A TRCP-led workshop brings biologists, planners, and engineers together to resolve a massive obstacle to big game migration—our roads and highways

With a spectacular sunset hanging over the Nebraska prairie, I loaded my chocolate labs into the truck at the end of a great afternoon of sharptail grouse hunting. It had been the perfect rest stop to break up a long drive, while also yielding some exercise, a limit of birds, and another memory in the field. But it was time to get moving.

Pulling off a deeply rutted dirt road onto pavement, I accelerated to the speed limit—or thereabouts— set my cruise control, and settled in.

And then it happened. Before I could pump the brakes, flash the lights, or honk the horn, I was on top of a small herd of mule deer with only enough time to grab the steering wheel tight and brace for the inevitable impact. Once the vehicle slowed to a stop, I spun the truck around and returned to where my vehicle had struck one of the does.

I’ve walked up on many big game animals taken while hunting, usually with a strong mix of emotions, and always grateful. But as I approached the dead deer on the side of the highway, I only felt regret for what seemed like a useless loss of life.

An All Too Frequent and Costly Scenario

I suspect nearly every sportsman or woman has a story—or several—about collisions and near misses with wildlife on roads and highways. According to the Highway Loss Data Institute, drivers filed more than 1.8 million animal-strike claims, mostly involving deer, at an average cost of about $3,000 each between 2014 and 2017. That’s a more than $5.4-billion cost to insurance companies alone in just four years.

These accidents also cost state transportation and wildlife agencies dearly in time, resources, and other expenses. Rural states like South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming, which have high rates of vehicle-wildlife collisions, spend upwards of tens of millions of dollars annually responding to wildlife-vehicle collisions.

But this issue goes beyond safety hazards, loss of human and animal life, property damage, and other economic costs.

Can Deer Even Cross the Road?

Roads and highways are pervasive features across landscapes where they never used to be. By their very nature, they break up habitat into fragments and have the potential to severely disrupt animal migrations. The numerous interstate highways that cross our nation north to south and east to west present major obstacles for animals trying to move from one area to another to reach seasonal habitat and winter range.

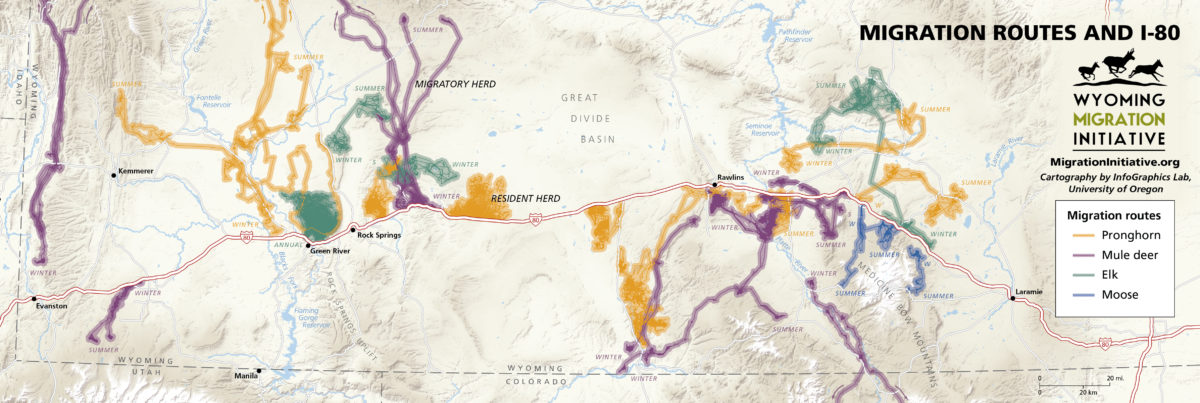

Maps overlaid with GPS-collar data show quite clearly how abruptly migrations halt in cases where animals reach an interstate highway. Data from several studies compiled by the Wyoming Migration Initiative indicates that I-80 in southern Wyoming serves as a significant barrier to movement for pronghorn antelope, mule deer, and elk. Likewise in Arizona, biologists have identified a 31-mile segment of I-17 as a hotspot for collisions and a movement barrier for migrating elk.

Fortunately, there are solutions in the form of structural crossings that allow animals to move either over or under the highway, and ample scientific evidence illustrates their effectiveness. More than 20 years ago, the Canadian government installed six overpasses and 38 underpasses along the Trans-Canada Highway, long recognized as a barrier for big game and other wildlife. Now, it’s considered an international conservation success story—these efforts reduced vehicle-wildlife collisions by 80 percent.

Many states across the U.S. have enjoyed similar results from installing over- and underpasses along major highways. Wyoming’s Trapper’s Point on Highway 191 and Highway 9 in Colorado are good examples of how effective this approach can be. Still, there are many places where wildlife-vehicle collisions and barriers to movement remain a problem for human safety and the conservation of our big game herds.

© 2018 University of Wyoming and University of Oregon).

Bridging the Gap

When former Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke signed an Order to improve habitat quality in big game winter range and migration corridors—a policy lauded by sportsmen and women—the Department asked the 11 Western states covered by the policy to submit their top three to five priority project sites for mule deer, elk, or pronghorns to be worked into collaborative action plans. Significantly, highway crossings ranked among the top priorities for every state. Some even called out multiple roadways—all five of Idaho’s priority projects involved highways and issues with animal movement and collisions.

That’s why DOI asked the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership to organize a gathering of experts and decision-makers to discuss how we can get more wildlife crossings where they are most needed.

More than 80 participants from 11 state wildlife agencies, 12 state departments of transportation, three federal agencies, and several NGOs and foundations gathered in Salt Lake City in late January. We discussed the differences in how wildlife agencies and DOTs operate, lessons learned from past efforts, assessed what policies currently exist, and identified partnership, funding and policy needs to address the issue.

Collaboration Will Be Key

While Wyoming, Colorado, and Montana had held similar workshops at the state level, never before had professionals from multiple states gathered together to discuss highways and big game migration and collisions to learn from one another’s successes and failures. And this collaborative aspect was key for the success of the event. We wanted to foster connections across state agencies and among stakeholders, identify best practices and key points of leverage for action, and advance the states’ priorities under the Secretarial Order on migration.

It became clear that engineers with state DOTs—the talented people who build and maintain roads, bridges, and other structures to allow the movement of vehicles safely and efficiently from point A to B—and biologists need to work better together. Monte Aldridge from the Utah DOT summed up this lesson very simply, advising wildlife managers to “get to know an engineer.”

Another takeaway was that wildlife and personnel from a state DOT and wildlife agency personnel need to communicate early and often, with an eye towards solutions that allow all parties to achieve their goals. In the past, by the time wildlife professionals engaged in the planning process and identified the need for an under- or overpass, it might have been too late.

And, of course, all participants recognized that there is never enough money to go around. Ideas were exchanged about how NGOs, foundations, private landowners, and other entities can partner with federal agencies to help state wildlife agencies and DOTs successfully fund and maintain wildlife highway projects.

The Worst Thing We Can Do Is Nothing

Utah DOT Executive Director Carlos Braceras gave voice to the spirit of the workshop by quoting Theodore Roosevelt and telling the crowd that “the best thing we can do is the right thing, the second-best thing we can do is the wrong thing, and the worst thing we can do is nothing.” He encouraged the group to share not only their successes but also their challenges, pitfalls, and mistakes so that others can learn from them.

The work ahead is really where the proverbial rubber will hit the road, not only for the state-identified priority projects, but also for the many areas across the country where wildlife and transportation conflicts need attention. This workshop was one step toward helping to ensure our wildlife conservation and transportation needs can be integrated, and the lessons learned should help with the larger efforts down the road.

Among other things, this gathering illustrated the role that the sporting community must continue to play as a partner with our state and federal agencies and other stakeholders to address wildlife-transportation conflicts. The solutions, while expensive and not easily planned or installed on a whim, are well-studied and proven. But we need to encourage the support and political will of agency leads and decision-makers to help keep the momentum rolling.

Top photo: Gregory Nickerson/Wyoming Migration Initiative

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes’ Wildlife Management Program has been working cooperatively with the Montana DOT on lessening wildlife vehicle collisions on the Flathead Indian Reservation for the past nearly twenty years, through wildlife crossings, fencing and other designs. We continue that work and are now working to lessen grizzly bear road mortalities through cooperative planning, design and construction.

As a civil engineer and dedicated sportsman, it is great to see these crossings implemented across the landscape. My family was also affected when a deer came through the windshield of our truck on the interstate in NE and my pregnant wife took the brunt of the deers impact while myself and two daughters struggled with the ensueing catastrophe. Luckily we all made it out alive.

These crossings not only save wildlife but will save human lives as well. The safe and continued passage of these wildlife on their anecestral migrations are crucial for the natural balance of herds to thrive and survive.

This group meeting holds the best hope for wildlife that need our support. Let’s get this done for our children and grandchildren.

Oregon Hunters Association was successful in getting wildlife underpasses and fencing on US 97, it bisects a migration route that wildlife must cross twice a year to survive. It has reduced wildlife collisions by 90%. There is another section that Highway Division will build bridge but will not fund fence. So far we have over $400,000 pledged to build, still need more.

I learned a lot. Canada seems to have developed action that works.

Highways and roadways are major barriers to the movements of large wildlife such as deer; but they are much more serious, often nearly impassable barriers for smaller wildlife such as reptiles or amphibians, small mammals, and non-flying arthropods. Snakes for example are unable to move quickly over pavement, where their usual locomotory techniques find little traction, and are killed in staggering numbers without attracting much attention. People who run over snakes at highway speeds are usually not even aware of the event, and the flattened remains of a dead snake are soon crushed into a nearly unrecognizable blob on the pavement. Even more than for larger wildlife species, roadways are for the smaller wildlife a formidable barrier to free movement and thus a severe obstacle to the genetic “diffusion” necessary, as we now know, to the long-term genetic health and even survival of almost any animal population. We are aware of collisions with larger and iconic animal species, not least because humans may suffer property damage, injury or even death in such collisions; but the impact on the less conspicuous but far more numerous smaller members of the ecosystem is much less obvious – and in my estimation even more important. I am aware of a few “toad crossing” projects, but I suspect it is still easier to obtain funding for a deer underpass than for a technically far more difficult migration corridor for let’s say dragonflies – some of which perform astounding mass migrations and are sometimes killed by the thousands when they cross busy vehicle traffic.

We are still, I think, far too oblivious of the nature and gravity of our “ecological footprint”.

I’ve always thought that the only dumb animal in the woods is the one with two legs. The same holds true on the highway. This being said, I beleive that the drivers will come to depend on these crossings and become even less vigilant on our roadways.

For three years, we’ve reached out to the broader community in central Oregon giving fact based information on the urgent need for more wildlife crossings across Highway 97, an historic migratory corridor that is fast becoming a barrier for Mule deer. The response is nearly 100% positive in supporting habitat connectivity. The larger community is a great resource to enlist in support for more wildlife crossings and protection of winter range. The message is, that this is a community concern and responsibility to join in collaboration with public agencies and NGO’s.

Glad to see Ed and TRCP involved in this issue; the Hwy 9 project here in Colorado creates a great template on how the surrounding community, including both private and public partners, can work together for wildlife and human safety. I would love to see a crossing be put in along the I-70 corridor due not only to the fact that the Eisenhower tunnel provides the only natural land bridge for wildlife along the I-70 corridor for many, many miles but also due to the visibility and education value such a project would have with the millions of motorists that utilize this road throughout the year.