Levees built right on the riverbank were once the golden standard for preventing dangerous flooding, but setting structures back from the river could help communities faced with increasingly costly storms, while improving habitat

As common flood protection structures, earthen levees line American rivers and streams. Levees constructed in response to historic river flooding—where property damage soared and life loss steadily increased—have been relied upon for generations.

But these manmade barriers also work against our natural environment. Connectivity of a river to its floodplain is critical for the exchange of flows with the river, which deposit and transport sediment through the watershed and support the sustainability of fish and wildlife populations. Levee construction across our major river systems has interrupted and prevented this natural and beneficial ecological function of floodplains.

Over time, Congress acknowledged the adverse impacts of human development that depletes habitat by passing the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970 and the Endangered Species Act in 1973, among other legislation. But levees are still used today. Fortunately, there is a way to make communities more resilient from flooding and reconnect habitat that relies on life-giving sediment and river flows.

It’s Not a Question of Whether Levees are Good or Bad

Numerous levees have performed and continue to perform as they were originally intended. Just ask someone from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. For that matter, just ask me. After 34 years of service with the Corps, I’ve seen the good and the bad associated with levees.

On the one hand, levees have prevented devastating flooding from occurring in large cities and small towns—protecting critical facilities (like hospitals, fire and ambulance stations, utility distribution services, government buildings, and military bases) as well as acres upon acres of productive farmland.

However, many of these levees were designed before we began experiencing the apparent effects of climate change, which could pose higher risks now and in the future.

A levee’s height and width will not change once it has been constructed. No matter how much you water it, that levee will not grow. The design conditions are static, with levee performance being based upon the hydrology and hydraulics from when the levee was originally designed. Unfortunately, the climate is dynamic and, as we have witnessed over the past decade, the intensity and frequency of severe weather is increasing along with the failure of vulnerable levees—most recently within the lower Missouri River Basin.

When a levee fails, the results can be catastrophic to people, buildings, infrastructure, livestock, and cropland. Setting levees back far enough to allow the river more room to convey flood waters, while protecting all landward assets, could solve multiple problems.

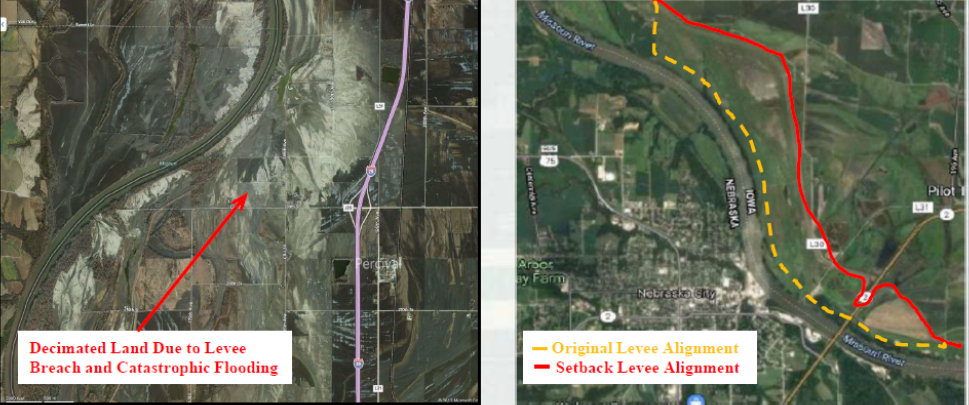

The photo on the left below illustrates the devastation to the land after a levee breach occurred along the Missouri River during the 2011 flood. The photo on the right illustrates the levee setback that was implemented after the flood, improving flood conveyance, reducing the depth of inevitable floods, and increasing the resiliency of the levee.

Further, the land located riverward of the levee has been enrolled into conservation easements, reconnecting a large portion of the historic floodplain and allowing for that critical exchange of flow between the river and the floodplain.

Environmental Benefits of Levee Setback Projects

Diversification of flood flows through reconnection of the historic floodplain to the river is the greatest environmental benefit associated with a levee setback like this one. As shown in the images below, fish and wildlife are flourishing within the conservation easements, because they mimic natural ponds and wetlands. The positive trade-off of transitioning some productive cropland to conservation easements by realigning the levee is that fewer levee failures will occur, the setback levee is more resilient to flooding, and the environment has an opportunity to recover.

Consider the Setbacks

The cost of setting a levee back from the river can be millions of dollars. The cost of not setting back certain levees, especially those that continue to encounter flood damage, may be costlier in terms of damage to buildings, infrastructure, livestock, cropland, and the environment. While funding from the federal government flows with fewer restrictions to states and local governments after a disaster, it would be beneficial for states and federal agencies to identify vulnerable levees now—prior to flooding.

We must acknowledge that our needs have changed since levees were first designed and constructed. Continuing to rebuild after every damaging flood, rather than implement forward-thinking solutions, like levee setbacks, all but guarantees that fish and wildlife habitat will continue to suffer.

Learn more about this issue and proposed solutions here.

Randall Behm is retired from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after 34 years as a professional engineer. As a consultant, he now works nationally on the implementation of nonstructural flood mitigation measures and advocates for the setback of perennially damaged levees to improve flood-risk management and environmental benefits.

Top photo by Justin Wilkens on Unsplash

Excellent article! Hope the levee setback will become the norm.

I would like to see every state and federal agency commit to a national program of moving levees back from the rivers. As is, we get some benefits from current levee construction but a national program of moving levees back with produce many more benefits than just flood control. Water quality, less flooding and erosion, and fish and wildlife benefits would be huge and pay multiple dividends. Great article.