PA stream Joanna Gilkeson / USFWS

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

Veteran Lafitte speckled trout and redfish guide Maurice d’Aquin took a break from cutting sheetrock and clearing debris from his house in early August 2021 to have a look at what Hurricane Ida had done to some of his favorite fishing spots.

What he found stunned and upset him almost as much as the three feet of mud left by Ida he was trying to shovel and till in his yard.

“I went to a shoreline on the west end of Little Lake, a spot where I had caught nice redfish all spring and summer and it was completely gone,” d’Aquin said. “I went to the exact mark on my GPS where I was casting to redfish along a shoreline and had to go across about 700 yards of open water before my trolling motor even touched mud.”

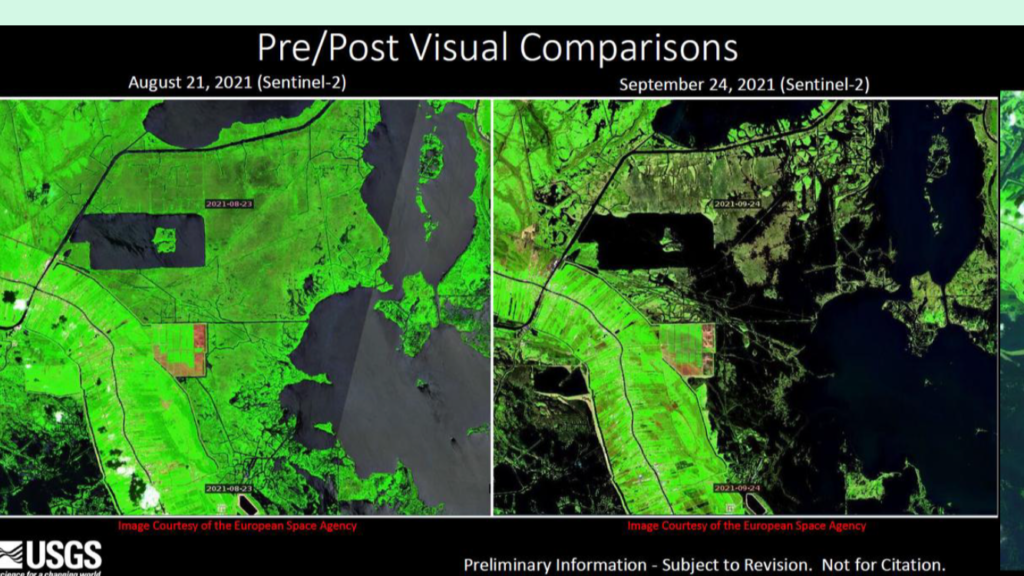

What d’Aquin has found by boat across the upper reaches of Barataria Bay, especially on the western and northern stretches of Little Lake, has been confirmed with both aerial surveys by Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority and satellite images gathered by the United States Geological Survey. Hurricane Ida’s 150 mile per hour-plus winds scoured and decimated Louisiana’s coastal marshes in ways not seen since Hurricane Katrina removed an estimated 200 square miles in 2005.

The Extent of the Damage

Early indications are 106 square miles of marshes washed away or were displaced by Ida’s savage winds and 10-foot storm surge. The destruction spreads across areas of Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parish east of the Mississippi River all the way west through Terrebonne Parish.

The Barataria Basin bore the brunt of Ida’s fury. Marshes west and south of Empire in lower Plaquemines and Jefferson Parish that never recovered from Katrina were decimated again by Ida, taking what little was left in areas closer to the Gulf of Mexico and damaging recently restored barrier islands. It’s the extensive damage in the northern reaches of the Barataria system, however, that has coastal wetlands experts and fisheries biologists most concerned.

“The whole Barataria Basin is only about 700 square miles, so to lose about 100 of those in one event like Hurricane Ida is significant and stunning,” said Brian Lezina, Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority’s Chief of Planning. “There’s a chance some of it will come back. The marsh can heal itself in time if the resources are there and vegetation regrows. But we won’t know how much will recover for a few years.”

Lezina said much of the marsh damage was in areas where organic materials and lighter silt make up the soils. Some of it was flotant, which is marsh that roots in decaying vegetation floating above the organic soils beneath. Ida scattered the uprooted marshes and light, organic mud, filling in nearby canals and fouling Lake Salvador and Cataouatche and shoving mud and grass into and under houses from upper Plaquemines Parish west into Jefferson and Lafourche. Organic soil marshes and flotant are much more susceptible to wave action and erosion than marshes east of the Mississippi River and those closer to the mouth of the Atchafalaya River, which receive annual sediment deposits of heavier clays and sand. They also lack the ability to repair themselves in the same way as areas that get sediment replenished annually by the rivers.

Resources to repair the marsh are often hard to come by in areas far removed from the river and the sediments it carries. Lezina said the CPRA and federal partners are evaluating the best options to try to repair some of the damage. He’s optimistic some regeneration will occur through a combination of natural processes and dredging projects.

“You have the Davis Pond Diversion nearby and the Intracoastal Canal that both can carry some water and sediment into the badly-damaged areas,” he said. “The sediments are being reworked all the time by waves and current. If the submerged vegetation grows back in shallow areas, it can help capture some of that sediment. And we’re looking closely at what resources can be directed into the area to help recapture some of the sediment.”

A Fishery Transformed

Chris Schieble, a marine fisheries biologist with Louisiana’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, said the exact long-term effects of the dramatic marsh losses from Ida on fisheries production are hard to predict. However, as more organic soils and marsh “edge” are lost to storms, daily wave action and sinking of the land below the water line called “subsidence” that is eating away at the Barataria and other basins across Louisiana, fisheries production is certain to decline.

“It’s the organic materials and rotting vegetation called detritus that feeds the food chain in areas that don’t get a lot of sediment and freshwater input from the Mississippi River,” Schieble said. “Areas where the fresh and saltwater mix more east of the river and near the Atchafalaya River, the food chain starts with phytoplankton. But in organic soils, the ones that look like coffee grounds, it’s the nutrient leeching out of the soil that makes up the base, feeds the forage fish, and ultimately the predators like speckled trout and redfish.”

In the short term, marsh loss from storms can cause an increase in fisheries production and lead to more catches of speckled trout and redfish as fish orient to newly created and exposed edge habitats, shallow flats and washouts where tidal flows concentrate baitfish.

D’Aquin said he’s seen that firsthand in areas damaged by Ida.

“The storm opened up some new cuts along the shoreline in Lake Salvador where water is flowing in from the Intracoastal Waterway,” he said. “We caught a lot of redfish in the early fall in those washouts.”

In the long-term, however, the profound loss of marsh and organic materials will inevitably lead to a decline in fisheries production as nutrient levels drop and vital nursery grounds for juvenile shrimp, crabs, mullet, and other forage is lost. Lezina and Schieble both said the Barataria Basin and other areas hardest hit by wetland loss over the last century will reach a tipping point where the benefits of new edge habitat created by storms will be outweighed by the habitat and nutrient loss and the conversion to open water.

“We may already be at that tipping point in the Barataria Basin,” Schieble said. “If you look at the time of year when Ida hit, it’s a time where we would be seeing redfish larvae recruit into the marsh and white shrimp developing in those marshes. The redfish might have been displaced or not recruited into that marsh at all. Ida’s path and destruction couldn’t have been worse for our recreational and commercial fisheries. Productivity and access have taken a big hit.”

Anglers Adapt, Look to the Future

The extreme changes in habitat have also altered where anglers and guides have had to focus their efforts since the storm. Many guides and recreational fishermen have also noted a change in the size and number of fish they’ve been catching.

Captain Joe DiMarco has been fishing east and west of the Mississippi River out of Buras for more than three decades. He said the habitat loss and the fishing on the east side of the river is far different than what he’s seeing west of the river after Ida.

“The east side didn’t take nearly the beating we are seeing to the west where a lot of the smaller cane islands and humps where we caught trout last year are now gone,” DiMarco said. “We see some damage on the east side on the edge of Black Bay, but nothing like on the west. The storm seems to have pushed in a lot of big redfish too. Seems like we are catching many more 27- to 35-inch redfish way up in the marsh than we are 16- to 27-inch fish.”

D’Aquin said he’s having to relearn to fish his home waters around Lafitte in the same way he did after Katrina 16 years ago.

“Canals where we caught speckled trout during the winter are almost completely filled in and islands and peninsulas where we were catching trout and reds in the past are gone,” he said. “Just like after Katrina, we are seeing fish that are stressed and we are having to make adjustments. The fish and the marsh suffered just like the communities hit by the storm. But just like the communities are coming back slowly so are the fish. Each day gets a little bit better.”

As you may have seen, the TRCP partnered with Steven Rinella and Janis Putelis at MeatEater to educate deer hunters on an important step they can take to prevent the spread of chronic wasting disease—deboning your deer in the field. We recently got a great question from a hunter who wants to do the right thing and prevent bringing home the soft tissues that may contain CWD, but also wants to maximize their harvest. So, we called on a highly respected wildlife disease specialist to provide an answer.

Tune into the video or read on below for more.

Question: If you want to use them yourself and are not transporting the animal out of state, is it still safe and legal to use the bones to make tools and bone broth? I don’t like the idea of wasting so much of the carcass.

Wildlife disease ecologist and New York deer hunter Krysten Schuler answers:

As a hunter, I understand why you’d want to get the most you can out of your harvest. Many states do not allow hunters to bring whole deer carcasses home from another state. They typically ask that the harvest is deboned, because CWD prions exist in a variety of tissues, so it’s easiest just to have hunters bring back edible or trophy portions that most people want to keep and leave the rest behind. Disposing of these parts so they end up in a landfill, instead of on the landscape, is really the best method for hunters to avoid creating a new CWD hotspot in the woods.

There was a lot of debate among wildlife professionals about whether quartering would be sufficient vs deboning. The concern was that the larger bones, which you’d likely use for stock or making tools, would be thrown out on the landscape if a full deboning was required. In the end, it was a judgement call to minimize the risk and also help with language clarity, as people may have different ideas about which bones could be retained while quartering.

The bottom line: If you’re not moving your harvest from one hunting zone to another, it is perfectly legal to use the bones for stock. But if you hunt in a CWD zone, I’d get my deer tested first—the CDC recommends that no one knowingly consume a CWD-positive animal. This goes for all parts. Cooking or boiling won’t “kill” CWD prions.

Do you have more questions about CWD? Check out this blog from our archives, where three CWD experts respond to the most common gripes we see from CWD skeptics.

Find the latest opportunities to get involved in advocating for CWD solutions here.

The Department of Interior’s recent decision to cancel two hardrock mineral leases on public lands upstream of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness was widely supported by hunters and anglers. It was also in line with an agency process supported by our community. But this is just the first step toward permanent protection of these essential resources. Here’s what you need to know about what comes next.

First, a quick review of what’s at stake: The Boundary Waters, the most visited Wilderness Area in the country, is made up of more than 1,100 lakes and 2,000 designated overnight campsites all connected by rivers, streams, and portage trails along Minnesota’s northern border. The 1.1-million-acre Wilderness Area lies within the Superior National Forest, the largest contiguous forest in the eastern region of the United States.

The waters within hold high quality habitat for walleyes, smallmouth bass, northern pike, and lake trout. In the face of a changing climate, the area offers some of the clearest, coldest, and deepest waters in all of the boreal forest open to the public for fishing, camping, and hunting. Ruffed grouse, whitetail deer, moose, and migratory birds also frequent the lakes and rivers in and around the BWCAW, an area directly adjacent to Canada’s 1.2-million-acre Quetico Provincial Park and in the same watershed as Minnesota’s 220,000-acre Voyageurs National Park.

Last week, the Biden Administration decided to mitigate some of the threats to these resources by canceling two federal mineral leases upstream of the Boundary Waters. This rectified a process that would have endangered habitat and outdoor recreation access downstream. The action was in keeping with the science-based, public-facing approach we have advocated for since 2018, when the TRCP and its partners called on federal agencies and decision-makers for a “stop and study” approach to this new type of mining in the region.

But future leases could be considered unless Congress passes legislation to permanently protect the Boundary Waters. Further, there is still a need for more evaluation of the environmental impacts of hardrock mining, especially if we hope to put this idea—and the risks to fish and wildlife—to rest for good.

This is why federal agencies are currently completing a study that could put a moratorium on any new hardrock leasing in 225,378 acres of the surrounding watershed of the BWCAW, putting that acreage off-limits, as well. While the study is underway, the Bureau of Land Management has initiated a two-year segregation of new federal mineral leases within the proposed withdrawal area.

Importantly, during a 90-day comment period concluded on January 19, 2022, sportsmen and sportswomen overwhelmingly urged federal agencies to take action to protect the watershed of the BWCAW. Thousands of business owners, hunters, anglers, and countless others in the outdoor community spoke in favor of the withdrawal because tourism and jobs in the local outdoor-recreation-based economy depend on the Boundary Waters.

There will be other opportunities for the public to weigh in as the study progresses, and at the conclusion we hope to see federal agencies commit to a 20-year moratorium of new hardrock mineral leasing in that area of the Superior National Forest. The Boundary Waters is a unique landscape and critical part of the American Wilderness system that is deserving of permanent protection from water pollution and impacts to habitat and access downstream. Federal agencies have the discretion to set the study area aside from new leasing for up to 20 years after gathering public input and scientific data that inform such a decision.

In the end, the Boundary Waters can only be permanently protected from this type of mining by H.R. 2794, the Boundary Waters Wilderness Protection and Pollution Prevention Act. After the current moratorium ends and federal agencies enact a longer-term mineral withdrawal order, an act of Congress must be signed into law to permanently declare the area off-limits from future hardrock mineral leasing. This would permanently reinforce the decision by federal agencies to set the 225,000-acre area of the Superior National Forest aside from this kind of leasing for up to a 20-year period.

The legislation has been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives by Representative Betty McCollum (D-Minn.). Federal agencies have begun to right past agency decisions to renew hardrock mining leases in the watershed, and it is up to elected officials to seal the deal and secure this critical habitat and bucket-list paddling, fishing, and hunting destination for future generations.

Learn more and sign up for updates on this issue at SportsmenBWCA.org.

Spencer Shaver is the conservation director for Sportsmen for the Boundary Waters . He is a lifelong hunter and fisherman, a graduate of the University of Minnesota’s environmental science, policy, and management program, and has guided Boundary Waters canoe trips since 2014.

Photos by Hansi Johnson. Follow him @hansski43 on Instagram.

Here’s how Wyoming hunters and anglers can raise their voices during the legislative session this month

On February 14th, Wyoming’s citizen legislature will convene in Cheyenne for its biannual budget session and this year is a particularly important one for hunters and anglers. Included in the proposed budget is a $75 million dollar allocation to the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resources Trust. If funded, it will provide payouts to critical conservation projects across the state for decades to come. Along with other soon to be introduced bills affecting Wyoming’s wildlife, the fate of WWNRT funding is an important opportunity for hunters and anglers to make sure their voices are heard this year in Cheyenne.

That’s why we’re excited to partner with the Wyoming Wildlife Federation, Bowhunters of Wyoming, and the Wyoming Wild Sheep Foundation for this year’s Camo at the Capitol event on Thursday, February 24th. This FREE all day advocacy training is an opportunity for Wyoming hunters, anglers, and wildlife enthusiasts to gain the tools they need to effectively lobby elected representatives and make lasting policy change to the benefit of our shared wildlife heritage. After a morning training and included lunch, participants will tour the capital, lobby legislators and finish out the day with a Sportsmen’s legislative reception featuring Wyoming wild game fare and drinks on us!

As the least populated state in the country, we have closer access to our legislators than we might think in Wyoming. It’s time for us to use this opportunity to speak up for the wild places and wildlife of this great state, I hope you can join us later this month.

Josh Metten

Wyoming Community Partnerships Coordinator

Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership

Photo: @joshmettenphoto

TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to further our commitment to conservation. $4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue our efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More

Sign up below to help us guarantee all Americans quality places to hunt and fish. Become a TRCP member today.

For every $1 million invested in conservation efforts 17.4 jobs are created. As Congress drafts infrastructure legislation, let's urge lawmakers to put Americans back to work by building more resilient communities, restoring habitat, and sustainably managing our water resources.