Rigs to Reefs 2-Credit Guy Harvey

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

TRCP’s new Oregon Field Representative, Tristan Henry, looks back on a recent chukar hunt and forward to the work that must be done to safeguard this iconic landscape

While reminiscing about a recent chukar hunt in the Owyhee Canyons and my new role as the Oregon field representative for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, I was reminded of a quote penned by Walt Whitman almost 150 years ago:

“As to scenery, while I know the standard claim is that Yosemite, Niagara Falls, the Upper Yellowstone, and the like afford the greatest natural shows, I am not so sure but the prairies and plains, while less stunning at first sight, last longer, fill the esthetic sense fuller, precede all the rest, and make North America’s characteristic landscape.”

I’d have to agree with old Walt. I’ve been lucky to spend many days in the field chasing chukar, hunting mule deer, and throwing dry flies and streamers across the vast expanse of public lands that constitute southeast Oregon’s Owyhee country. It’s a rare treat to sip coffee with a bird dog by your side around a morning fire as you watch the first burst of sunlight rise above the Owyhee plateau. Out there, in sagebrush-covered solitude, it can be tempting to want to save the last best places for ourselves, but sharing it is something far more powerful.

In late October of last year, I joined a group of hunters and photographers for a few days to camp, hunt, and capture images and stories about this remote and beautiful canyon country. A few in our group were lucky enough to experience the Owyhee for the first time: Sav Sankaran of the Orvis company and Durell Smith of the Sporting Life Notebook had loaded their truck more than 2000 miles away and drove 31 hours for their first shots at wild chukar with renowned outdoors photographer Brian Grossenbacher there to capture the moment. Conservation staff and local members of the Owyhee Sportsmen and their families rounded out our camp, and I can say with a great deal of confidence I would share a fire with all of them any day.

We camped in as stunning a desert campsite as I have ever seen. At the confluence of several streams, mallards circled, redband trout finned, and after a frigid night, we woke to cowboy coffee and the sound of chukar greeting the sun from the rimrocks. We discussed our strategy for the morning hunt with scalding bacon that hardened quickly in the morning cold. After the dogs were collared, we drove out of the canyon in the direction of those distant “chucking” partridge. Shutting the tailgate, I heeled my dog, beeped his collar, and began walking westward through sage and rimrock.

“It’s a rare treat to sip coffee with a bird dog by your side around a morning fire as you watch the first burst of sunlight rise above the Owyhee plateau.”

Sturgil, my 4-year-old wirehair, and I had shared some incredible days in the early weeks of Oregon’s upland season, and though this one started out a mess, we ended on a string of high notes. Birds were plentiful and I walked back to the truck with a heavy vest and one sequence etched proudly in my mind: A productive point, the approach, and a cloud of sixes finding a bird.

After a particularly wet spring brought much needed moisture to the thirsty high desert of the northern great basin, it was easy to see glimmers of that once-healthy rangeland. The weight in my vest was tangible proof of the productivity of the place, but thousands of acres of cheatgrass, medusahead, Russian thistle, and knapweed remind us just how much more needs to be done to protect the Owyhee.

Back at camp, we exchanged stories of the day over bourbon and under a star-filled sky. With a shared love for birds, bird dogs, and a thirst for community in wild places, we traversed our memories, each ridge and valley telling a story of survival and adaptation. As hunters, I suppose we’re used to navigating the thin margin between abundance and austerity, and we may be uniquely experienced in finding hope where others see desolation. There’s proof enough of that in the photos. These moments captured the stark magic of the Owyhee just about perfectly.

So few places in the U.S. offer such a complete escape from the hustle and bustle of daily life that one can truly lose oneself in nature. Fewer still offer all this splendor while also supporting grazing, hunting, fishing, and a myriad of other multiple-use purposes, but the Owyhee does. As a lifelong Oregonian and hunter, I’ve come to understand that safeguarding such places is not just an environmental imperative: it’s a moral one. It is our duty to ensure that future generations can experience the same sense of connection and awe that we find while walking in on a point.

Learn more about the Owyhee Sportsmen and how you can help protect the Owyhee Country HERE.

And learn more about TRCP’s work in the Pacific Northwest HERE.

Photo credit: Brian Grossenbacher

When you think of the Everglades, you probably think of water.

Of airboats and alligators, miles of submerged sawgrass and cypress domes. Of swamps filled with mosquitos and invasive pythons. If you’re a saltwater angler, your mind might also wander to the amazing tarpon, snapper, snook, and myriad marine fish that benefit from Everglades conservation efforts.

What may not come to mind is dry land – and the hunting opportunities those thousands of acres provide.

“It’s more than just bugs and swamps and reptiles down here,” says Richard Martinez, a lifelong outdoor enthusiast and Gladesman. “Hunting the Everglades uplands is like nothing else in the country.”

South Florida is a well-known destination for Osceola turkey hunts. But Martinez, a diehard turkey hunter who’s been a guest on MeatEater and The Hunting Public podcast, also seeks public-land deer, wild hog, ducks, and small game. This is largely due to a network of not only wetlands and waterways but also a mosaic of upland pine islands and hardwood hammocks that game species rely on for bedding, foraging, and nesting.

“In other parts of the country, you typically have to travel hundreds or thousands of feet in elevation to experience changes in habitat types, but here the ecology can change within a few inches or feet,” says Martinez.

“I find it very humbling. It’s not a very human-friendly place.”

Click here to support critical Everglades habitat protection –

A Backcountry Hunters & Anglers volunteer since 2018, Martinez currently serves on the Florida chapter’s board as chair. He helps coordinate initiatives and outreach across the state, and advocates on behalf of local sportsmen and sportswomen on habitat and access issues affecting South Florida. A strong hunting community exists in South Florida, including conservation associations and airboat and duck hunting clubs.

The Everglades are the largest subtropical wilderness in the country. And for Martinez the biggest draw of hunting in the Everglades is exploring their sheer wildness.

“I find it very humbling,” he says. “It’s not a very human-friendly place. I often feel like everything around me is telling me to go home when I’m there.”

Foreboding as it is, Everglades hunting means not just opportunities for Osceolas, migratory waterfowl, and non-migratory mottled ducks and black-bellied whistlers that are hard to find anywhere else, but an abundance of wildlife in a place that can test even the most seasoned outdoorsperson.

Martinez recalls one close encounter with a Florida panther (he’s had several confrontations with the big cats) while turkey hunting. He was on foot, traversing a “buggy trail” – Everglades parlance for offroad vehicle trails made for the region’s raised 4WD vehicles. “I came around a trail and was within 10 yards of a full-grown male panther. He bolted, but I nearly crapped my pants,” he laughs. “You don’t realize how big they are until you see them in real life.”

Like most other hunters and anglers, Martinez supports Everglades conservation efforts, but wants to make sure that hunters’ voices – in addition to the voices of anglers and conservationists – are being heard, whether looking at panther protections or determining conservation pathways to undo decades of damage from drainage canals and levees.

“Basically, half the Everglades are gone. The same amount of water remains, even though the land capable of holding onto that water is greatly diminished,” he says.

The problem is the need to put those water inputs somewhere for the land to reabsorb and filter out pollutants before they reach the ocean. Martinez says an overlooked result of human-manipulated water levels is negative impacts on hunting and habitat. “There’s a lot of push to put more water into certain interior areas that traditionally don’t hold as much water,” he says. “Those plant communities are now changing and not supporting game species like deer and turkey as well.”

Habitats found in slightly higher uplands which require little to no long-term inundation can be affected by water storage and release decisions that provide beneficial water treatment but keep plant communities submerged for extended periods. Martinez’s hunting community, alongside the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and various conservation groups tackling the challenge of Everglades restoration, recognizes the complexities of trying to undo decades of destruction and neglect.

“We shouldn’t call it Everglades restoration. It’s really Everglades reinvention. And who gets to decide how we do this?”

Thanks to the advocacy of hunters, anglers, and conservationists, the Everglades remain a destination location for the adventure-seeking archer or fowler. But out-of-staters oft come unprepared, deceived by heavily edited online videos of the easiest, most successful hunts.

Martinez offers a few tips for those who want to plan an Everglades expedition. The first is to not bite off more than you can chew; to realize how hot and inaccessible the southernmost tip of the nation can be.

“You’re gonna have a real hard time adapting to bow season in August in South Florida,” he says. First-timers should consider a late-winter or spring hunt, perhaps for hogs or turkeys in March, when the weather is cooler and water levels have receded. Or go for mid-winter snipe, which Martinez says are “probably wing shooting’s best kept secret” in the Everglades. If you only have two or three field days to spare, and plan to be on public land, it’s also probably best to seek a local guide.

Above all, if you head down to the Glades be sure to temper your expectations. “Don’t come to check a box and easily find success,” Martinez says. “Just come down for the experience.”

(Note: A version of this story also appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Backcountry Journal.)

Click here to support Everglades habitat conservation efforts by insisting that lawmakers continue to provide funding for critical infrastructure work.

Also check out our November 2023 blog on Ryan Nitz hunting barefoot in the Everglades.

Photo credits: All images courtesy of Richard Martinez

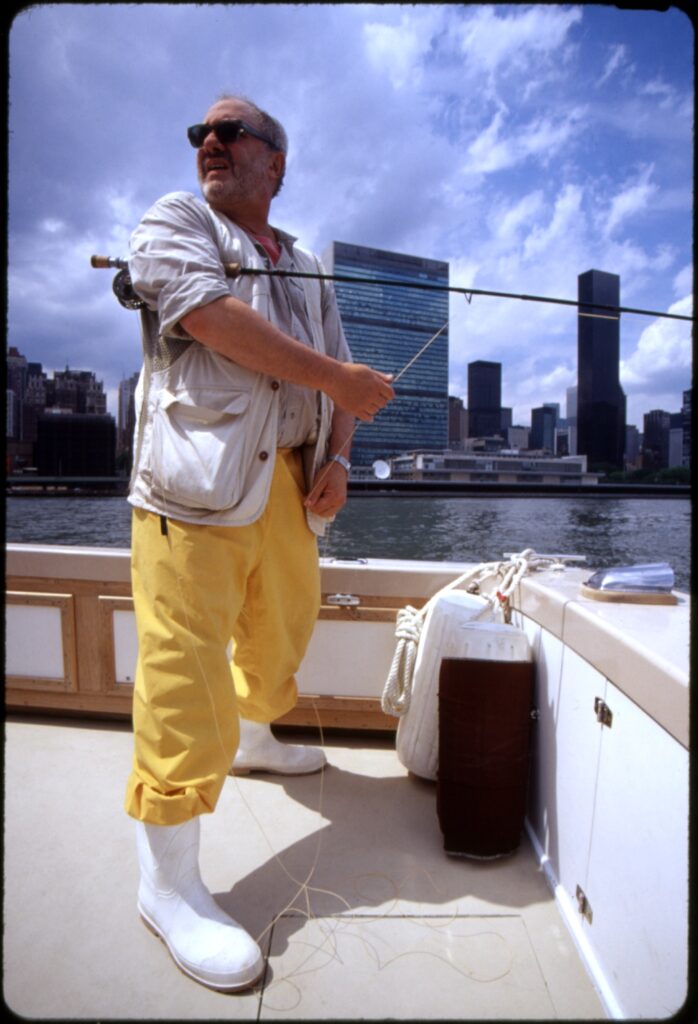

Striped bass aficionado Peter Kaminsky wrote the Outdoors column for the New York Times for 35 years. He’s also been a contributing editor to Field & Stream, Sports Afield, and Outdoor Life. A long-time flyfisher, his books include the well-known The Moon Pulled Up An Acre of Bass and The Catch of a Lifetime: Moments of Flyfishing Glory, released in 2023, which is a collection of original flyfishing essays by talented writers asked to describe their greatest angling memory. Based in Brooklyn, N.Y., he spent decades fishing Montauk’s shores and New York City waters.

Recently, he talked to TRCP about striped bass.

TRCP: Flyfishing for striped bass is one of your passions. What’s special about these fish in particular?

Peter: One of the things that was always eye opening about striped bass was there was excellent fishing right where I live in New York City. When you dial into a blitz, it brings out the hunting instinct that we are all born with. You feel as madly wild as the gulls and gannets.

TRCP: What’s one of your most memorable experiences fishing for stripers?

Peter: If we are fortunate, between Thanksgiving and the 10th or 11th of December, if we haven’t had a big Nor’easter and a hurricane then migration patterns for baitfish [on Long Island] are inshore and the fishing can be great, if it isn’t too freezing cold. This has happened only two or three times over the last 30 years. There was one year that [striper fishing legend] Paul Dixon called and said, “If you’re ever going to come, come now.” Bait was pouring out of a cut in Southampton and there were big bass. One day we just caught big fish, forty inch plus, until we didn’t want to catch anymore.

TRCP: How has fishing for stripers changed over the years?

Peter: Well, like all species, you’ll have upticks and downturns. I have seen it go from terrible in the ‘80s to great in the ‘90s, then a sort of a roller coaster up and down since. There is an element of that simply being the way nature is. But at the same time, the degrading of the Chesapeake fishery—the major nursery for striped bass—and the unrealistically generous catch limits for recreational fishing have hurt the fishery.

TRCP: Recent stock projections for Atlantic striped bass were worse than expected, which could lead to tighter fishing regulations. Is it because anglers are still getting into nice fish that they can’t believe populations are declining?

Peter: The truth is, recruitment in recent year classes is doing quite poorly. When you have really good seasons like this past one, with big fish, you tend to think it’s going to be that way forever. But if we don’t put realistic limits on keeping fish, and nothing is done to preserve traditional spawning and nursing areas for striped bass, you’re deluding yourself if you think this sort of plentiful angling will continue.

TRCP: Do you think more fishing regulation is necessary for striped bass, or more regulation of associated fisheries, such as the menhaden reduction fishery in the Chesapeake Bay—which accounts for 70 to 90 percent of the Atlantic striped bass stock?

Peter: Well, I don’t think we should be netting millions of menhaden for cat food, that’s for sure. Just as clearly, we need to mount a broad-ranging effort at recovery of Chesapeake Bay and other estuaries along the East Coast. From what I understand, it’s the recreational fishery, not the commercial fishery, that’s affecting striped bass numbers the most. This includes high mortality of fish that are caught and held out of the water too long or improperly released. I think the “Keep Fish Wet” movement is a pretty good idea.

TRCP: Stripers are targeted both because of the fight they offer and because they make great table fare. Should harvest-minded anglers currently be keeping that slot-size fish, although legal, in light of the current striper situation?

Peter: For years, I’ve always kept a striper a year as sort of a sacramental meal, but I’m not sure I will do that anymore. Or I will at least put that sacrament on hold until the bass are out of danger. They are delicious, but catching them is even more of a pleasure. You can’t have your bass and eat them too, I guess.

TRCP: Anglers increasingly seem to pursue striped bass for the chance to post their prize photo to social media. Do you post pictures of the fish you land?

Peter: In the last year, I think I took a picture of one fish. And afterward I thought, Man, I shouldn’t have done that. You get caught up in the moment. I know how it feels, but holding up fish for photos is a habit people need to break, particularly for catch-and-release anglers. We live in a selfie culture that makes it hard not to take that grip and grin. I get it. But does the world really need another picture of you and a fish? You’ve got the memory and I guarantee it’s better than any picture.

TRCP: What is your advice to other recreational anglers who want to ensure striped bass are around for future generations?

Peter: In 1983, I made a film with Jack Hemingway [Ernest Hemingway’s eldest son]. Speaking from his experience as Idaho’s fish and game commissioner, I have always remembered him saying, “I’m not saying killing fish is immoral, but if you want to preserve the fishery, then you need to value it more than the next meal. That’s the only way it’s going to work.” My best advice right now is that all striped bass belong back in the water.

Click here to read more about proposed striped bass management changes.

Lawmakers have introduced a bill to improve outdoor recreation facilities at U.S. Army Corps of Engineers managed areas.

The Lake Access Keeping Economies Strong (LAKES) Act has been introduced by Representatives Westerman (R-AR.), Womack (R-AR), and Huffman (D-CA.). Paired with the Senate version of the bill sponsored by Senators Heinrich (D-N.M.) and Cramer (R-N.D.), it seeks to better equip the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to meet the increased demand for outdoor recreation access while simultaneously growing the economic footprint of the outdoor industry in communities across the United States.

The LAKES Act would:

“The prioritization of public recreation access and the outdoor economy is a win for local communities and sportsmen and sportswomen alike,” said Becky Humphries, CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “We applaud Representatives Westerman, Womack, and Huffman and Senators Heinrich and Cramer for their leadership on the LAKES Act. It is much-needed legislation that will bolster local economies by providing more resources to outdoor recreation through improved public access, climate resiliency, and infrastructure.”

In 2022, the outdoor recreation economy generated $1.1 trillion in gross economic output and supported over 5 million jobs across the nation. Activities such as boating, fishing, and hiking thrived and increased their contributions to the overall outdoor recreation economy by 22 percent. The LAKES Act aims to address this surge in participation by empowering the USACE to provide more resources to invest in the infrastructure, public access, and climate resilience necessary to sustain continued outdoor recreation on Corps of Engineers-managed land and water.

The LAKES Act is supported by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, American Sportfishing Association, Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, Public Lands Alliance, International Game Fish Association, and more.

TRCP works to maintain and strengthen the future of hunting and fishing by uniting and amplifying our partners’ voices in conserving and restoring wildlife populations and their habitat as challenges continue to evolve.

Learn more about TRCP’s commitment to the future of hunting and fishing access here

Theodore Roosevelt’s experiences hunting and fishing certainly fueled his passion for conservation, but it seems that a passion for coffee may have powered his mornings. In fact, Roosevelt’s son once said that his father’s coffee cup was “more in the nature of a bathtub.” TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to bring together his two loves: a strong morning brew and a dedication to conservation. With your purchase, you’ll not only enjoy waking up to the rich aroma of this bolder roast—you’ll be supporting the important work of preserving hunting and fishing opportunities for all.

$4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue their efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More