blue and Red Ribbon fisheries, native trout streams, and streams suitable for restoring populations of Westslope cutthroat trout. We thank the BLM for including this necessary, balanced, and common-sense bar of protection for our most important trout fisheries.”

In collaboration with landowners, local government officials, and other stakeholder groups, several hunting and fishing organizations helped activate sportsmen and women to provide meaningful feedback on the draft plans that was then incorporated into the final proposals.

Photo: Charlie Bulla

Despite the results of the Army Corps’ final environmental impact statement, sportsmen and women still oppose greenlighting the copper and gold mine permit

In 2014, the EPA all but doomed the now-infamous Pebble Mine proposal on the grounds that it would irrevocably damage Bristol Bay’s sockeye salmon fishery. But last week, the Army Corps of Engineers concluded in its final environmental impact statement that the mine would not have a measurable effect on fish numbers.

Now, the Corps could give the green light to dig in the headwaters of Bristol Bay in as little as 20 days, even though its study confirms that Pebble would destroy 185 miles of streams and over 4,000 acres of wetlands in the most prolific sockeye salmon fishery on the planet.

This decision would do harm to:

Oh, and did we mention that Pebble Mine investors wouldn’t even be satisfied with the project as it has been proposed? You see, to get the permit, the applicant substantially shrank the footprint of the mine from what they were proposing five years ago.

Looking at only the current plan, which would extract only a part of the mineral deposit at the site, economists estimate that the mine will lose $3 billion in its first 20 years unless it is expanded. A bigger footprint means more habitat degradation. Witnesses testified on this point before the House Subcommittee on Water Resources and the Environment last fall.

As sportsmen and women, we are once again in a pivotal moment to speak out against Pebble Mine. We know you’ve heard this at various points in the process for the better part of a decade spanning two presidential administrations. (Here’s our appeal after a mildly positive development in 2018.)

But the fact that the proposal was once off the table based on the impact to fish habitat should energize us all to stay engaged. We cannot give up now.

The House voted yesterday to block permitting of Pebble Mine in an amendment to a $1.3-trillion spending package under consideration today. Sportsmen and women need to send a message to senators and the White House and request that national decision-makers intervene to save Bristol Bay.

For more information on Pebble Mine threats, visit savebristolbay.org. Top photo by Fly Out Media.

While the conservation world focused on the Great American Outdoors Act, the administration quietly limited the states’ authority to protect water quality

It feels unfair to be writing about bad news for water quality as we celebrate such a hard-earned victory for public lands this week. Certainly, with the year we’ve been having, all Americans needed a win. But those of us who have been fighting the dismantling of Clean Water Act protections for streams and wetlands needed a morale boost even more. Here’s why:

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency quietly finalized changes to Clean Water Act rules that allowed states to look out for their own water quality as development activities needing federal permits are proposed that may affect the rivers, streams, and wetlands. What is noteworthy from an administration that usually champions states’ rights is how this rule removes state power.

The EPA’s new rule deals with the “401 certification” process, which is an important, if obscure, Clean Water Act authority. To understand how it works, you need to know two things:

At least twice since the mid-1990s, the U.S. Supreme Court has affirmed the broad scope of states’ authority under section 401 of the Clean Water Act. In the first of these cases, the State of Washington successfully required a dam operator to maintain healthy river flows for the resident salmon fishery. That’s just one example of how this process has provided checks and balances to benefit fish and wildlife.

To be clear, the states’ role is not to prevent development. With tens of thousands of certifications issued annually, half the states who responded to an EPA survey reported zero denials. Because projects need certification, the process is usually one where states and applicants work together to find ways for development to proceed without compromising water quality, habitat, or outdoor recreation opportunities.

The new rule would fundamentally change this process, which has existed for 50 years.

Most dramatically, it limits the states to imposing only conditions that relate directly to water quality standards that EPA approves. So, if a bridge were proposed across a stream that currently supports a recreational fishery and provides fishing access, the state could not require that substitute access be provided close by, because EPA does not do this work.

States can no longer institute certain flow requirements—like Washington did to save its salmon—or require a permittee to build or maintain fish passage, even when the permitted activity would fragment an intact fishery’s habitat.

And states will no longer be able to require water quality protection for the streams and wetlands that the federal government no longer protects under the new “waters of the US” rule. (Here’s my post about that.) According to Trout Unlimited scientists, this is 50 percent of the nation’s stream miles and 40 percent of wetlands, like the prairie potholes of the Upper Midwest.

The rule finalized last week also tightens timelines for the states to take action. States issue most of their certifications in less than six months, but large complex infrastructure reviews take more time. It is appropriate to ask regulators to work quickly, but this new rule shifts the power to applicants. The clock starts to run when applicants first put in a basic request—not when a state receives a complete application, with all the information needed for analysis and decision.

Why these changes? In 2019, in Executive Order 13868, President Trump directed the EPA to change the certification process “to encourage greater investment in energy infrastructure.” Regardless of the importance of this policy, it is unrelated to the only objective of the Clean Water Act, to restore the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of our nation’s waters.

The 401 certification change will almost certainly mean less clean water for fish and wildlife, especially when added to the administration’s rule rolling back environmental reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act, also finalized last week, and the rule I mentioned shrinking Clean Water Act protection by almost half.

During debate over the latter, the administration argued that the states could use their authority to protect the headwaters and wetlands that the federal government would no longer regulate. But this latest change constrains the states’ ability to do just that.

While EPA takes contrary positions regarding state authority, the beneficiaries of these rules are the same—those who want to build pipelines without having to safeguard fish and wildlife. These developers also win under the NEPA rule changes.

Sadly, the losers may be those of you reading this blog.

TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to further our commitment to conservation. $4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue our efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More

Sign up below to help us guarantee all Americans quality places to hunt and fish. Become a TRCP member today.