TRCP’s “In the Arena” series highlights the individual voices of hunters and anglers who, as Theodore Roosevelt so famously said, strive valiantly in the worthy cause of conservation

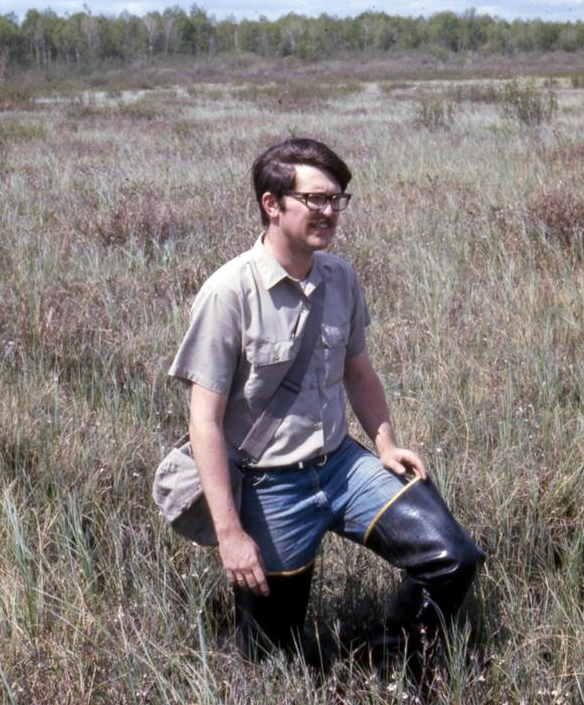

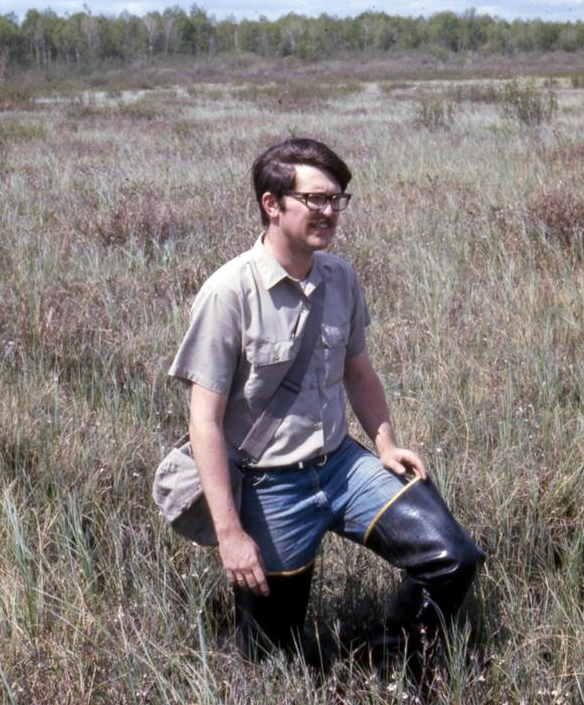

W. Alan Wentz

Hometown: Germantown, Tennessee

Occupation: Retired. Chief conservation officer for Ducks Unlimited from 1991 to 2010.

Conservation credentials: Recent winner of the Aldo Leopold Memorial Award, a lifelong wildlife management professional, and a former TRCP Board member.

Growing up in Ohio, Alan Wentz inherited from his family and community a fascination with fish and wildlife that gave shape to his private and professional life. After earning several degrees en route to a doctorate in wildlife management from the University of Michigan, Wentz spent the following decades working on conservation policy at the state and national level. A former president of the Wildlife Society, he recently received the Aldo Leopold Memorial Award, the highest honor given annually by that organization to an individual who has made significant contributions to the field of wildlife.

Here is his story.

Early Influences

My younger brother and I were both introduced to hunting and fishing by our father, who wanted to be sure we knew how to handle firearms. Like many others of that generation, his experiences in WWII led him to ensure that his children had outdoor skills. And a long association with the Boy Scouts—including serving on camp staff for more than a decade—gave me a grounded understanding of nature, camping, archery, hiking, firearms, and more.

I was also lucky enough to have several hunting and fishing mentors in our neighborhood, including one who taught me about trapping and another who was a fur buyer. The lady who lived next door was retired and took me fishing all over the county. A classmate’s father, who operated his own outdoor shop selling mostly fishing gear in a converted garage, taught me about tying flies.

More than anything else in my life, I have been most interested in conservation and the outdoors. Even as a child I was allowed to wander around the fields and woodlots near our farmstead. Observing the plants and animals and how people interact with the outdoors has always fascinated me. I devoured anything I could find in our local library on hunting, fishing, trapping, conservation, forestry, or any related topics, and enjoyed reading outdoor magazines such as Fur, Fish, and Game.

It kept me busy at all hours.

From the time I met the local game warden, I knew I was destined to work in conservation. This was in spite of my high school counselors, who laughed off the idea, and my adviser as an undergraduate at Ohio State University. After initially being surprised that I tried to declare a major in conservation as a first-term freshman, he made me pass a special written test to show him I was serious. He finally understood that I really meant to build a career for myself in conservation. I never wavered from that idea, and it seems to have worked out well.

A Life Outdoors

Two of my fondest memories from the outdoors both took place with family. The first was on one of our several trips to canoe and fish on a string of wilderness lakes in Ontario during the early 1960s. We caught several large northern pike, and my brother hooked and nearly landed a very large fish that has no doubt grown larger every time we have told the story—it was a real monster!

The second was when my brother introduced me to turkey hunting in Virginia. He called in a beautiful bird that we were able to watch coming through the woods. It was wary and circled us seemingly unsure of what we were. I tracked the bird with my shotgun for what seemed like hours (but was likely only minutes) and finally shot it.

It had looked like a large black barrel rolling down the hillside toward us, and I was so fascinated by it and the experience that I almost forgot to pull the trigger! My brother said the suspense was almost more than he could stand! It made me an addict for turkey hunting, and I’ve indulged for several decades.

Over the years, I’ve been fortunate enough to have hunted all sorts of game across North America, from Canada to Mexico and coast to coast, as well as overseas from New Zealand to Sweden. But of all the available opportunities, waterfowl hunting in eastern South Dakota or upland bird hunting on the prairies of Kansas hold a special attraction for me.

There is nothing like hunting the wind-swept prairies and public lands of our Great Plains, a landscape that I find endlessly fascinating. It can feel isolated and pristine and game can be abundant, even today and in spite of agricultural conversion and energy development. You can discover masses of upland game birds in these places and face weather that will literally steal your breath with the wind, cold, ice and snow, and blazing sun.

It is a truly remarkable experience to bend down to accept a prairie chicken from the mouth of your own Labrador retriever or to witness a 150-inch whitetail buck stand up and run away after you nearly stepped on it without knowing it was there. The abundance of life on the prairies seems almost a contradiction given how barren it can appear nearly any time of the year.

The Road Ahead

Looking to the future, we face plenty of conservation challenges, foremost among them getting people to understand that climate change is on us and that it is going to affect every aspect of our lives. These changes are going to mean major modifications to all natural resources and how humans depend on them for survival.

The general public tends to be extraordinarily ignorant of wildlife, conservation, and the base of natural wealth that sustains us all. I doubt we can overcome that ignorance and get people to accept that they must change how they live. It is the challenge of the future and one we must win.

I believe the TRCP fills a unique niche in conservation, and its outlook and philosophy is sorely needed to help us organize all the other groups that have more specific missions, while also trying to organize unaffiliated sportsmen and women. The community of outdoor groups is diverse and splintered with lots of opinions and goals. TRCP is there to help them and others understand what is at risk if we continue to talk to ourselves—or, worse yet, fight silly internal battles that are unimportant in the big picture.

With conservation facing some of its toughest challenges in our history, we have to make our conservation missions relevant and known to decision makers, young people, and voters across all nations before it is too late. There is precious little time left, and this vision must be brought to light for all to see and act upon.

An additional item I appreciate about the TRCP is the focus on access. I have been lucky enough for most of my life to be able to access both public and private lands without too much worry. However I have developed a neuro-muscular problem that has left me in a power wheelchair, and access is now a critical issue for me. It has made me aware of how many people face similar challenges.

Hopefully, access issues will be a focus of public agencies and other groups, which will greatly benefit many sportsmen and women across the country.

Top photo by Dale Humburg.