Before smoke filled the sky this wildfire season, an unwanted invader was already crowding out wildlife food sources in sagebrush country—now, it’s burning

With more than 20 major fires and hundreds of smaller ones burning over a million and a half acres in California alone, it’s shaping up to be a long and expensive wildfire season—for people, wildlife, and habitat.

Fire can, of course, be good for forests, grasslands, and sagebrush when it keeps invading conifer trees at bay, adds nutrients to the soil, revitalizes forbs and bunchgrasses, and creates a mosaic of favorable habitat conditions. This assumes a normal ecological cycle of growth and renewal over many years.

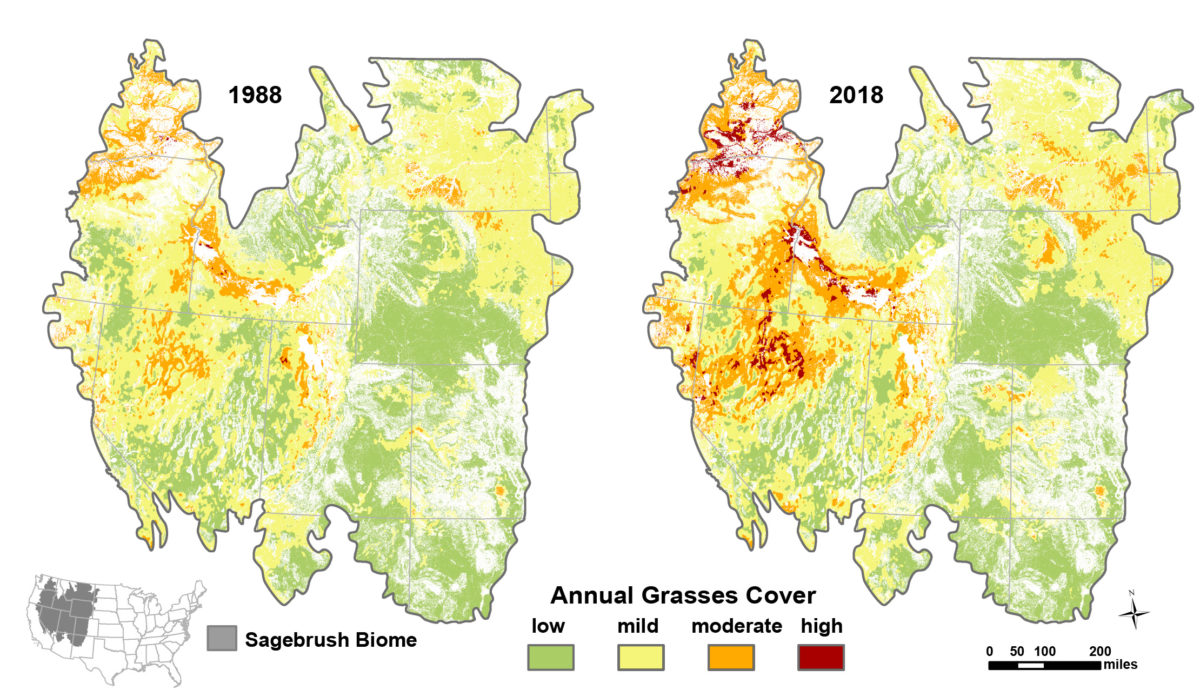

But an invasive menace has changed much of the West’s fire cycle, especially across the sagebrush sea, damaging the very habitat that supports more than 350 species of plants and animals, including sage grouse.

That menace is cheatgrass, and it represents one of the greatest threats to this uniquely Western landscape. Here’s why.

The Grassy Villain That’s Winning the West

While there are many non-native plants that have spread across the country, none rival the destructive impact of cheatgrass.

Though it’s an annual species—meaning that it lives for just one growing season and then dies—cheatgrass produces enormous amounts of seed that remain viable for many years and germinate quickly under the right conditions. Cheatgrass spreads easily by wind but is also carried by a wide range of mammals that get its barbed seeds stuck in their fur. This is also how the seeds travel on a hiker or hunter’s boots and socks!

From there, cheatgrass can quickly and efficiently dominate disturbed areas of bare ground.

Native to parts of Europe, southwestern Asia, and northern Africa, cheatgrass was first discovered here in New York and Pennsylvania in 1861. By the late 1920s, it had spread across the country, finding especially favorable conditions in the fragile, dry shrublands of the Great Basin, Columbia River Basin, and across the Intermountain West.

This is where it has put a stranglehold on native plants important to at-risk sagebrush species, altering ecological processes and changing the way wildlife use their environment.

Cheatgrass can easily overtake a landscape and outcompete native plants, often creating vast monocultures. The grass itself has little to no value as forage or cover for wildlife, but it decimates the forage available to both wildlife and livestock, which can have serious consequences for ranching operations. And without diverse perennial forbs and bunchgrasses—those that live for more than one growing season—there is little to hold the soils together and retain moisture.

But perhaps the most pervasive impact of cheatgrass domination has been its influence on the size, intensity, and natural cycles of wildfire, especially in the sagebrush sea.

Upsetting the Balance of Nature

While large and sometimes severe wildfires historically burned in sagebrush, they were infrequent and returned only every 60 to 100 years, depending on elevation, soil moisture, and other conditions. Native forbs, grasses, and sagebrush evolved with fire and adapted to this interval between blazes. Up until just a few decades ago, wildfires usually burned less intensively and more sporadically across the landscape, thereby creating more diversity in the age and structure of sagebrush plants while maintaining the bunchgrasses and forbs that are so valuable as cover and forage for wildlife.

But that has largely changed in areas plagued by cheatgrass invasion. Cheatgrass dies just in time for a typical fire season to start and is an extremely flashy fuel—one that can turn a simple lightning strike or discarded cigarette butt into a raging inferno in minutes.

When cheatgrass dominates an area and a fire gets started, it is almost equivalent to spreading gasoline across the surrounding vegetation.

Today’s fires are becoming hotter and more frequent in part because of the dominance of cheatgrass. Hotter fires mean that more sagebrush and other native plants that are not adapted to frequent high-intensity fires will certainly be lost. The soil is damaged, which weakens the system’s ability to regenerate sagebrush and perennial forbs and bunchgrasses.

Worse yet, after a hot fire, the disturbed soils are ripe for re-invasion by—you guessed it—cheatgrass.

Scientists now estimate that fire in cheatgrass-dominated areas can return every five years or less as a result of this broad ecological change. These areas may never return to their native condition and can essentially become biological deserts. And each year, the vicious cycle continues and results in more and more sagebrush and other habitats being dominated by this invasive species.

A Different Kind of Blaze

A bird hunter is never going to pull up to a huge burned area of sagebrush and unload the dogs, but many Western big game hunters know that a few years after a fire sweeps through a landscape, these areas can become prime habitat for elk and mule deer. This is especially true for forests with so much canopy coverage that sunlight couldn’t reach the ground and regenerate vegetation that big game like to eat.

In a normal cycle of fire and regrowth, yes, this balance is restorative. But the new normal of catastrophic blazes and cheatgrass-driven fires can severely alter winter range and other big game habitats.

There is major concern about the impact of fire on the survival of sage grouse, in particular. According to the Bureau of Land Management, more than 15 million acres of sagebrush burned across the West from 2000 to 2018.

While some of those acres may have been restored naturally or with human intervention, many are now part of the perpetual and unrelenting cheatgrass-fire cycle, which does not bode well for deer, pronghorns, elk, or sage grouse.

An Ounce of Prevention

In our own lives, we know it’s cheaper and easier to take care of ourselves—eat right, stay active, and get preventative screenings—than to wait for a crisis to send us to the emergency room. The same is true of maintaining rangeland health.

Once cheatgrass takes hold of a landscape, it is extremely difficult and expensive to eradicate. The problem may be widespread at this point, but it hasn’t completely taken over all habitats in all places. Reactive measures in these areas should continue, but proactive measures to conserve and restore the resilience of native vegetation are more likely to succeed.

Fortunately, projects to prevent and remove cheatgrass invasion can create jobs at a time when many Americans are out of work. But decision-makers need to invest in these efforts to make a difference.

The cheatgrass-fire cycle is daunting, but cannot be ignored. We need more attention given to this crisis and state and federal resources to combat it. Failure to address this clear and present danger will have consequences for fish and wildlife habitat, soil health, forage diversity, and our Western economies that depend on healthy sagebrush ecosystems.

Failure to act may also mean watching our hunting and fishing opportunities go up in smoke.

Top photo by Nolan E. Preece/USFWS via flickr

Sure would have been helpful for you to have included some close-up photos of this menace at the various stages of its annual cycle…so we may identify and do battle with it. Also, more botanical information, please.

I worked as a biologist in the Columbia Basin for nearly 20 years. Any shrub-steppe community that is over grazed by livestock, will contain cheatgrass. Native song birds, who nested in cheatgrass infested habitats, ended up having to defend a larger area to procure food. In the Southwest, another species of Brome will ultimately decimate desert ecosystems. Protect pristine communities now by immediately removing all livestock. Allow grazing in habitats that have already succumbed to cheatgrass.

Great article! Moved to Montana a couple years ago and found how harmful cheat grass is so have been trying to remove it from our property by spraying, pulling and weed whacking! It’s quite a battle and we’re not winning yet but plan to keep on fighting it. Have heard they are working on a chemical that will kill it but not other grasses hoping that’s true!

Getting rid of cheat grass is a good idea as long as the treatment isn’t worse than the problem.

It would present a great opportunity for our incarcerated people. And like our boarders we need to do a lot better job of keeping these kind of things out of our country! We are having a huge issue in our area with wild parsnip, buck thorn, and honeysuckle.

So what’s the answer? Tell us ways to eradicate this horrible grass. One of the previous responses asked about the progress on a chemical spray to target cheat grass. What is the status on this?

Population control, More control of grazing in sensitive areas