8552014911_cd4769d5b9_h-1200-web

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

Forage Fish Conservation Act would improve recreational fishing opportunities

U.S. Representatives Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.) and Brian Mast (R-Fla.) have introduced legislation to promote responsible management of forage fish—the smaller bait fish that larger sportfish rely on for food.

The Forage Fish Conservation Act would address a decline in forage fish populations, strengthen sportfish populations, and support better recreational fishing opportunities. Forage fish populations have been declining due to numerous pressures, including changing ocean conditions, and this legislation takes steps to support a more robust marine food web.

“This legislation uses sound science to preserve our nation’s fishing economy,” said Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “Declining populations of forage fish hurt the entire marine ecosystem and sportfishing opportunities. This bill will help prevent overfishing and create sustainable fisheries. We appreciate Representative Dingell working with a broad coalition to advance conservation efforts across the country.”

The Forage Fish Conservation Act ensures that enough forage fish remain in the water by:

The Forage Fish Conservation Act is also co-sponsored by Representatives Matt Cartwright (D-Pa.), Fred Upton (R-Mich.), Billy Long (R-Mo.), and Jared Huffman (D-Calif.)

Photo by the Chesapeake Bay Program via flickr.

An organization that provides all-expenses-paid flyfishing trips to combat veterans ensures that participants go home with so much more than campfire stories

With the inspiring success of organizations like Project Healing Waters and Casting for Recovery, many sportsmen and women are aware of the emotional and physical healing power of the outdoors. But when Dan Cook, formerly a financial executive, set out to establish Rivers of Recovery in 2009, he wanted to prove that the act of fly fishing—not to mention the camaraderie of bringing veterans together in remote and beautiful places—actually made a biological impact on returning military service members.

“They analyzed urine and saliva samples from the program participants before, during, and in the 6, 9, and 12 months after a fishing trip,” says Amy Simon, who started out as a Rivers of Recovery volunteer before running the organization with Cook and eventually stepping into the executive director position in charge of all operations and program curriculum. “The tests showed lower cortisol levels after fishing, and the participants reported sleeping better, having lower stress, and, in some cases, going off medications they’d relied on for their mental health. Dan really wanted to go beyond starting an organization and actually prove we were making a difference.”

Thirty veterans took part in their first trip out of Dutch John, Utah, and these days the organization runs programs in eight different states, touching countless lives in the process. Over time, they discovered that building an experience within an existing community of local veterans was very beneficial, compared to flying a group out to Utah. This way, relationships could be built and maintained after the trip, and supportive local businesses, fishing guides, yoga instructors, and other volunteers remained in the participants’ community as resources.

“We found we could leave behind a footprint of support,” says Simon.

She was also instrumental in launching RoR’s first trips exclusively for female veterans, who may be dealing with entirely different issues than men when they return home. In the October 2017 issue of DUN Magazine, U.S. Army veteran Monica Shoneff explained, “A lot of female vets get out of the military and jump back into caring for a family. Self-care becomes a low priority. Where men can focus on themselves, we get lost.”

Now an RoR volunteer, Shoneff estimates that 95 percent of the women combat veterans she’s met have experienced sexual trauma during their military careers, leaving many to deal with anxiety, depression, and high rates of PTSD.

So, how does an all-expenses-paid flyfishing excursion help? “You have to focus on what you’re doing,” she tells DUN. “It takes away from time to ruminate and think about past events or worry about the future.” Simon adds that the activities on the water and in camp start to generate trust, bring vets out of their guarded stance, and open lines of communication. “By the time you leave, you feel like you’re part of a family,” she says.

In many cases, none of this would be possible without public lands, says Simon, so conservation and the healing power of the outdoors go hand in hand. “If those resources were not available, we would not be able to succeed,” she says. “How can you not want to take care of these places that give so much to someone like a wounded veteran?”

Another active volunteer and RoR Board member, Jim Mayol, says he sees public lands issues differently now that he’s witnessed the transformation of program participants. “I see them before the trip, after, and in social settings, and there’s no doubt that the outdoors has had an impact on their healing,” he says. “It’s a no-brainer for me to advocate for these places now, where I may not have given it a lot of thought before.”

To learn more about Rivers of Recovery and how you can get involved, visit riversofrecovery.org.

All photos courtesy of Rivers of Recovery.

TRCP’s “In the Arena” series highlights the individual voices of hunters and anglers who, as Theodore Roosevelt so famously said, strive valiantly in the worthy cause of conservation

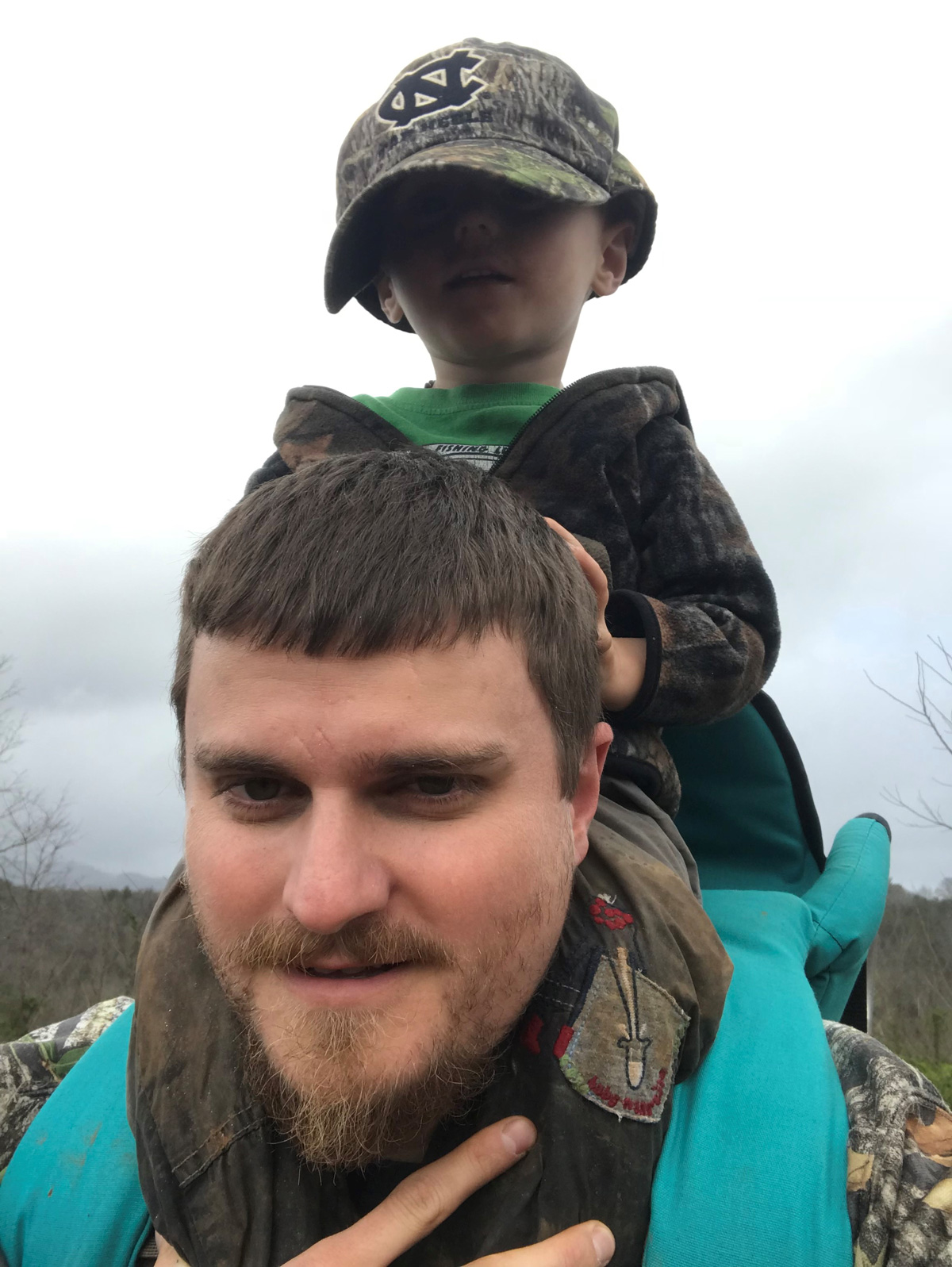

Hometown: Leicester, North Carolina

Occupation: Soil and water conservation district director

Conservation credentials: Helps landowners use Farm Bill conservation programs to improve soil health, water quality, and wildlife habitat

When you’ve idolized legends like Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone since childhood, chasing adventure through our public lands might be enough of a goal. Tyler Ross takes dedication to the outdoors one step further. His day job helps bring Farm Bill conservation programs off the pages of the Federal Register and onto the working lands of his home state so that fish and wildlife resources are just as legendary for the next generation.

Here is his story.

I did a lot of reading when I was younger, and all my heroes from books either hunted, fished, or farmed. I wanted to be with Davy Crockett on a bear hunt or walking next to Daniel Boone as he stalked a deer in Kentucky. So, naturally, I started getting outside and chasing whatever I could.

These days, that’s still my idea of a good time. Even though I know it isn’t possible, I would love to bowhunt red stag in Scotland or Ireland—even better if it was with a recurve. I bet it would feel like I was part of Robin Hood’s Merry Men in Sherwood Forest, chasing that beast in its native habitat.

This past year, I went with my four best friends on our very first DIY elk hunt out West. I called in two different bulls for my buddies, and one ended in a successful harvest. That time with them, in that area, enjoying our Creator’s bounty, is something that I know will be unmatched for the rest of my life.

In my area, Farm Bill conservation programs benefit sportsmen and women in many ways. On the public land side, the recent expansion and utilization of Good Neighbor Authority helps keep public lands in public hands and gives land managers the tools to conserve these places for those who come after us.

On the private lands side, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program is really helpful for increasing wildlife habitat and pollinators. We don’t have many Conservation Reserve Program acres in North Carolina, so EQIP and the Conservation Stewardship Program provide many of the habitat benefits here.

We had some big wins in the latest Farm Bill, particularly with EQIP. Lawmakers increased the portion of the program that must be used for practices that benefit wildlife from 5 percent of funds to 10 percent. That’s huge!

It was also awesome to see soil health practices embraced in multiple programs. And the expansion and re-authorization of the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program on U.S. Forest Service lands is something that I hope continues in future farm bills.

During implementation of the 2018 Farm Bill, I would love to see an emphasis on Working Lands for Wildlife, the USDA’s effort to improve agricultural and forest productivity while enhancing wildlife habitat on working landscapes.

It would also be great if the Forest Service and NRCS would work alongside state agencies to focus on species cited in the state’s Wildlife Action Plan. I think this would be a great place for multiple stakeholders to come in and work together to put strategic conservation on the ground.

Do you know someone “In the Arena” who should be featured here? Email info@trcp.org for a questionnaire.

The key to understanding the threat of CWD is learning more about the particles that cause it

My home in Wisconsin is less than 20 miles away from the detection site of the first case of Chronic Wasting Disease east of the Mississippi River in 2002. Michigan State University, where I attend school, is within the same proximity of the first detected case in the state of Michigan. It is safe to say that this disease has been in my backyard for most of my life.

As the disease spreads across the country, more and more hunters are finding CWD in their backyards, too. And while its name is increasingly familiar among sportsmen and women, CWD still remains a source of confusion for many.

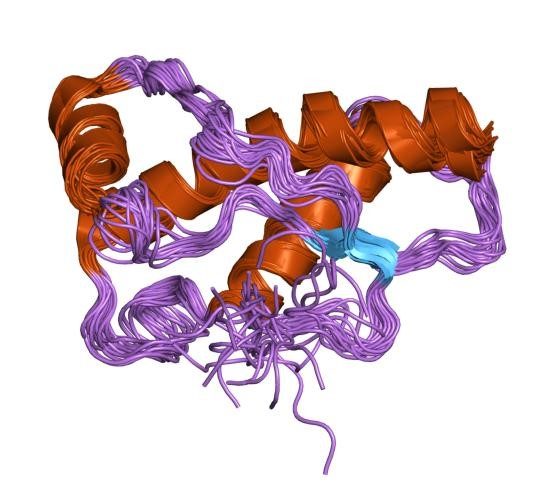

Much of this confusion pertains to the small particles that cause it, known as prions. Although we commonly associate transmissible diseases with viruses and bacteria, prions are neither. Nor are they Fungi. They are not even alive.

So just what are these things, how do they spread, and why should we be worried about them?

The term “prion” is derived from “proteinaceous infectious particle,” and it was coined in 1982 by Stanley B. Prusiner of the University Of California San Francisco. In the United States, it is commonly pronounced PREE-on, while in the U.K. it is usually said PRY-on.

In short, prions are malformed proteins. Like other proteins, they are made up of complex chains of amino acids and exist in the membranes of many normal cells. Many forms of prions are not harmful, but certain prions can be highly destructive when they accumulate in the brain or other nervous tissues of an organism.

As prions do not have their own genetic information, they cannot reproduce independently, like bacteria, or through a host cell, like a virus. Prion molecules are dangerous because they “reproduce” by denaturing the normal proteins that are in close proximity to them. This process both facilitates the spread of the disease through the body and can cause the degradation of nervous tissue.

Prion-caused diseases, CWD among them, form holes in the brains of affected organisms and are known as Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies, or TSEs—a very technical name for diseases that affects the brain (Encephalo = brain; pathy = disorder) by causing nervous tissue to become porous (spongiform = sponge-like), and can be spread from one individual to another (transmissible). These neurodegenerative disorders exhibit a comparatively long incubation period, are fatal in all circumstances, and include “Mad Cow” disease in bovid species, scrapie in sheep, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

Because they are not alive, prions cannot be killed. The collection of amino acid molecules comprising a prion must be chemically denatured to lose their detrimental capabilities. As a result, prions are incredibly resilient to change–exposure of up to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit will not deform the proteins—and can remain in a given environment for long periods of time.

In a deer infected with the disease, prions may be found in diverse body fluids and tissues, but particularly those relating to the nervous system. Bodily contact, urine, feces, and saliva can all serve as transmission vectors. In addition, a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison suggests that prions can also be present in and spread through environmental vectors, including soil columns and waterways.

It is important to consider the epidemiology of CWD when comparing it to other threats against whitetail herds. Due to the nature of this disease, it can take years of prion buildup for a deer to exhibit symptoms of CWD such as weight loss, stumbling, lethargy, and other neurological conditions, whereas viral diseases like EHD (Epizootic hemorrhagic disease) can be evident after only seven days. This is one reason why hunters do not often find heaps of deer carcasses in the field from CWD, but see mass die-offs from EHD more often. However, this does not mean that CWD is not harmful. In fact, this feature makes CWD more insidious because it is more difficult to detect early infections.

While there has never been a recorded case of cervid-human transmission, the Center for Disease Control advises against eating meat from infected individuals. As early as 1997, the World Health Organization recommended that known agents of prion diseases be kept out of the food chain. Recent research suggests that CWD could be transmissible to primates, but this has only been studied on Cynomolgus Macaques and was a single, limited study.

The nature of this disease, especially the rapid transmission and longevity of prions, makes CWD the biggest threat to herds of whitetail, mule deer, elk, and moose populations. If hunters and conservationists hope to successfully combat this disease, it will be important to support wildlife professionals and scientists in their research efforts to learn more about prions and how to appropriately address their effect.

Take action to support better research and testing for CWD across the country.

This was originally posted July 13, 2018 and has been updated.

Theodore Roosevelt’s experiences hunting and fishing certainly fueled his passion for conservation, but it seems that a passion for coffee may have powered his mornings. In fact, Roosevelt’s son once said that his father’s coffee cup was “more in the nature of a bathtub.” TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to bring together his two loves: a strong morning brew and a dedication to conservation. With your purchase, you’ll not only enjoy waking up to the rich aroma of this bolder roast—you’ll be supporting the important work of preserving hunting and fishing opportunities for all.

$4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue their efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More