There is a lot of misinformation out there, so we had three experts clarify exactly what will and won’t help stop the spread of CWD

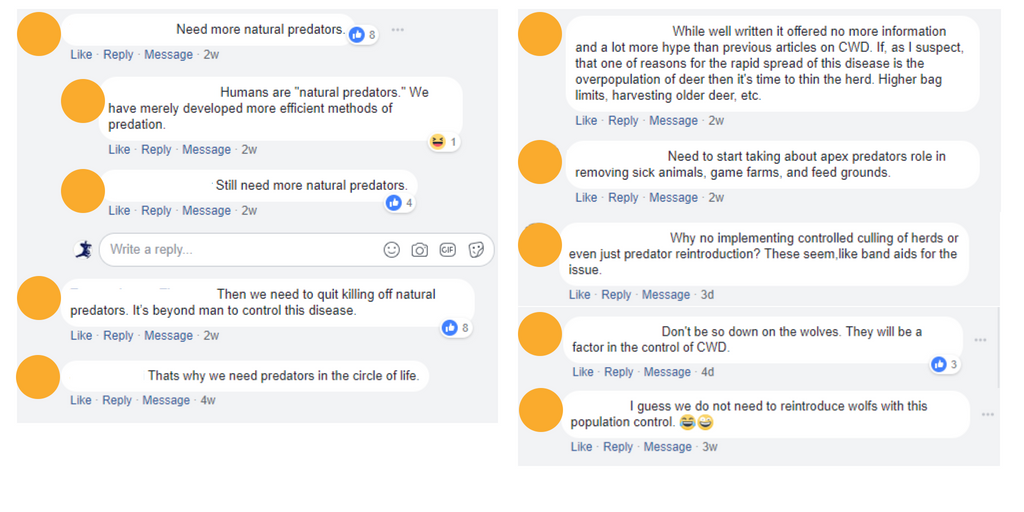

Since the TRCP first began advocating for real and meaningful steps from national decision makers to control Chronic Wasting Disease, we’ve noticed that this emerging epidemic seems to be the new climate change. While the topic has become unnecessarily politicized in many online forums, some common misconceptions could be keeping many hunters from taking urgent action.

Many of us get reliable information from our friends and social networks about where to go hunting and fishing, what gear to buy, and what techniques to try. But on an issue that is this important to the future of deer hunting in America, we’d rather have hunters hear directly from the experts. So we brought together three of them to tell us honestly if any of these CWD-deniers have a point.

Here’s how they responded—calling on science, field experience, and just good sense—to the most common gripes we see from skeptics.

Gripe #1: “Chronic Wasting Disease has been naturally occurring as long as there have been deer—it is not new and the threat is no more imminent today than it was decades ago.”

RICHARDS: While it is challenging to prove either way, there is little evidence to support the idea that CWD has existed as long as deer have. The CWD distribution pattern observed in several geographic regions suggests disease was introduced in a modern timeframe, became established, and subsequently spread in a radial and progressive fashion. In several areas where the disease has been documented the longest and where prevalence is highest, population impacts have now been documented. If CWD had “been around forever,” it seems likely that these impacts would have been documented in the historical record.

THOMAS: CWD was first identified in the United States in 1967 in Colorado—so, no, it’s not exactly new. But it’s clear that the threat of CWD is growing at a faster rate each year. It has gradually spread around the Western states and into Canada, and in 2002, it was found east of the Mississippi River for the first time in Wisconsin. Mississippi recently became the 25th state to find the disease. Not only is the disease spreading across the United States—through the legal transport of live deer and elk and the natural movements of wild deer—it is also putting down deeper roots in affected areas. In one county in Wisconsin, more than 50 percent of adult bucks tested came up positive for the disease, and that rate has climbed faster each year that testing has been done.

CORNICELLI: It’s also important to note that state wildlife agencies have a moral and legal obligation to manage wildlife populations for the long-term. So, whether or not you believe that this threat is “imminent today”—which I do—it’s my job to focus on the future of these species. This concept is often difficult for hunters and many others to understand, because in today’s society we live so much in the present.

Gripe #2: “I’m not worried about CWD, because the disease has never been found in humans.”

THOMAS: It’s true that a link between CWD in deer and illness in humans who consume deer has not been proven. However, because similar diseases, such as mad cow disease, have made the jump from cattle to humans, both the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control urge caution. A recent review of 23 different studies of CWD potential in humans concluded that “future discovery of CWD transmission to humans cannot be entirely ruled out on the basis of current studies, particularly in light of possible decades-long incubation periods for CWD prions in humans.” That’s why the QDMA urges hunters who kill deer in CWD zones to have each deer tested for the disease and wait for test results before consuming the venison.

CORNICELLI: Why take the risk? I am astonished at the low number of deer tested in Wisconsin counties with the highest concentration of CWD. It indicates that hunters are perfectly comfortable feeding infected venison to their families. Perhaps because at this point in time we aren’t seeing human disease, people don’t think it will ever be an issue. However, I follow the CDC guidelines, and so do most of the people I associate with.

Gripe #3: “I’m not worried about possibly consuming venison from a CWD-positive deer, because I don’t eat my meat rare.”

RICHARDS: Disease-associated prion proteins are very resistant to breakdown by heat. As such, cooking venison from a CWD-positive deer, regardless of how “well done” it is, will not appreciably deactivate prions.

THOMAS: One study found that prions are still viable after being incinerated at 1,562 degrees Fahrenheit. “Well done” won’t even scare ‘em.

CORNICELLI: Perhaps Hank Shaw can write a book on CWD-venison recipes? “Drogon, Rhaegal, and Viserion: The complete guide to cooking venison ash.”

Gripe #4: “We should just allow the natural predators of deer and elk to take care of the CWD problem.”

THOMAS: CWD incubates in whitetails for an estimated minimum of 16 months and an average of two years before the deer become “clinical.” This is when they begin to show symptoms and would be more susceptible to predators in their weakened state. Higher predator numbers would not control CWD, because adult deer are infectious to other deer throughout the entire incubation period.

Gripe #5: “Can’t we just shut down all the deer farms? Problem solved.”

RICHARDS: Even without the captive cervid industry, CWD will likely continue to grow and spread—it is now well-established among some wild cervid populations. Reducing or eliminating human-assisted movement of CWD, on the other hand, has been identified as a key preventative measure.

CORNICELLI: Even if we agreed it was the right decision, it would be difficult. The captive cervid industry is well-connected politically and has been very effective at promoting their importance to the world economy. Conversely, hunters do a poor job organizing and can sometimes seem more interested in their short-term benefits—antler point restrictions, season timing, and bag limits—rather than the long-term viability of deer populations. This is how deer farming, a small industry at $17 million a year in Minnesota, can overwhelm something as economically important as statewide deer hunting, worth $500 million a year in Minnesota.

Then there are hunters who buy into the captive cervid industry propaganda, saying, “This is not a big deal, we can use genetic manipulation to solve this problem, and captive cervid testing is 100 percent accurate.” None of this is remotely true.

Gripe #6: “You are exaggerating the scope of the CWD problem and fearmongering to raise money.”

THOMAS: Perhaps the most dangerous thing about CWD is how slowly it eats its way through a deer population. It does not create stacks of dead deer that are visible to hunters. In fact, many hunters in CWD zones never see sick deer. While CWD is always fatal to any deer that gets it, they may not show symptoms or appear sick for up to two years. Meanwhile, they are spreading it to other deer and depositing prions in the environment through their saliva, feces, and urine. So the situation may not appear alarming, even inside CWD zones.

The alarming part is what will happen to these deer populations over the next 10 years, 20 years, and beyond. There is no vaccine or cure for CWD, it is 100 percent fatal, and we still don’t know how to eradicate it from areas where it has been established. These are the facts—not exaggeration—and this is a recipe for a slow-moving disaster. Action must be taken now to prevent the further spread of CWD and to focus research on finding solutions.

Gripe #7: “CWD is such a huge problem, there’s nothing that any of us can do at this point.”

CORNICELLI: I don’t share that fatalistic view, and I think there’s still a lot we can do—although I admit that in several places (parts of Wisconsin), the horse has not only left the barn, it died some time ago. As an agency manager for more than 25 years, I would be negligent in my responsibilities, as would my colleagues, if we threw up our hands and gave up. But wildlife management authority is not created equal in every state. Some states have the regulatory authority they need to find solutions, but often state legislatures are unwilling to take the necessary steps to do what the state wildlife agency believes to be right.

THOMAS: Yes, there is, and hunters can contribute. When you travel out of state to hunt, find out if you’ll be hunting in a CWD zone, learn the local regulations about transporting parts of your deer carcass. If you learn of someone planning to illegally transport live deer, report them to law enforcement.

Prevention is the only effective method for dealing with CWD, and hunters in unaffected areas must become engaged in the prevention effort. If you don’t have CWD in your woods, you don’t want it.

Top photo courtesy of the National Deer Association

The argument against allowing natural predation by wolves and cougarsm to see what effect it has on the spread of CWD, is very weak. It is not adequately supported by empirical evidence. Do deer and elk only live for only two years as general rule? No. If they live longer than that, can they still be contagious to other deer and elk? Yes. Do we know for certain that natural predators are unable to detect the presence of infection in cases where we humans cannot – that is, while it is “incubating”? No. If I am wrong, please correct me. If I am not wrong, then aren’t we at least owed a serious discussion on this issue instead of shades of the old irrational prejudice against large carnivores? I should hope so.

I don’t understand your point about predators being able to detect the disease. The point is that predators prey on physically weaker specimens, not just sick ones. They prey on sick ones because it makes them physically weaker. Also, if they were able to detect the disease before it manifested outwardly, might they not be more inclined to let the animal be? Again, I don’t understand why you think a predator who could tell the difference between a sick and a healthy animal would choose the sick one just because it’s suck but still fully capable physically?

Thank you for the simple and straightforward update. We need to keep this topic on the front burners of every state wildlife agency. The more that agencies focus on the detection and management of this disease, the more likely it becomes that we will develop effective means of dealing with CWD at the population level in our deer, elk and moose populations.

U think GMOs are growth hormones?

GMO’s started about the same time that deer started to show up with CWD–anybody research that,growth hormones effect many things

Very good point and likely cause. Altering genes in ways unable to happen naturally is extremely dangerous to all life.

GMOs of plants arrived in the ’80s – mice in the mid ’70s. CWD showed ip before that in CO…likely no correlation.

On a related note, stork populations increased dramatically, followed by a dramatic increase in the human population. Causal relationship or coincidence. Also, don’t confuse genetic modification with hormone therapy.

Thanks for clarifying these very important misconceptions with commentary from experts in the field. I would also recommend people listen to the MeatEater Podcast with Bryan Richards.

Simply put, readers that deny the severity of CWD., need to identify which articles they are reading that suggest this. Without such evidence its only guess work. There is info. on the web done by doctors and labs that say otherwise.

here’s my thoughts. it seems that the CW problem has increase in areas that have been affected by tick increases. tick increases also seem to be caused by changes in climate. I have also seen noticeable less possums. possums help decrease the ticks. do bats figure into decrease of ticks.seems to me if we can increase the animal population of those that eradicate the ticks, the CW problem might actually DECREASE. my two cents anyway.

This is an article that needs to be shared in an attempt to enlighten and educated hunters and venison lovers all over. My home state of Illinois is trying to reduce deer numbers to attempt to reduce the spread, but something that I have not heard any state trying to do is eliminate the use of scents and urine. I have read that CWD increases in potency once it adhears to clay particles in the soil. Whether or not it increases, it does not disapate, therefore but hunters setting up mock scrapes, running drag lines, and even spraying tinks 69 all around their stand before a sit could be putting their whole herd in danger.

Seems odd that captive farms are ostracized yet nothing is mentioned about baiting. Wild deer can spread prions at bait sites, yet wildlife agencies are unwilling to ban the practice. Guarantees the spread.

If chicken feed is used in deer bait sites, woukdnt ghat be hazzardous to the deer if recycled protein from beef slaughterhouses is contained in it?

Please get experts who’s jobs do not rely on CWD becoming more prevalent. Mr. C seems to have a bur under his saddle about protecting everyone’s safety. Mr. C that is not your job! I’ll protect myself thank you. You remind me of Ronald Reagan joking “I’m from the government and here to help you.”

The big issue here is captive grow wild animals. End of story.

Jerde, when is the last time you have been infected by Typhoid or cholera? I think the government did a good job there. Don’t be ignorant about the history of communicable disease even if its cross species.

Boy, by that logic, you should also stop going to the doctor, because his/her job also relies on you being sick; therefore, there is no incentive to cure your ailments. Another kid left behind.

Thanks for a good article that should give some brain-food for any hunter/conservationist who rightfully should be concerned both with the health of cervid populations as well as human health implications. A couple of thoughts: On game farms – I-143 , a citizen initiative in MT passed to shut down Game farms for shooting operations while still allowing hides, horns(antlers), and food operations for the remaining operators. 1 CWD incident previously in 1996 (approx.) found in a pPhilipsburg game farm opened our eyes. CWD reports from Wyoming were creeping closer and closer to MTs border on the south; I-143 passed in 2000. Coincident with re-introduction of large charasmatic predators in Yellowstone occurred in ’96… I became employed with MT Wildlife Fedration in 2001 and CWD encroachment was anticipated soon afterward, yet the first documented case discovered near the WY border in 2016, more than 15 years after the “imminent occurence” was supposed to happen. I suggested that wolves may impact the spread, as we in conservation do insist that they do prey upon the weakened and sick. Albeit these deer in such a state have been infectious long before symptoms, removing them is alweays beneficial; some leaders scoffed but now accept that large carnivores help balance the equation. So, combine a healthy predator base with reducing movement of captive bred ungulates by outlawing game farms has had its impact. I am a bit concerned that the game farm aspect was diminished in this article. Even though the numbers of farms is low the potential spread and impact is not, in any way, a small one. All-in-all, thanks for keeping the co0nversation alive although it is depressing to observe how little we can do to stop it. Doing what we can do is imperative.

I would hope this type of info is shared throughout the social and all types of media. Every little bit helps to educate hunters on the severity of the problem. In addition I would like to see the experts thoughts on how(and what impact) hunters actions and practices play in control, both reactive and proactive. Specifically, harvest of 1 1/2 year old bucks; baiting,feeding and food plots; extent of testing beyond a core or management area; transporting carcases; disposal of entrails and skeletons and etc.

What does moderation mean?

Luckily CWD not yet reported in Oregon but may be on its way. Wolves have been documented to roam hundreds of miles, not territorial like cougar. Could the wolf eating a diseased deer become infected and become a vector to increase the spread of CWD?

Biochemical studies revealed the presence of partially proteinase K (PK)-resistant fragment and immunohistochemistry displayed staining for PrPSc in the cerebral cortex. Importantly, interspecies transmission of canine PrPSc derived from RWD3 brain homogenates following inoculation of hamsters led to signs of prion disease and replication of PrPSc in brains, spinal cords and spleens of these animals.

These findings if confirmed by further cases of prion disease in canidae and regardless of the origin of the disease would have a major impact on animal and public health. http://chronic-wasting-disease.blogspot.com/2018/03/cervid-wild-hogs-coyotes-wolves-cats.html

How much of the spread is related yo deer densities? I game managers are managing for hunter success rather than herd health doesn’t that need to be addressed?

A great article that is much appreciated, but all articles like these ever say is “have your animal tested”. What about areas where the state game agency is not testing for the disease and local veterinarians aren’t willing to collect samples (which happened to me on a trip to Kansas)? How then is a hunter supposed to have their deer tested? Could you please write an article describing all of the methods we as hunters could use to collect samples and how and where we can ship them?

STILL wondering why what appeared to be the most promising branch of research of prion diseases was pushed aside. Seems to me that the spiroplasma theory was more or less fiscally isolated because of mere egos and politics; bandwagons of half informed opinion do little to further genuine science.

Thanks for posting this theory. I have read a lot of studies on prion theory, and hadn’t even heard of spiroplasma theory. I certainly am at the stage of barely being able understand this science, the spiroplasma theory definitely seems to have merit.

Reducing herd numbers was an effective means of keeping CWD at relatively low incidence in Colorado. The herds are expanding again, yet quotas have not been increased. I fully expect another “crisis” because of this. Healthy herds of deer and elk are better for long term management goals.

Excatly in numbers how much has the deer and elk population shrunk in Colorado do to CWD? What percentage of wild cervids are now dead in Colorado, since 1964 there must be some documented numbers by now?

I’ve written a couple of articles investigating CWD in the context of Colorado and the potential impact to prion transmission predators may have:

“[Margaret] Wild [chief wildlife veterinarian in the Biological Resources Division for the National Park Service (NPS) and chief author of a study hypothesizing wolves might limit CWD] says one of the best ways to target deer or elk infected with CWD may not be by using human eyes but with the eyes of a wolf who has evolved over eons to know the most susceptible deer or elk to prey on. “And if you can do that over time then the disease will slowly fade out,” Wild says, which may prove critical because there is no cure or vaccination for CWD.” http://www.boulderweekly.com/news/will-coloradans-free-wolves-states-public-lands/

“A 2009 study led by the Colorado Division of Wildlife (now the Wildlife section of CPW) in Northern Colorado found that mountain lions actively selected CWD-infected deer when targeting adult mule deer as prey, whereas hunters tended to select and thereby remove deer not infected with CWD.” http://www.boulderweekly.com/news/off-target-series-kill-mountain-lions-already-gone/

Predators are capable of transmitting and dispersing prions over their range. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4964857/

So, from your article the number one way to slow the spread is via the deer farm industry, but they are “politically well connected”. Another political thing Lou? Whatever happened to your moose with global warming stuff? It took a while but eventually when Mech himself came out with very convincing data everyone agreed that occam’s razor cuts deep. With all due respect how do you think the politics will work out when people figure out you just sat on the issue in fear of politics? I mean you already blew it with the moose, now deer? Soon you’ll run out of large ungulates.

I just returned from a Nebraska deer hunting trip. My MD buck tested positive for CWD. Having run petroleum labs for 35 years and being well aware of lab protocol makes me wonder? Are these labs certified? Do they exchange samples for cross checking and quality verification. How do any of us know that they know what they are doing? People are people and everyone has a bad day which could result in a bad finding. I am not ” In awe” of results that are collaborated, Since it’s discovery in 1967, we sure haven’t made much headway in coming up with answers.

Climbing the Hill of Denial

With the geographic range and prevalence of CWD expanding throughout the country there is more and more talk within the hunting community about what this means. That is a good thing, a really good thing. Hunters becoming more engaged and more knowledgeable about the resource they are so passionate about can only lead to better management. But there is a monumental hill we must climb first, and it’s a big one…it’s the hill of Denial.

Whenever something you love is threatened it is only natural to begin questioning why and looking for answers. Unfortunately, when the news on the health of a loved one is bad, people often look for something to believe in even if it means listening to less reliable sources. They grasp at whatever information they can find to make the disease go away. CWD is no different.

Questions are good, denial is bad. And unfortunately, denial is running rampant in some segments of the hunting community. One thing hunters are hanging their hopes on is this belief that no deer has ever been confirmed to have died in the wild from CWD. Some are wanting a table that shows the exact numbers of deer that have died and have tested positive for the disease. The problem is they are asking for something that cannot be produced. This bolsters their position of denial and leads them to believe the disease is not really killing animals.

So, to their point, why can’t such a table of wild CWD deaths be produced?

There are a number of reasons. And they’re actually pretty simple to understand if you just take the time to think about them logically.

First off, we know CWD kills deer. It’s been proven in multiple studies. Sometimes it acts fast with deer exhibiting clinical signs within a few weeks but sometimes it could take as long as a few years. This is problem number one.

We know deer in the wild the have CWD are going to die prematurely but we don’t know when, so sampling them becomes near impossible. This is because tissue samples usually only last a few hours upon death. Temperatures above freezing cause tissue decay and temperature below freezing can ruin the sample, hence you only have a matter of a few hours to pull a sample once the deer dies. How many people here have walked upon a fresh deer carcass where the deer has died naturally and is still warm? Few, if any. And if you have, you probably stumbled upon it by accident. Biologists simply cannot walk around the woods hoping to stumble upon dead deer.

Immediately some people will point to EHD and talk about how those deer are found every year. That is true but in the case of EHD we have a pretty good idea when the deer are going to die (late summer) and where they are going to die (near water). But even those deer do not get tested much. In 2007 when EHD wreaked havoc in Tennessee, it was estimated over 65,000 deer died within a very short period of time, therefore, dead deer were easy to find. Guess how many samples were tested? About a half dozen. Finding a sick deer within hours of its death when it can die at any point in time throughout the year is near impossible.

But here’s the other issue, problem number two. CWD is a disease that oftentimes causes mortality from secondary issues. In other words, it changes the behavior or health of the animal causing it to succumb to other types of mortality. For example, a deer with CWD is more likely to be preyed upon, die of starvation, drown, or get hit by a vehicle. Think of a human with severe Alzheimer’s or dementia wandering the streets each and every day. Odds are something bad is going to happen to that individual.

This increased mortality due to other causes is the primary reason an infected deer’s life expectancy decreases substantially. This is also where hunters get hung up in the state of denial. Their claim is the disease did not actually kill the animal.

This is an argument we cannot win simply because they are correct, the secondary issue does oftentimes kill the animal. But thinking it is natural for a healthy deer to starve to death in mid-summer is the epitome of denial.

The craziest argument of all are the hundreds, if not thousands, of sick deer that have been killed throughout the nation that have tested positive for CWD. Many hunters claim the lead bullet killed the deer not the disease. Once again they are correct, and once again they are in denial.

But there is hope.

Once a hunter clears this hurdle of denial and begins to understand what the disease is doing to their herd, they can then begin managing to improve the health of the deer on their property. Although there may not yet be a cure, and may never be, there are things that can be done to slow the spread of the disease and lessen the impacts from the secondary issues.

Remember, knowledge is power. Use it to inform, not to deny.

Daryl Ratajczak, Former Chief of Wildlife and Big Game Program Coordinator, Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency