When it comes to the Mississippi River, coastal residents struggle to find a balance between creation and destruction

Over the last 10,000-plus years, as the mouth of the Mighty Mississippi shifted back and forth across the central Gulf of Mexico coast, sediment dropped out and formed a mix of rich, watery alluvial lands crossed and dotted with bayous, lakes, and swamps that eventually give way to marshes and barrier islands.

Since explorers planted a French flag in those soils in 1682, there has been a constant struggle to tame the river and balance the needs of flood control and navigation with the ecological needs of those wetlands and swamps and the fish, wildlife and people who live there.

The struggle intensified in late 2018 through the spring of 2019 as more rain fell in the Mississippi River Valley than at any other time in recorded history.

Levees built in the mid-19th to the mid-20th century protect communities during the average spring flood. But when extraordinary flood levels threaten New Orleans, the Army Corps of Engineers must direct as much as 20 percent of the river’s more than 1 million cubic feet per second flow rate through the Bonnet Carre’ Spillway and into Lake Pontchartrain, north of the city.

The levees, while saving communities and industries, also cut off the vital, wetland-sustaining annual water and sediment supplies. The consequence has been the loss of nearly 2,000 square miles of fish and wildlife-producing marshes and swamps in the last century, making communities more vulnerable to storm surges from the Gulf and threatening Louisiana’s unrivaled fish, waterfowl and wildlife production.

The State of Louisiana has responded to that land and habitat loss with a coastal restoration and protection master plan consisting of levees, floodgates, barrier island and marsh restoration as well as gates in the river’s levees, called “diversions” that will send sediment-laden flood waters back into the marshes.

The recent, unprecedented freshwater flush across the northern Gulf from the Mississippi River, plus flood-stages on the Pearl River and the Mobile River Delta, sent many commercial and recreational fishermen scrambling to find speckled trout, shrimp, crabs and oysters displaced or, in some cases, killed by the flooding. Local elected officials have asked the federal government for fishery disaster assistance to help address the business losses.

While catches of speckled trout, white shrimp and crabs rebounded in the Pontchartrain Basin after the spillway was closed in July 2019, and redfish and bass catches stayed strong throughout the flood, the spillway opening and other flooding has some in Louisiana and neighboring Mississippi questioning if the planned diversions to save and sustain coastal marshes will have similar impacts.

“The flooding we saw was unprecedented and the Corps of Engineers had no choice but to open the Bonnet Carre’ when the waters threatened New Orleans,” said Brian Lezina, the Planning and Research Division Chief for Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. “But, the way that spillway works, by moving 200,000-300,000 cubic feet per second into the open and relatively deep waters of Lake Pontchartrain and then into Mississippi Sound and the Gulf strictly for flood prevention is not how a diversion built specifically to benefit marsh and build habitat is going to function.”

HARD CHOICES

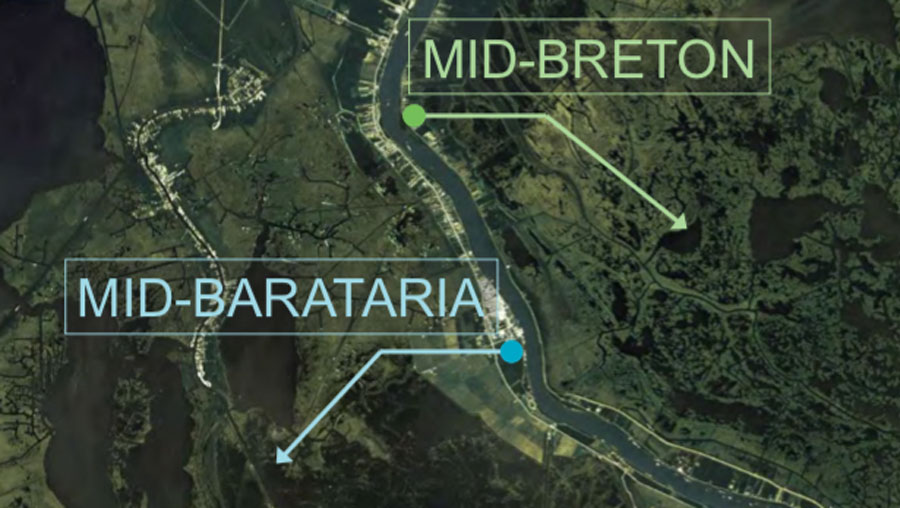

The Louisiana Coastal Master Plan calls for two sediment diversions south of New Orleans, one west of the river called the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion and one east, the Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion. Both are being designed with a maximum flow rate of 75,000 cubic feet per second, far less than the Bonnet Carre’. They are also designed to operate when sediment loads are at their highest in the river, generally from late winter through late spring, to maximize land-building, but at lower flow rates when suspended sediment wanes. Operation plans would allow saltier conditions to return from early summer through late fall each year, the way the river would generally behave.

Lezina and his colleagues have conducted more than 100 public meetings in the last four years with various stakeholders to try and address concerns about the projects and discuss the possible positive and potentially negative affects to fisheries. He said data suggest natural ridges and the small volume of water from the Mid-Breton Diversion compared to the volume of salty waters in the Gulf means different impacts than a Bonnet Carre’ opening.

“Capturing that suspended sediment in the river’s current is essential to sustaining and building wetlands and also preserving the crucial habitat that blue crabs, shrimp, speckled trout, redfish, waterfowl and many other estuarine animals need,” Lezina said. “The majority of popular commercial and recreational estuarine species have evolved with the seasonal inputs of sediment, freshwater, and nutrients. The habitats they rely on for survival, such as vegetated mudflats and marshes rely on that cycle as well. We can control the flow rates of the diversions to mimic the estuary in the same way the river would have done without the levees cutting the system off.”

Many commercial and some recreational fishermen in the areas that will be most affected by the diversions have opposed construction outright despite project openings that are a decade or more away and the crippling coastal land loss of the last century.

Captain Charlie Thomason operates a fishing lodge and guide service east of New Orleans in the town of Hopedale. Areas he fishes will be in the outflow area of the Mid-Breton Diversion. He said he doesn’t completely oppose using the river to rebuild marshes but questions the need for such high flow rates and if his business can survive the seasonal changes to the fishery.

“You look at all the marsh we’ve lost just in the last 20-30 years and there’s no question that something has to be done to address it, but I think the diversions in the Master Plan are just too large,” Thomason said. “The velocities may hurt our marsh and it will certainly change our fisheries half the year. Our clients want to come here to catch redfish and speckled trout year-round and what we’ll be faced with is a fishery where we’ll have trout to catch in the late summer and fall but not the other six or seven months. Our clients will take their business to other places and not come back.”

Thomason said he thinks the Master Plan does a good job of prescribing marsh creation and barrier island projects built with dredges, but wants any diversions to be closer to the levees, smaller and designed to extend out Gulf-ward as sediment is deposited.

Captain Ryan Lambert runs a guide service and lodge 30 miles south of Hopedale in Buras where he focuses on redfish and speckled trout throughout the year and waterfowl hunting in the late fall and winter. He has been one of the state’s most outspoken proponents of sediment diversions despite the difficult conditions caused at times by the river. East of Buras is one of a handful of places in Louisiana where natural bayous and crevasses connected to the river are depositing sediment and building land each year.

“We have to have that sediment and that water coming out of the river to build our land and habitat,” Lambert said. “With all of the cuts and passes east of the river, we are dealing with hundreds of thousands of cubic feet of water when the river is high, but we still fish there because that’s where the habitat is good and where we can catch fish.”

He contrasts that with the west side of the river where there is no connection to the Mississippi River and the marsh has subsided and been battered and eroded by hurricanes.

“I used to spend 90 percent of my time fishing the marsh west of Buras, but now it’s nothing but open water for six miles between me and the Gulf,” Lambert said. “Without that marsh, the mudflats and the grass, our juvenile shrimp, fish and crabs can’t survive. We must have that water and sediment feeding our habitat. Without it, we have no fish. We have no future.”

Living here on the coast and being a third generation commercial fisherman I am for using every tool in the tool box to at least try to do something about the erosion. I’m 60 years old and just about all of the marsh here has turnedinto open water in my lifetime. If nothing is done it will all be gone before long.