The key to understanding the threat of CWD is learning more about the particles that cause it

My home in Wisconsin is less than 20 miles away from the detection site of the first case of Chronic Wasting Disease east of the Mississippi River in 2002. Michigan State University, where I attend school, is within the same proximity of the first detected case in the state of Michigan. It is safe to say that this disease has been in my backyard for most of my life.

As the disease spreads across the country, more and more hunters are finding CWD in their backyards, too. And while its name is increasingly familiar among sportsmen and women, CWD still remains a source of confusion for many.

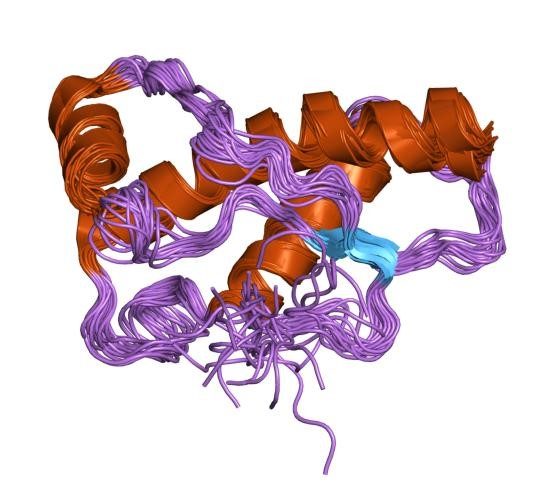

Much of this confusion pertains to the small particles that cause it, known as prions. Although we commonly associate transmissible diseases with viruses and bacteria, prions are neither. Nor are they Fungi. They are not even alive.

So just what are these things, how do they spread, and why should we be worried about them?

Prions 101

The term “prion” is derived from “proteinaceous infectious particle,” and it was coined in 1982 by Stanley B. Prusiner of the University Of California San Francisco. In the United States, it is commonly pronounced PREE-on, while in the U.K. it is usually said PRY-on.

In short, prions are malformed proteins. Like other proteins, they are made up of complex chains of amino acids and exist in the membranes of many normal cells. Many forms of prions are not harmful, but certain prions can be highly destructive when they accumulate in the brain or other nervous tissues of an organism.

As prions do not have their own genetic information, they cannot reproduce independently, like bacteria, or through a host cell, like a virus. Prion molecules are dangerous because they “reproduce” by denaturing the normal proteins that are in close proximity to them. This process both facilitates the spread of the disease through the body and can cause the degradation of nervous tissue.

[Jump to: These Changes Are Worth Your Time to Stop the Spread of Chronic Wasting Disease]

How CWD Kills

Prion-caused diseases, CWD among them, form holes in the brains of affected organisms and are known as Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies, or TSEs—a very technical name for diseases that affects the brain (Encephalo = brain; pathy = disorder) by causing nervous tissue to become porous (spongiform = sponge-like), and can be spread from one individual to another (transmissible). These neurodegenerative disorders exhibit a comparatively long incubation period, are fatal in all circumstances, and include “Mad Cow” disease in bovid species, scrapie in sheep, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

Because they are not alive, prions cannot be killed. The collection of amino acid molecules comprising a prion must be chemically denatured to lose their detrimental capabilities. As a result, prions are incredibly resilient to change–exposure of up to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit will not deform the proteins—and can remain in a given environment for long periods of time.

In a deer infected with the disease, prions may be found in diverse body fluids and tissues, but particularly those relating to the nervous system. Bodily contact, urine, feces, and saliva can all serve as transmission vectors. In addition, a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison suggests that prions can also be present in and spread through environmental vectors, including soil columns and waterways.

[Jump to: Experts Respond to Chronic Wasting Disease Skeptics]

The Big Picture Threat

It is important to consider the epidemiology of CWD when comparing it to other threats against whitetail herds. Due to the nature of this disease, it can take years of prion buildup for a deer to exhibit symptoms of CWD such as weight loss, stumbling, lethargy, and other neurological conditions, whereas viral diseases like EHD (Epizootic hemorrhagic disease) can be evident after only seven days. This is one reason why hunters do not often find heaps of deer carcasses in the field from CWD, but see mass die-offs from EHD more often. However, this does not mean that CWD is not harmful. In fact, this feature makes CWD more insidious because it is more difficult to detect early infections.

While there has never been a recorded case of cervid-human transmission, the Center for Disease Control advises against eating meat from infected individuals. As early as 1997, the World Health Organization recommended that known agents of prion diseases be kept out of the food chain. Recent research suggests that CWD could be transmissible to primates, but this has only been studied on Cynomolgus Macaques and was a single, limited study.

The nature of this disease, especially the rapid transmission and longevity of prions, makes CWD the biggest threat to herds of whitetail, mule deer, elk, and moose populations. If hunters and conservationists hope to successfully combat this disease, it will be important to support wildlife professionals and scientists in their research efforts to learn more about prions and how to appropriately address their effect.

Take action to support better research and testing for CWD across the country.

This was originally posted July 13, 2018 and has been updated.

Yeah, years ago in the 1990’s I was performing timber survey’s in Public Forest the Apache/Sitgreaves N.F., and I was close to a cow-elk and she was kinda’ spinning herself in cicles and shaking her head. She was concerned for me and my close proximity to her but not too much. That was when I first was introduced to this CWD. Thanks for your informative research report you provided, ya’ll do excellent work.

UNLESS STATES REQUIRE CWD CHECKS ON ALL HARVESTED, FARM RAISED, OR ON PRESERVES ETC. CWD WILL NOT EVEN BE SLOWED DOWN. I STILL CAN’T BELIEVE COLORADO DOES NOT REQUIRE CHECKS ON ALL HARVESTED ELK AND DEER. SEEMS TO ME THEY HAVE NOT HELPED MUCH AT ALL TO CURTAIL THIS DISEASE!

Sounds as though it would be extremely difficult to eliminate these denatured proteins from the environment. I suspect the answer more logically involves finding a way to make the affected cervids “immune” from the effects of the prion much the same as humans (currently) are. And much better if that immunity could then be passed along to offspring of immune parents. I may not be a fan of genetic manipulation but it may have a place here. C’mon whiz kids put my college tuition money to use.

”Bodily contact, urine, feces, and saliva can all serve as transmission vectors.”

Maybe deer should be dispersed from areas of high contact and concentration.

Like every federal refuge where hunting is not allowed.

My concern is if a hunter harvests a deer with CWD and it appears healthy, he consumes the deer, is this a danger to to his health? Is there any danger to consuming a deer that has just come in contact with these prions? Will this lead to no one wanting to hunt deer?

Wolves are the natural cure for CWD infections. They can detect affected deer long before the disease is evident to humans. Where there are wolves the herds remain healthy.

Yes but the prions will pass unscathed through the digestive system of the wolf and come out in their scat. This will available in the forage for the cervids.

I served on a citizen panel in Montana this past year-your info is very good, but for further info check ojut Montana FWP site for more info and ways to prevent infection in the field,